TT 382: Maurizio Pollini and the End of Scarcity

farewell to an era-defining pianist, with a helpful aside from Mark Padmore

If you listen to classical piano repertoire, you’ve listened to Maurizio Pollini, one of the biggest names of his generation.

I have a favorite track, his recording of the finale of Prokofiev’s 7th piano sonata, Precipitato. Just awesome!

Pollini was a superb concerto player, and a wonderful video of the Beethoven’s Emperor with Karl Bohm and the Vienna Philharmonic boasts a spectacular opening cadenza. When players of this caliber deliver such masterclasses in efficiency and musicality, it almost seems like the piano is playing itself.

Due credit to Bohm and the members of the orchestra as well. The voice of Beethoven speaks.

David Allen’s obit in The New York Times is thoughtful and extensive [gift link]. In addition to telling Pollini’s life story, Allen goes into some detail about the Pollini controversy, as some listeners found him literal and impersonal. Allen, while a fan of the pianist, also has a good line about an “imperious new set of the Chopin Études, recast as if they were Brutalist edifices.”

This is an age-old argument in classical music. It’s not quite technique versus feeling, for all good players can deliver the notes, and all good players offer emotional performances. The nth degree of artistry is something subtle, a mixture of things that is hard to describe. Words or even intellect don’t really suit the topic. (Just today I read a sentence from Edgar Allan Poe that gestures at this problem: “By undue profundity we perplex and enfeeble thought; and it is possible to make even Venus herself vanish from the firmament by a scrutiny too sustained, too concentrated, or too direct.”)

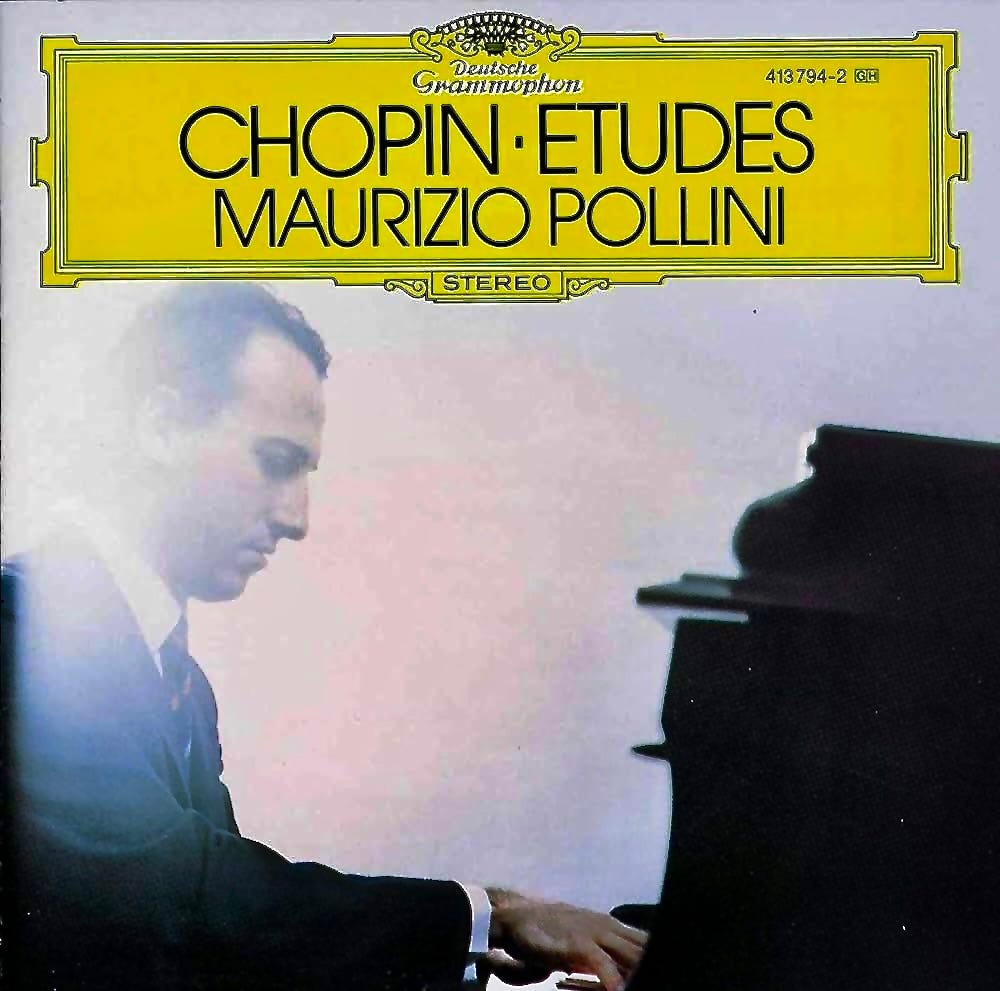

That said, if you work on the Chopin Études, you listen to Pollini’s era-defining record on Deutsche Grammophon. Of course you do. It’s fast, clean, and absolutely musical. At the time of first release in the ‘70s it was the “best.”

