TT 530 part two: Richter's Diabelli Variations and Arrau's Schubert C minor sonata

(parenthetical to previous Alfred Brendel post)

Lazy Sunday (“Wake up in the late afternoon”). After publishing a fairly concise comment on the late Alfred Brendel, I've kept in the mode of listening to great classical piano music.

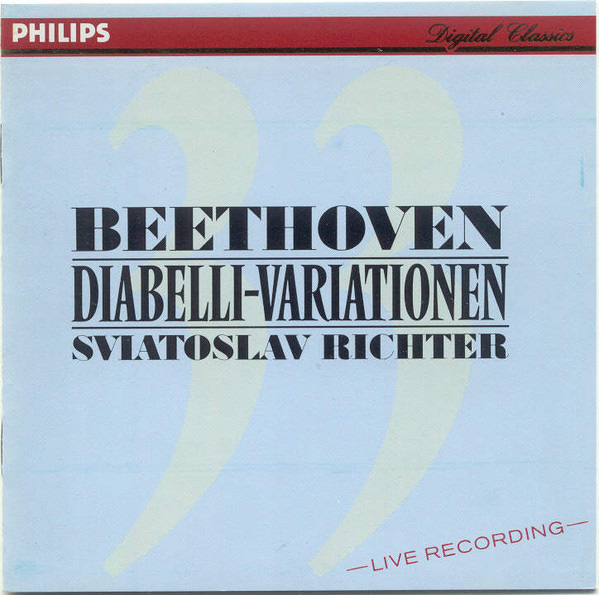

In high school I mostly cared about jazz, although the Glenn Gould recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations made an impression. My friend Eric Stassen (who knew so much more about European repertoire than me) followed up by giving me Sviatoslav Richter’s CD of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations (recorded 1986), which I listened to just as much as Gould’s Goldberg.

After I got to New York in 1991, I studied a bit with excellent classical pianist Fabio Gardenal at NYU and started buying LPs of standard repertoire on the street. Quite literally the street: There would be outdoor vendors near Waverly Place offering terrific finds for a modest price. CDs were expensive, so old LPs were the way to acquire some basic familiarity with core repertoire.

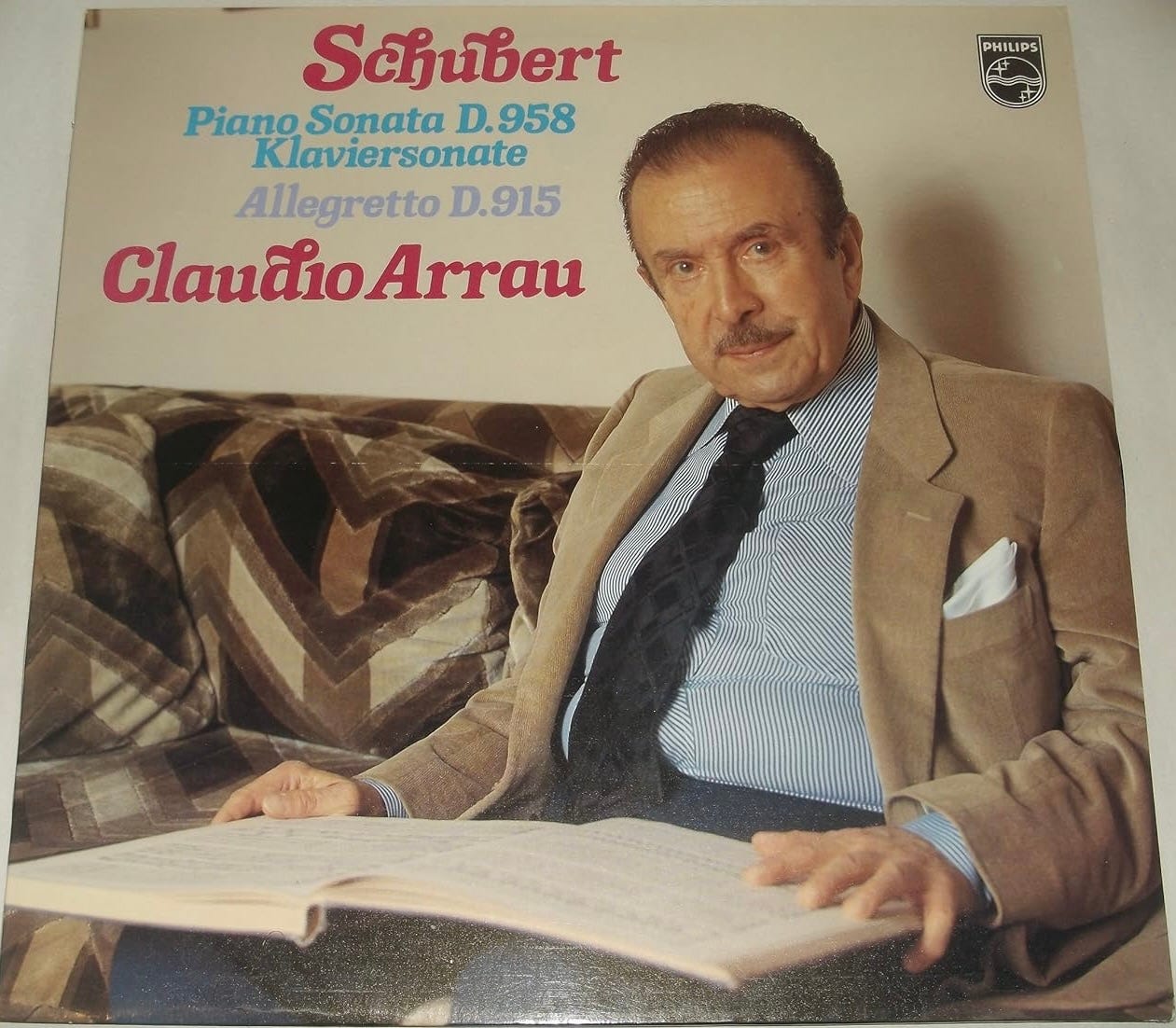

Somewhere in there I found a copy of Joseph Horowitz’s book Conversations with Arrau. While probably intended for those who already knew who Claudio Arrau was, the volume also proved to be an engaging introduction to the lore of the classical virtuoso. On Waverly Place they had Arrau’s Phillips records of Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms, and Liszt for $2 a pop. I’d buy a new LP every week and listen while reading what Arrau had to say about the repertoire.

