David Baker had an unusual trajectory. He grew up as part of the powerful Indianapolis jazz scene that included Wes Montgomery, Slide Hampton and Freddie Hubbard before recording several important early 1960s albums with George Russell.

At that time a car accident curtailed his trombone career, and Baker successfully switched to cello and composition. The great Janos Starker would record the Baker Cello Sonata, which includes a remarkable “Blues” movement.

Baker kept playing cello and did what he could to promote African-American formal music, publishing an important volume of interviews with his peers, The Black Composer Speaks (1978).

However, there’s no doubt that Baker made his biggest impact as a jazz educator. He got in on the ground floor, and was one of the few black faces visible in the late 60’s and early 70’s jazz ed explosion that ranged from North Texas State to Gary Burton’s Berklee to the diverse industries of Jamey Aebersold. In 1966 Baker would start a jazz program at the Jacobs School of Music of Indiana University in Bloomington, and soon IU would be one of the top jazz schools in the country.

As a teenager in the late 1980s I attended the Jamey Aebersold Jazz Camp in Elmhurst, Illinois and worked with David Baker. One day he came in and began singing the bebop anthem “Wee.” He didn’t give us a chart. We had to learn the piece by ear at tempo from his scat singing. He explained, “It’s in B-flat, and goes down in diatonic fourths,” and then got just a bit impatient with us when we weren’t learning the piece fast enough.

In retrospect, this was one of the most helpful lessons I experienced with a jazz teacher in a classroom situation. It was “real life,” it was the way actual jazz musicians communicated with each other.

The most famous recording of “Wee” is at Massey Hall with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach. There’s also a burning studio Gillespie studio recording in the same era with Sonny Stitt and Stan Getz.

The composer is drummer Denzil Best, who also wrote “Move” and helped Thelonious Monk out with “Bemsha Swing.” “Wee” definitely has a Caribbean rhythmic flavor, and according to Wikipedia, “Best was born in New York City into a musical Caribbean family originally from Barbados.”

Two common pieces of jazz ed lingo, “bebop scale” and “contrafact,” were popularized by David Baker. Everyone of a certain age would have seen some of the Baker books like How to Play Bebop. The substantial standalone manuals (The Jazz Style of…) concerning Clifford Brown, Miles Davis, Sonny Rollins, and John Coltrane were state-of-the-art at time of publication.