Allen’s comment about “Brutalist edifices” lands in part because these Chopin Études were just one of a sequence of high end DG productions. Indeed, Pollini ended up being a kind of poster boy for the great selling of the great repertoire by powerful companies at the height of their financial success. (The complete Pollini on DG takes up something like 65 hours, or 55 compact discs.)

For late-20th century critics writing articles and books supplying a list of the “best” recordings of the standard rep, Pollini on DG was an obvious go-to. You didn’t even need to listen to them, for you knew they did the job. (Just be sure to file ‘em on the shelf with the yellow DG spine clearly visible.)

That’s the sticky point: Are we actually meant to sit around with a carefully curated library of “best” performances? If there is no scarcity, is it still valuable?

In the important 2017 Guardian essay “A Passion for Bach,” Mark Padmore uses a fresh production of the St. John Passion to make some key points about this very topic:

There is something distorted – one could say, dysfunctional – in the relationship between classical music and recordings. Pretty much the entire repertoire was written for live performance – indeed most of it was written before recording was invented. Yet for many, classical music is provided by the huge catalogue of recordings instantly available on the internet.

There are, of course, many benefits to being able to access such an extraordinary resource but there are also some dangers. The first stems from the ease with which we become casually familiar with music. Like the Woody Allen joke – “I took a speed-reading course and read War and Peace in 20 minutes. It involves Russia” – we are led to believe that because we know how a piece goes, we actually know the piece. I would argue that there is always more to learn, more to discover and because music unfolds over time we can only ever hold an impression of a piece in our mind. The second danger is that we start to hear live performance passively, as if it were an aide-memoire to the unfolding of the familiar. We probably notice if something goes wrong but otherwise we can essentially allow a performance to remind us of what we think we know already. We hear, but we don’t listen.

The third danger is that our reliance on recordings encourages a strange connoisseurship whereby they are judged against one another. There is a misguided search for the definitive performance – as if there could be one single ideal interpretation. People pull out obscure vintage recordings in the way that someone might show with a vintage wine. This is where the record collection resembles the stamp collection – music becomes a possession rather than a process. The point is, we are in danger of losing touch with the greatest strength of classical music – its liveness. The unrepeatable, unpredictable nature of great music performed in the moment for that moment only.

Before the 20th century, if you wanted to get to know a piece you had to attend a live performance or get hold of a score and work through it on whatever instrument or instruments you had available. There is a wonderful chapter in Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus in which Wendell Kretzschmar leads the local community through a course on great works by Bach, Beethoven, Bruckner and Wagner. He hammers away at the piano, shouting out descriptions of the orchestration and musical structure as he goes. This gives a vivid idea of how difficult it is to get to know music – the effort involved in acquiring knowledge. Even if you lived in a city with a symphony orchestra and opera house you would hear only a handful of works in any one season. The thrill of hearing an orchestra play a Beethoven symphony you had only ever heard on a village piano would have been enormous.

Maurizo Pollini made excellent records and offered excellent performances. I’ve owned two dozen of his CDs, and saw him live twice. All of it was essentially unimpeachable…yet in the end I’m a bit of a Pollini doubter, for little of it gave me what Padmore writes above: “The unrepeatable, unpredictable nature of great music performed in the moment for that moment only.”

If all goes well, the future of Beethoven and Chopin performance will boast performers taking greater risks in front of smaller audiences eager for vulnerability and intimacy, and the luxurious production line of Pollini and Deutsche Grammophon will have been just one moment in the longer story.

There‘s a documentary of Pollini on Youtube that might be of interest. A great inside into his thinking, especially since he gave so little interviews: https://youtu.be/LMpcUEVijyE?si=rSUCOLOR_ldzirsu

You might find this comment useful, from Tim Page's Washington Post obit: “We have to live with the fact that a performance is given an artificial permanence, and that our ideas are always changing about a piece of music,” he[Pollini] told Gramophone magazine. “A record must be accepted as a document of a particular moment in time. I hardly ever listen to my old records.”

But, Ethan, your piece brings to mind other experiences and comments. A composer friend of mine after reading two reviews of a concert (not of HIS music): "They're reviewing their record collections, not the performance." (I think it was a Mahler concert.) And, given my undergraduate zeal regarding the "best" performances on record, my then-girlfriend said, "I'm not interested in Bernstein or Karjan, I'm interested in Beethoven!" .... It's also funny that comparing Page and Allen's assessments, Allen is the more Apollonian! ... And thanks for the recording tips anyway!