In my experience, understanding the dimensions of pre-20th Century repertoire is not that hard. Each composer is so different. One Beethoven, two Beethoven, three Beethoven: The language then unlocks. Same for anyone else truly great in the canon. (In America this is all frequently considered a hopelessly esoteric topic, but in Europe many relatively young people still sort of “get” the great composers the way they “get” Shakespeare or Orson Welles.)

Pretty soon I had amassed a large library of recordings and scores. I couldn’t really play classical piano—Of course, I couldn’t really play jazz, either. But the cheerful pursuit of both disciplines would go on to essentially be the story of my life, an undertaking that provides me with an infinite amount of material to study, practice, and attempt to make my own.

When looking over Jed Distler’s list of top-shelf Alfred Brendel, I noticed that he cited recordings of Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations and Schubert’s C Minor sonata. I gave a quick listen, and immediately returned both stamped, “no sale.”

Part of what Brendel is up against is my own history as a listener. I have already mentioned Richter in Diabelli, while the Schubert C minor was one of my favorite Arrau LPs.

This is one of the major problems faced by all critics in any genre: How do you get away from first love? Early moments of initial contact can never be undone. Youthful passions afflict our every judgement. It’s the only real reason any of us are in this game anyway: We are still chasing that germinal intoxication.

Tabling Brendel for now, I went back and re-listened to Richter and Arrau.

The Diabelli Variations is late Beethoven, quite tough and experimental in its way. Famously Beethoven thought the proposed theme was horrible—I dunno, it’s not that bad—and proceeded to take it apart for an hour. Each variation is quite different from the next, the emotions range from bitter sarcasm to lofty transcendence. One of the strengths of Richter’s recording is how each track delivers a radically new sonic image, even though it is live record with an out-of-tune piano. Incredible piece and incredible performance.

The C minor sonata of Schubert is also a late work, one of three final sonatas. Looking back, I can see now that I liked this sonata partly because it is so clearly modeled on Beethoven (the adagio is even in A-flat) but sounds so different. Arrau tells the story directly and without fuss. I read somewhere that Arrau’s piano sound was “bronze,” a good description, although his left hand is no longer quite as even as it could be on this circa-1980 recording. (Arrau was born in 1903, and time comes for us all.)

Temperamentally Richter and Arrau inhabit different places of the beat. Richter is quicksilver, rushing into each new event with gusto, while Arrau is measured, appropriate, and secure. But both have rhythm; rhythm in a cosmic sense, rhythm in a Classical sense. When they start an Allegro there is absolutely no doubt of the organization of tempo. The phrases exist against an (unheard) ground bass.

My teacher Sophia Rosoff called it “emotional rhythm,” after Virginia Woolf, who wrote in a diary:

Style is a very simple matter: it is all rhythm. Once you get that, you can't use the wrong words. But on the other hand here am I sitting after half the morning, crammed with ideas, and visions, and so on, and can't dislodge them, for lack of the right rhythm. Now this is very profound, what rhythm is, and goes far deeper than words. A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it; and in writing (such is my present belief) one has to recapture this, and set this working (which has nothing apparently to do with words) and then, as it breaks and tumbles in the mind, it makes words to fit it. But no doubt I shall think differently next year.

I will keep listening to Alfred Brendel, and to Maurizio Pollini also. (I posted a somewhat skeptical note after Pollini’s recent passing.) They were both immensely famous but neither was ever my favorite, especially in Beethoven or Schubert. When Brendel or Pollini begin an Allegro, I just don’t always hear enough rhythm, at least compared to most Richter or Arrau. (To my mind, both Brendel and Pollini are better in Beethoven concertos than Beethoven sonatas, for the orchestra takes on so much of the essential beat.) But, following Virginia Woolf’s lead, I will keep leaving room to “think differently next year.”

Ethan, my father grew up in Germany before coming to this country in the 1920s. He was not a musician, but could pick up an instrument--piano, accordion, flute, whatever and play by ear. This is a talent which I most definitely did not inherit. Anyway, every morning at breakfast he listened to classical music when I was growing up. I was into rock and was not interested. In my late teens I got into jazz and he had no ear for it and we had arguments. I was immature and could not argue properly. He died when I was 19.

It was not until my early 30s that I explored European classical. Beethoven symphonies, Brahms, Gould's Goldberg, Bartok string quartets etc. Then I bought a live recording of Rudolph Serkin playing Beethoven's piano sonata op 111. It was mystical and brought tears to my eyes. When he plays that syncopated variation in the arietta.... "This is jazz!", I thought. "This is jazz!' As my father would have said, "Mein Gott im Himmel."

As always you have a unique critical ability to allow non-musicians entry into challenging music.

A cool insight: "This is one of the major problems faced by all critics in any genre: How do you get away from first love? Early moments of initial contact can never be undone. Youthful passions afflict our every judgement. It’s the only real reason any of us are in this game anyway: We are still chasing that germinal intoxication."