TT 482: Mailbag: Slugs', Art Blakey, Michael Cuscuna

plus my take on Stanley Cowell's BRILLIANT CIRCLES

Thanks to everyone who shared the Nation article or the sidebar on the socials. Nate Chinen wrote about it, and it was picked up by Longreads.

Sometimes when a big article drops the impact dislodges various hitherto unknown puzzle pieces. The major news is “Slugs’ Last Stand,” a substantial article by Tom Colello, who worked at Slugs’ in the immediate aftermath of the murder from May 1972 on. I’ve never read anything like Colello’s memoir, which includes gritty stories about many famous musicians. Truly amazing. Thanks to reader Alexis Lambros David for sending it my way.

Missing from the lovely spread of Steve Lampert handbills was one from the actual week Lee Morgan was killed. The following was sent to me by bassist Wade Mikkola, who got it from “Finnish drummer Matti Koskiala, who was on his way to Berklee to study with Alan Dawson, and had dropped by Slugs while in New York.”

February 1972.

Guitarist Dave Styker sent me a picture posing outside the former Slugs’. When I forwarded to Shuja Haider, Shuja joked: “Smoothies and natural juices—Gurdjieff would have been proud.” (The club was named for Gurdjieff.)

Several years ago I asked Michael Cuscuna for an interview, and we made plans to do it (the same weekend I rented a car in order to talk to Carla Bley), but he canceled and I never followed up. When he died last year I felt a pang of regret, because I had never seen a conversation with Cuscuna that was reasonably candid. However, it turns out in 2000, Lon Armstrong got Cuscuna on the record about Alfred Lion, the head of Blue Note! Thanks to Dave Barber for unearthing this gem. It is in the middle of this All About Jazz pdf. A few highlights:

IN THE VAULT PLAYING GOD: Michael Cuscuna interviewed about Alfred Lion, by Lon Armstrong

MC: I think it was always touch and go at the beginning but he hit a real low point at the end of the 78 and beginning of the 10”LP era, because it had been hard for all the independent labels to go from singles in paper sleeves to suddenly producing artwork, and liner notes, and the printing runs involved. In hindsight we don’t think much about this, but this was a major, major added cost of doing business. And that is why Alfred did not start putting out 10” LPs until 1951 even though they were introduced in 1949, I think.

He told me when the 12” LP came, and he had sweated blood to develop a catalog of about 80 to 85 10” LPs it was “Oh my God, I have got to retool!” What really turned the tide were the two 10” Horace Silver Quintet records that really caught fire and developed what we call the “Blue Note Sound” and were the birth of the Jazz Messengers. They turned the fortunes for him and Blakey and Silver.

(…)

MC: An interesting point is that sales are almost like the movie Groundhog Day — they keep repeating themselves. A reissue will only do relatively speaking as well as the original release did. It can’t change history. If Leo Parker didn’t sell when it first came out, you can put it out five more times and it won’t sell again. The only people I have been able to make a difference with are Tina Brooks and Herbie Nichols. Somehow those broke through and set a historic precedence. But for the most part it is really amazing that no matter what a record did then it will automatically do about the same as a reissue.

(…)

LA: How important were Ike Quebec, and later Duke Pearson, in their roles as A and R directors and assistant producers?

MC: I think Ike was a guy there to sort of co-produce with Alfred, and smooth over any musical mistakes, and he was close to a lot of the younger musicians. He was kind of an Artists and Relations guy, and the guy who could read music and help keep the session on course. And of course he suggested a lot of artists too. Duke Pearson took on a bigger role, because one of his many abilities was as an arranger, and he was a heck of an arranger, and he was someone who could really put sessions together in a highly produced way. His involvement — not on every project but on certain projects ran much deeper. In a lot of ways he moved Alfred into new areas.

For example, “Christo Redentor”: before “The Sidewinder” and before “Song for my Father,” that was the first real crossover success that Blue Note had. And the sextet/septet things that he did for himself and Stanley Turrentine, in many ways a hip jazz outgrowth of the ‘50s Ray Charles band — those were new sounds that he really put together.

(…)

LA: Which years were the most prosperous for Blue Note, and was this prosperity because of a few hit records, or a series of releases in a style that sold successfully?