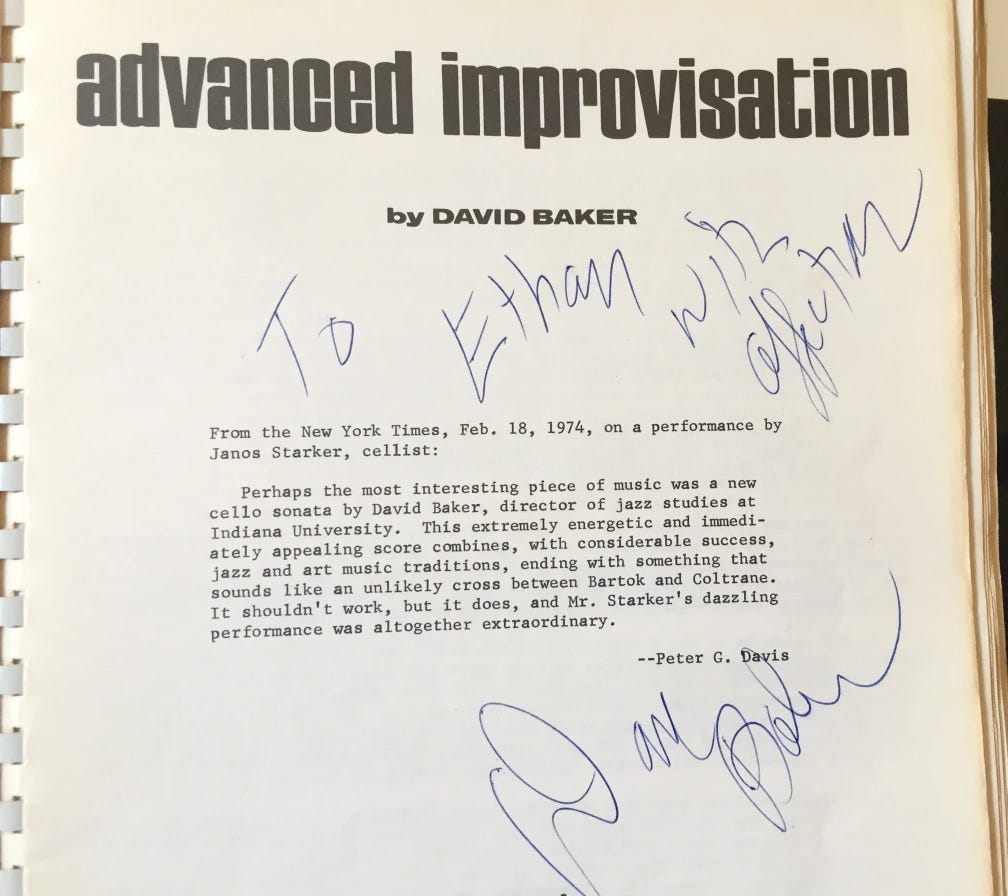

In Elmhurst, Baker gave me something more obscure, Advanced Improvisation (1973). “Advanced” is right! Much of the highfalutin material in this book verges on the ridiculous, like wide leap melodies for “Ladybird” changes made even more avant by a rigorous embrace of avoid tones. (Eric Dolphy seems like Charlie Parker in comparison.) Still, the long listening lists full of Coltrane and Bartók next to each other remain eternally relevant, and paging through this provocative volume helped push me into investigating more 20th-century composition.

I’m touched by the dedication from Baker himself, “To Ethan with affection.”

He came up through jazz, and jazz ed is what paid his bills, but Baker may have been almost more of a natural classical cat. Certainly his large corpus of formal music suggests that he found composition a good fit for his creativity. From Wiki:

You can see it in Advanced Improvisation: his intellect is grasping for esoteric solutions. The title says “improvisation” but — at least so far — many of these kinds of concepts usually need to be written out.

Still, how hip that Baker taught students “Wee” by ear alone!

Footnote 1: To this day I still play “Wee,” especially as a feature for a good drummer. Within the last week those drummers have included Peter Erskine and Nasheet Waits. David Baker is also on my mind because Erskine studied with Baker in Bloomington, and brought in a chart “Blues for David” dedicated to our shared teacher.

Footnote 2: Denzil Best did not record as a leader or in a situation where he was in charge of his most famous melodies. “Wee” was first tracked in the late 1940’s as “Allen’s Alley” with a great “Lester Young meets bop” tenor solo by Allen Eager. (Shelly Manne is on drums.) At that time the tune was less syncopated than when Dizzy played it a few years later; it’s possible that Gillespie modified the melody a bit, or maybe Eager and crew were just a bit square. There’s more written material on that first recording, and there’s also more written material on the Gillespie with Stitt and Getz, including a melody for the bridge. At Massey Hall there is no written bridge, and that’s the way it’s usually been played ever since (thus my chart above). A particularly nice contemporary version is John Scofield with Steve Swallow and Bill Stewart; Sco is bopping like a true master. The excellent drummer Arthur Vint hipped me to Sco’s version; I played “Wee” with Arthur at the Century Room in Tucson two weeks ago.

Footnote 3: Mark Stryker shared a valuable 2003 Free Press interview specifically about Baker’s classical writing. (Baker was resident composer that summer at the Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival in metro Detroit.)

True story: David and his wife, Lida, lived in the first house my parents had built and where I lived for the first two months of my life in Bloomington, Ind., where I grew up. Lida still lives there.

He was a solid player from the J.J. lineage who could deal with more forward thinking music. Interesting to ponder the alternate universe where he continued to play trombone. He might have been the "Interstellar Hard Bop" trombone player which never really existed.

He published these wild trombone method books - I've only seen a few, but they had all kinds of extended technique, way beyond the stuff he was playing with George Russell, into the George Lewis/Ray Anderson/Luciano Berio sound world.