Jed Distler’s podcast The Piano Maven is a terrific listen (footnote 1) and Distler’s latest episode offers ten favorite Brendel recordings.

I trust Distler, and have made a note of his choices. (Brendel is not the only mid-century giant who recorded major pieces three or four times, so it can be a bit troublesome sorting out what is what on the streaming services.)

Schubert C minor sonata the first recording on Vanguard

Mozart Concertos in D minor and C minor with Charles Mackerras and the Scottish Chamber Orchestra

Schoenberg Concerto on DG with Rafael Kubelik and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra

Liszt Totentanz with Bernard Haitink and London (I just listened to this, it’s great, never would have known about it but for Distler)

Beethoven Diabelli Variations 1988 Phillips

Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition first version for Vox

Mozart Sonata in F, K 533 from 2003, although Distler also recommends the 2008 farewell concert

Weber Sonata in A-flat

Schumann Concerto Kurt Sanderling 1998

Brahms Variations on an Original Theme

I never saw Brendel live in the 1990s, in part because his records of the core repertoire never really resonated at home. He obviously could play the music, but I did not “feel it.” Additionally, the fraught act of managing my slim finances helped keep me away from Brendel at Carnegie Hall.

While the pianist had an enormous career supported by a devoted fan base, my casual criticism was not unique. Most of the obituaries note that some connoisseurs thought that Brendel was overrated, and in fact Jed Distler himself has a complicated relationship to Brendel.

To muddy the waters further, I went through a love-hate relationship with Brendel’s copious writings on music. As a college student I was initially delighted with his first book, Musical Thoughts and Afterthoughts, but soon had an about-face where I decided that Brendel was just too high-handed and aversive.

Brendel usually starts an essay from a place of scolding: “Let me tell you why so many are wrong about this esoteric topic.” Good examples of this rhetorical gambit are found in Brendel’s first three essays on Liszt, all three written years apart, all commencing with a complaint about then-current Liszt reception. At one point Brendel tries to take the argument into Charles Rosen’s territory, decrying what Rosen says about Liszt in Rosen’s The Romantic Generation. Here I simply must put my foot down and insist that when it comes to Franz Liszt, Charles Rosen is right and Alfred Brendel is wrong. (Footnote 2.)

That said, spending the last few days poking around in the final compilation Music, Sense, and Nonsense (which includes Musical Thoughts and Afterthoughts among other more recent pieces) was undoubtedly a good use of my time, for the essays are entertaining and educational. They also clearly made an impression: With some regret, I acknowledge that Brendel is certainly an influence on whatever I try to do in my own writing.

One of the most charming chapters is “A Lifetime of Recording,” which tracks Brendel’s progress with various labels and the industry. One paragraph is a suitable coda to Distler’s list. (Footnote 3.)

In a separate essay on live recording, Brendel is particularly happy with the 1983 Beethoven concerto cycle in Chicago with James Levine conducting. I just listened to the 4th Concerto and was impressed by the tremendous amount of rhythmic flexibility in both pianist and orchestra.

There’s always more to learn. Not long ago I heard a record by Brendel that just blew me out of the water, a live performance of the Busoni Toccata in Vienna in 1979. Holy moly!

If I had heard this in the 1990s, I might have a completely different relationship to Brendel. It’s not too late, which is why I copied down the lists from Distler and Brendel himself: I want to refer to this page when revisiting the late great pianist’s recorded legacy in the future.

Ferruccio Busoni is already someone I return to with interest. To some extent his compositional output might have been too eclectic, but a singular image finally emerges in his late work, with the Toccata generally considered to be one of his best pieces. (Footnote 4.)

The Toccata is from 1921, a particularly good year for piano repertoire from all over the globe. There was not a unified idiom or message, everything was up for grabs, the assortment of masterful sounds is wildly diverse.

(Debussy, Scriabin, Reger, and Granados had not made it to the 1920s; Ravel had finished his last big piano work, Le Tombeau de Couperin, in 1917. Atonality was brand new and not widely accepted. Ragtime had landed, but just peeking through the curtain was much more jazz and pop music to come.)

Igor Stravinsky Trois mouvements de Petrouchka (1921) Stravinsky only wrote one virtuoso showcase, and many would declare it his most important piano work. I was delighted to hear an up close version from Owen Williams in an ASU practice room a couple of months ago.

Arnold Schoenberg Suite for Piano Op. 25 (1921-23) As with Trois mouvements de Petrouchka, Schoenberg’s Suite is the most popular work of this composer (at least for virtuosos). Indeed, this is surely one of the two most performed 12-tone works in all of piano history, with the comparatively easy Webern Variations being the other. The Suite is complex—naturally—but a good live performance can deliver something absolutely rarified. A few years ago I sat in the front row in a small hall while Steven Beck delivered a mesmerizing sermon of pure dissonance.