MC: The biggest years for Blue Note were I think 1964, 1965 and 1966, when “The Sidewinder” exploded, and “Song for My Father” and all the albums that they put out attendant to those did well. Suddenly Blue Note was really a big deal. You saw more ads by them, you heard more spots on the radio by them, and Blue Note really meant something. And also that led to the time that Alfred then sold the label. I think that the pressure of it had a lot to do with the sale of the label too. Because once you have success and you are an independent label of any kind of music, you go through a series of independent distributors that cover different geographic areas, and you ship them records, and you want them to sell them so you ship them more, and they won’t pay you for last release until you have a new release that they want. It is really a game of chasing your own tail. So the more successful he was, the more Alfred had to go out on a limb economically, and the more the pressure there was to match the success. That stress was part of his ill health at the time he sold out. Of course, I don’t know what he would have done. Once he did sell and Frank Wolff and Duke Pearson continued on, the whole jazz scene really came apart. The New York scene was great with Slugs’ and the Vanguard, and a lot of things were happening in the New York club scene, but from a recording standpoint and at radio stations, the whole jazz world started to shrink.

(…)

MC: Of course in the day to day of things a lot of stuff gets lost. He wasn’t looking at it ten paces back as history, he was just dealing with it every day as it came along. And then with guys who had economic problems for obvious reasons would go in there and ask for advances and do record dates just to get the money and he recorded a lot more Grant Green and Lee Morgan than he could ever have issued…

…One of my favorite things that I found was [Lee Morgan’s] Tomcat. People don’t realize that the other album that Morgan recorded around the same time as Tomcat that fell into the cracks was Search for the New Land. That didn’t come out until about five years after it was recorded for the same reason that Tomcat got shelved: The Sidewinder took off and they had to scramble into the studio and cut The Rumproller. And so be damned with these other two records; they weren’t what the distributors are screaming for.

Tom Gsteiger sent me a list of a decade’s worth of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers repertoire for a course he is teaching at Jazzschule Luzern. It’s a hell of a list, over 200 compositions.

(Note: the list does not include the tracks from special repertory projects Lerner/Loewe 1957; Big Band 1957; Les Liaisons Dangereuses 1959; Des femmes disparaissent 1958; Golden Boy 1963)

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, 1954-1964

A Little Busy - Timmons (61)

Africaine - Shorter (59)

Afrique - Morgan (61)

Alamode - Fuller (61)

Along Came Betty - Golson (58)

Alone Togehter (55)

Arabia - Fuller (61; 62)

Are You Real - Golson, Morgan (58; 59)

Art’s Revelation - Mahones (59)

Avila and Tequila - Mobley (55)

The Back Sliders - Shorter (61)

Backstage Sally - Shorter (61)

The Biddie Griddies - Draper (57)

Blue Ching - Dorham (61)

Blue Lace - Morgan (61)

Blue Monk (57)

Blue Moon (62)

Blues March - Golson (58; 59)

Boucing with Bud - Powell (59)

The Breeze and I (60)

Bu’s Delight - Fuller (61)

Calling Miss Khadjia - Morgan (64)

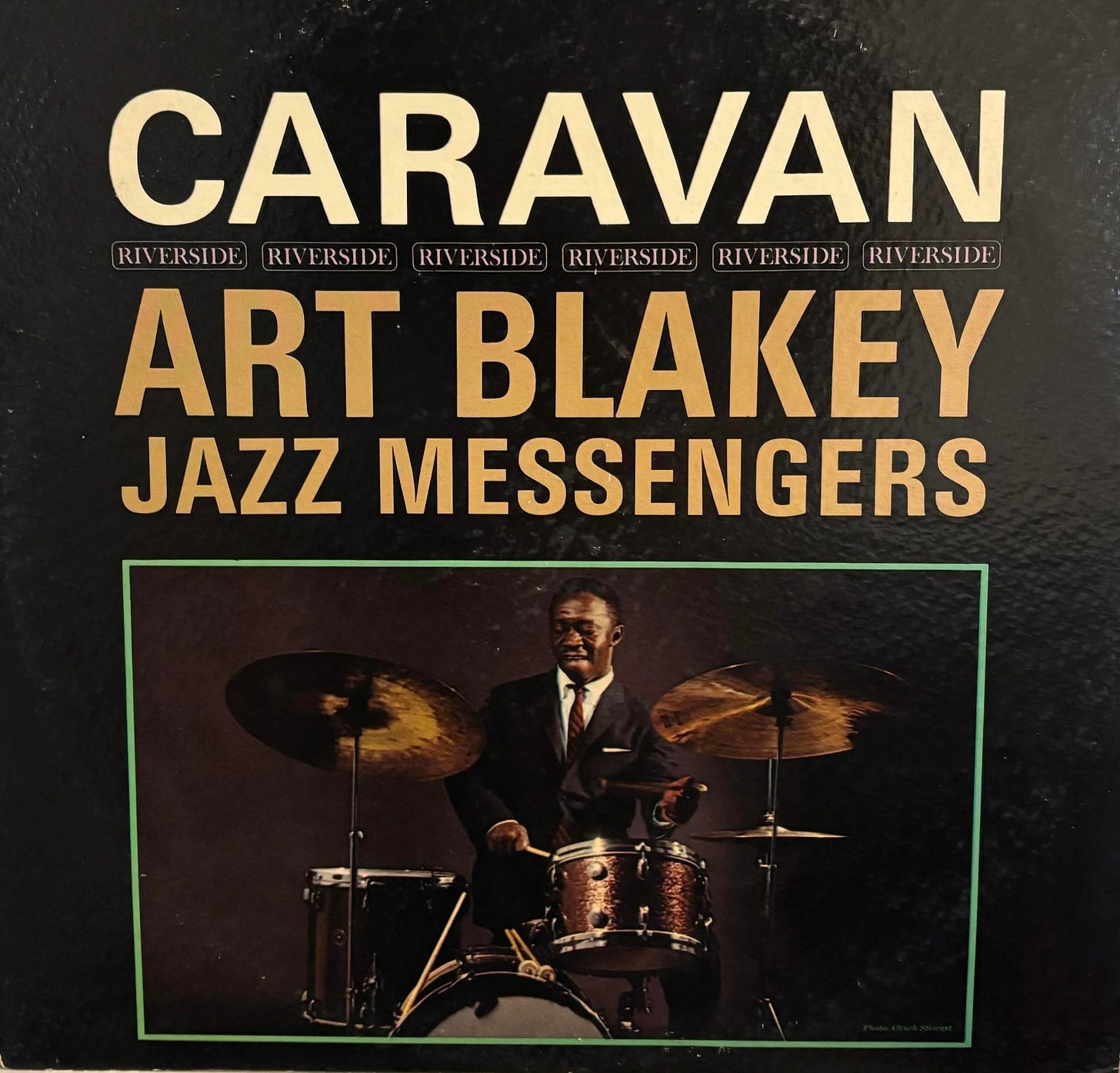

Caravan (62)

Carol’s Interlude - Mobley (56)

Casino - Grye (57)

Celine - Morgan (59)

The Chess Players - Shorter (60)

Chicken an’ Dumplins - Bryant (59)

Children of the Night - Shorter (61)

Circus (61)

Close Your Eyes (59)

Come Rain or Come Shine (58)

Conception - Shearing (63)

Contemplation - Shorter (61)

The Core - Hubbard (64)

Couldn’t it Be You - McLean (57)

Cranky Spanky - Hardman (56)

Creepin’ In - Silver (54)

Crisis - Hubbard (61)

Cubano Chant - Bryant (57)

D’s Dilemma - Waldron (56)

Dance of the Infidels - Powell (59)

Dat Dere - Timmons (58)

Dawn on the Desert - Shavers (57)

Deciphering the Message - Mobley (55; 56)

Deo-X - Hardman (57)

Doodlin’ - Silver (54)

Down Under - Hubbard (61)

The Drum Thunder Suite - Golson (58)

Ecaroh - Silver (56)

The Egyptian - Fuller (64)

El Toro - Shorter (61)

The End of a Love Affair (56)

Eva - Shorter (63)

Evans - Rollins (57)

Evidence - Monk (57; 58; 59)

Exhibit A - Blakey, Sears (57)

Faith (64)

For Miles and Miles - Heath (57)

For Minor’s Ony - Heath (57)

Free for All - Shorter (64)

The Freedom Rider - Blakey (61)

Gee Baby … (61)

Giantis - Shorter (60)

Goldie - Morgan (59)

Gone with the Wind (55)

Haina - Morgan (59)

Hammer Head - Shorter (64)

Hankerin’ - Mobley (55)