Sergei Rachmaninoff, Paraphrase of Kreisler’s Liebesleid (1921) With typical snobbery, Alfred Brendel insists that Rachmaninoff was not a genius but a grand seigneur. While I personally would have no problem calling Rachmaninoff a genius, it’s also true that some of his most famous compositions can be a bit on the nose. At any rate, I have unqualified reverence for the transcriptions. “Liebeslied” is a charming waltz by the famous violinist, and Rachmaninoff’s own recording of his marvelous transcription is one of the greatest things of all time.

Gabriel Faure, Nocturne no. 13 in B minor (1921) Faure’s last piano work starts like Bach but soon expands into a whole other universe of harmonic possibility. The substantial dimensions suggest a Ballade. Vladimir Horowitz made this one almost his own personal property.

Ferruccio Busoni Toccata “Preludio, Fantasia, Ciaccona” (1921) Two brilliant etudes surround a quasi-religious episode in Busoni’s remarkable “visionary” style. Busoni was always somewhat neoclassic, but his late work added straight triads used in a blocky and unexpected way. This harmonic grammar is elusive and “incorrect,” but it works. I’m still not used to writing this sentence, but: The best recording I’ve heard is by Alfred Brendel.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold Three Pieces from Much Ado About Nothing (1921) There is not much Richard Strauss or Gustav Mahler for the solo pianist to play; this is what we have instead, a little set not in the active repertoire, yet probably Korngold’s best solo piano piece. (The early sonatas from Korngold’s prodigy years are amazing but not quite there.) Recommended recording: Martin Jones.

Darius Milhaud Saudades do Brasil (1920-1921) This polytonal and groovy tribute to Rio de Janeiro includes Milhaud’s most popular piano pieces. The great composer William Bolcom, who also wrote many delightful ragtimes (a shared interest with Milhaud), plays the suite on an old Nonesuch LP.

Widening the frame away from 1921 by a year or two in each direction produces much more….

Charles Griffes Piano Sonata (1919) The talented American composer sadly died young in 1920. His lone sonata successfully marries a bit of Debussy and Scriabin to New World grit. I like Leonid Hambro (which also must have been one of the first recordings) but that’s hard to find. Garrick Ohlsson’s recent Griffes overview is excellent.

Carl Nielsen Suite Op. 45 (1919-20) Nielsen was not a dedicated piano composer, at least when compared to his powerful symphonic writing, but the Suite has a mysterious and elusive beauty and boasts absolutely unpredictable harmonic progressions. Recommended recording: Leif Ove Andsnes.

Leopold Godowsky, Triakontameron, (1919-1920) Godowsky wrote 30 pieces in 3/4 time covering six volumes; he claimed to have written each in a single day. All the pieces have quality, and some are genuinely interesting. I prefer certain Godowsky transcriptions and the brilliant original Java Suite, but Triakontameron is still part of a certain moment of extreme fecundity in the piano world. Godowsky himself made a piano roll of the most famous movement, “Alt-Wien.”

Nikolai Medtner Sonata-Reminiscenza (1920) Like his friend and peer Rachmanioff, Medtner was a bit out-of-step with contemporary thought. His best music has truly wonderful qualities, and the Sonata-Reminiscenza might be his most immediately charismatic larger work; the opening theme is unforgettable. Marc-André Hamelin’s recording is exceptional.

Béla Bartók Improvisations on Hungarian Peasant Songs (1920) Charles Rosen regarded Improvisations as one of Bartók’s best piano pieces; Rosen also made an excellent recording. The work is attractive but rather patchwork compared to authentic Bartók masterpieces Three Etudes (1918) or Piano Sonata (1926).

Heitor Villa-Lobos, Rudepoêma (1921-26) The largest piano work by Villa-Lobos is a real adventure, a deep percussive dive into the innards of the piano. Recommended recording: Marc-André Hamelin.

Paul Hindemith Suite 1922 (1922) In what is perhaps a minority opinion, I regard the uptempo moments from Suite 1922 as the peak of Hindemith’s piano writing. (Others would argue for the Sonatas or Ludus Tonalis.) Indeed, I’ll go a step further, and rank the suite as the best “jazzy” work from a European composer of the era. I just love the live Sviatoslav Richter recording from late in Richter’s life.

Sergei Prokofiev Two Pieces from "The Love for Three Oranges" (1922) Prokofiev’s masterful transcription of a March and Scherzo from his 1919 opera have proven to be among his most popular piano pieces. Recommended recording: Frederic Chiu.

Dmitri Shostakovich Three Fantastic Dances (1920-22) Written when just a teenager, these charming works show that the composer already had a personal style well in hand. Shostakovich clearly agreed, for he took the time to record them himself in the 1940s.

There’s surely much more, especially from composers I don’t know so well such as Poulenc, Krenek, Szymanowski, de Falla or Frank Bridge. I’d put Ruth Crawford Seeger’s gorgeous Nine Preludes in there, but since they are from 1924-1928, that is starting to feel like a little bit of a different historical moment.

Footnotes

Jed Distler notifies his Piano Maven listeners via Substack. Not long ago Distler reviewed the Debussy record of Hiroko Sasaki; Hiroko will be my duet parter on the next “classical” recording featuring my Sonata for Piano Four-Hands.