Hank’s Symphony - Mobley (55; 56)

Hi-Fly - Weston (59)

High Modes - Mobley (60)

The High Priest - Fuller (63; 64)

Hippy - Silver (55)

Hipsippy Blues - Mobley (59)

I Didn’t Know What Time It Was (63)

I Hear a Rhapsody (61)

I Mean You - Monk (57)

I Remember Clifford - Golson (58)

I Waited for You (55)

Ill Wind (56)

In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning (62)

In Walked Bud - Monk (57)

Invitation (61)

It’s a Long Way Down - Shorter (64)

It’s Only a Paper Moon (60; 62)

It’s You or No One (56)

Infra-Rae - Mobley (56)

Kozo’s Waltz - Morgan (60)

Joelle - Shorter (61)

Johnny’s Blue - Morgan (60)

Just Coolin’ - Mobley (59)

Just for Marty - Hardman (56)

Just one of Those Things (55)

Krafty - Griffin (57)

Kyoto - Hubbard (64)

Lady Bird - Dameron (55)

Lament for Stacy - Morgan (64)

Late Show - Mobley (56)

Late Spring - Mitchell (57)

Lester Left Town - Shorter (58; 59)

Like Someone in Love (55; 58; 60)

Lil’ T - Byrd (56; 57)

Lost and Found - Jordan (61)

M & M - Mobley (59)

Little Hughie - Fuller (64)

Little Melonae - McLean (56)

Look at the Birdie - Shorter (61)

Master Mind - Shorter (61)

The Midget - Morgan (59)

Minor’s Holiday- Dorham (55)

Mirage - Waldron (57)

Moanin’ - Timmons (58)

Moon River (61)

Mosaic - Walton (61; 62)

Mr. Jin - Shorter (64)

My Heart Stood Still (56)

Never Never Land (64)

The New Message - Byrd (56)

Nica’s Dream - Silver (56)

Nica’s Tempo - Gryce (56)

A Night in Tunisia - Gillespie (57; 58; 59; 60)

Night Watch (60)

Nihon Bash - Watanabe (64)

Noise in the Attic - Shorter (60)

Now’s the time - Parker (58)

Off the Wall - Griffin (57)

Olympia - Hicks (64)

On the Ginza - Shorter (63)

Once Upon a Groove - Marshall (57)

One for Gamal - Morgan (64)

One by One - Shorter (63)

The Opener - Mobley (60)

Oscalypso - Pettiford (57)

Out of the Past - Golson (58)

Pensativa - Fischer (64)

Petty Larceny - Morgan (61)

Ping Pong - Shorter (61; 62; 63)

Pisces - Morgan (61)

Plexis - Walton (62)

Politely - Hardman (58; 60)

Potpourri - Waldron (57)

The Preacher - Silver (55)

Prince Albert - Dorham (55)

The Promised Land - Walton (62)

Purple Shades - Griffin (57)

Ray’s Idea - Brown, Gillespie (59)

Reflections of Buhania - Draper (57)

Reincarnation Blues - Shorter (61)

Rhythm-a-Ning - Monk (57)

Right Down Front - Griffin (57)

Ritual - Blakey (57)

Room 608- Silver (54)

Roots and Herbs - Shorter (61)

Round Midnight (60)

S Make It - Morgan (64)

The Sacrifice - Blakey (57)

Sakeena - Blakey (57)

Sakeena’s Vision - Shorter (60)

Sam’s Tune - Dockery (57)

Scotch Blues - Jordan (57)

Shaky Jake - Walton (61)

Shorty - Griffin (57)

Sincerely Diana - Shorter (60)

Social Call - Gryce (57)

Skylark (62)

Sleeping Dancer Sleep On - Shorter (60)

So Tired - Timmons (60)

Soft Winds (55)

Sortie - Fuller (64)

Splendid - Davis Jr. (59)

Sportin’ Crowd - Mobley (55)

Stanley’s Stiff Chicken - Hardman, McLean (56)

Stella by Starlight (56)

Stop Time - Silver (54)

Study in Rhythm - Blakey (57)

The Summit - Shorter (60)

Sweet’n’Sour - Shorter (62)

Sweet Sakeena - Hardman (57)

Tell It Like It Is- Shorter (61)

That Old Feeling (62)

The Theme - Dorham (55)

Theory of Art - Hardman (57)