The Brendel/Rosen debate comes down to Rosen’s assertion that something like the hit Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 is central to Liszt’s identity, whereas Brendel wants the layperson to learn about the subtle harmonic innovations of the obscure Variations on "Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen." Again, Rosen is obviously right. (The discussion of Liszt in The Romantic Generation is just fabulous overall: at one point Rosen compares Art Tatum playing “Tea for Two” to Liszt taking up an opera melody, a superb and snobbery-free analogy.)

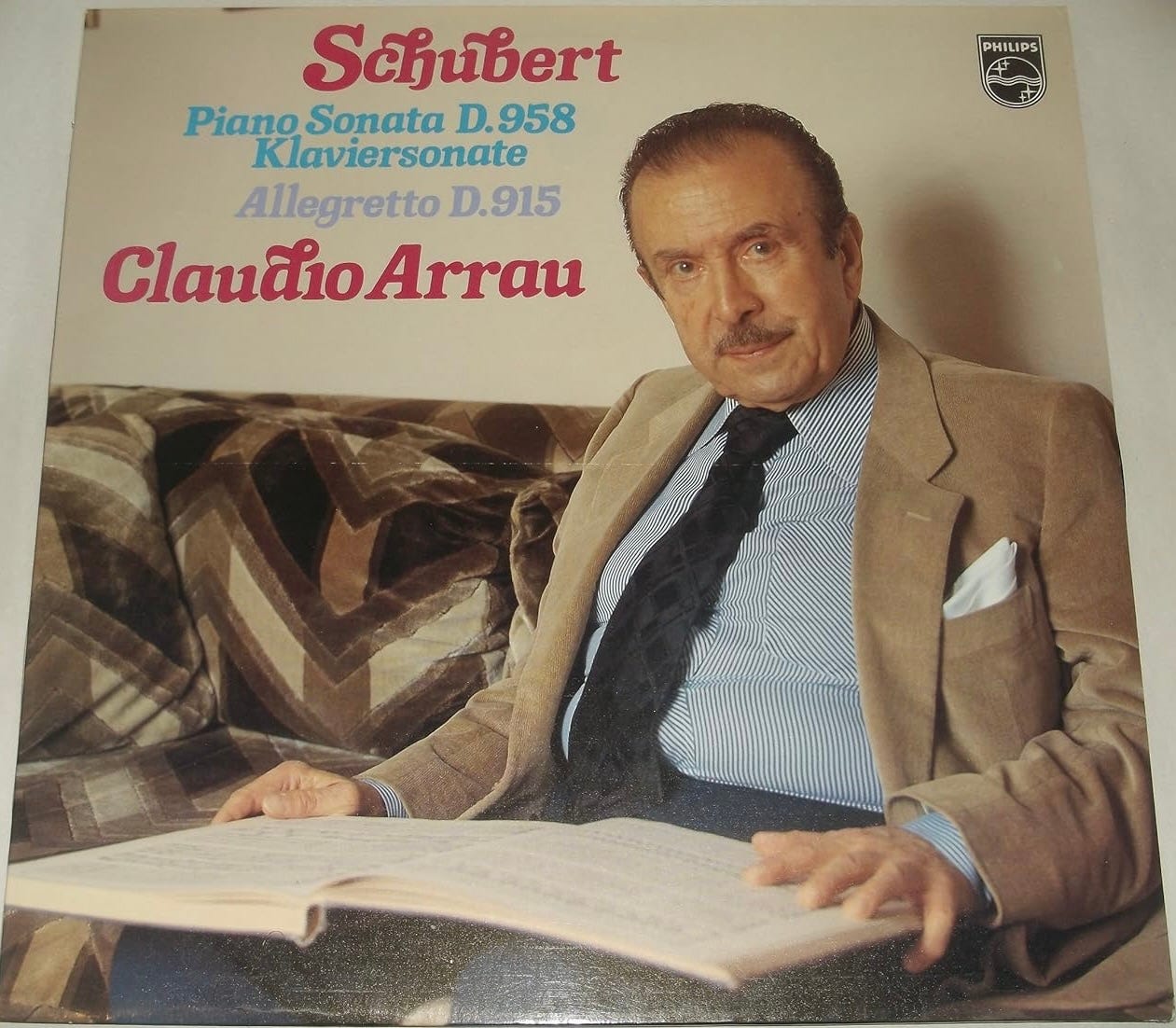

On his list of preferred records, Brendel praises his own Vallée d'Obermann. I listened. He can play this music well, but not for the first time I am left with the impression that Brendel lacks a natural melodic line. Compare stately Claudio Arrau or demonic Lazar Berman in Obermann; both can “just play the pretty tunes” in a manner that can elude Brendel.

One of Brendel’s earliest recordings was the very first traversal of Busoni’s massive Fantasia Contrappuntistica, just recently reissued in excellent sound as part of the historical Toblach Ausgabe series, a release that also includes intriguing rarities by Liszt and Richard Strauss.