Thermo - Hubbard (62)

The Things I Love (60)

Those Who Sit and Wait - Shorter (61)

Time off - Fuller (63)

This is for Albert - Shorter (62)

Three Blind Mice - Fuller (62)

Touche - Waldron (57)

Ugetsu - Walton (63)

Ugh! - Draper (57)

United - Shorter (61)

Up Jumped Spring - Hubbard (62)

Uptight - Morgan (61)

Wake Up! - Sears (57)

Waltz for Ruth - Hicks (64)

Weird-O - Mobley (56)

Wellington’s Blues - Blakey (64)

What Know - Morgan (60)

What’s New? (55)

When Lights Are Low (62)

When Love is New - Walton (64)

Whisper Not (58)

To Whom It May Concern - Silver (55)

The Witch Doctor - Morgan (61)

Woody’n’You - Gillespie (57)

Yama - Morgan (60)

Yesterdays (55)

You Don’t Know What Love Is (61)

If forced to choose one Messengers track, I’d go with “This is For Albert” from Caravan. The composition is bliss, and then all of the solos by Wayne Shorter, Curtis Fuller, Freddie Hubbard, and Cedar Walton are truly great. When I interviewed Shorter, I confirmed the legend that it was written for Bud Powell.

EI: You mentioned Bud Powell a second ago. I heard your song “This Is For Albert” was actually for Bud Powell.

WS: Yeah, because Art said he called Bud “Albert.” He said, “Bud. Albert. Powell,” and I said, writing this song, “This is for Albert,” and actually he was saying something like that Bud Powell played at Albert Hall, and I just threw the Albert in there.

One of the distinctive elements is the drum part. In the DTM Jeff Watts interview, Tain gets into “This is for Albert” and polyrhythms a little bit.

EI: Tell me about Art Blakey.

JW: Whenever I lived in Wynton’s apartment on Bleecker Street, Art lived four doors up the hall. So you could just go knock on his door and he’d say, Come on, Jeff! Come on in! You’d go on in and he’d sit and play. He had a baby grand in his living room and he’d play Monk tunes and standards.

(…)

He was just always so cool, man. That beat and that shuffle that will never, ever walk the earth again. Just the natural, African conception and polyrhythmic conception. Brave. It’s one thing to swing but he had it on lock. It’s like locked up like Bernard Purdie or something like that. That cymbal beat, it was like a machine gun or something. Like you have no choice.

I guess after a while I went to so many gigs in town, he would always pull me in, make me play like half a set. He made me do it once in front of Max Roach, which was frightening. I miss him. It was great. He was just so approachable, to be that deep and to have done so much.

EI: Was he among the first to really mix up the hi-hat? I was just listening to “This Is For Albert” after Curtis Fuller died and the hi-hat is very polyrhythmic.

JW: Yeah, I guess between him and Roy Haynes, they both did a lot with the hi-hat.

Art could just do anything. He probably just heard cats doing it and he would just do stuff to show people he could do it. I remember taking a van ride with him to Atlantic City. We were in the van and we’re riding and he’s like, Yes, Jeff. Polyrhythms, you know, it’s no big deal, polyrhythm. You do six over here and you do five with your foot like this. And he was just doing it! You just do that and then you can play in between, you know, playing three over here. He’s just like a natural virtuoso blues musician or whatever.

Caravan is one of the non-Blue Note Blakey albums. Of course, like everyone else, I love the Blue Note sound from the classic years at Van Gelder’s. But Ray Fowler at Plaza Sound Studios for Riverside was good too, and in fact Cedar Walton’s piano — despite being a little out of tune — is sparkling and fresh, especially when compared to the darker palette at Van Gelder’s. This works well, also because Walton is a little broader, bigger, and more conventionally pianistic than the classic Blue Note pianists Horace Silver or Sonny Clark.

I apologized about Free for All. Another notable record that lacked a namecheck in my sidebar was Brilliant Circles by Stanley Cowell, recorded 1969.

It should be a killer LP, but the awesome line-up (Woody Shaw, Tyrone Washington, Bobby Hutcherson, Reggie Workman, Joe Chambers) is saddled with one of the earliest examples of a heavy amplified bass sound. Reggie Workman is great, and he plays great with an amp, but he’s also an x-factor who prides himself on being a rogue element. On Brilliant Circles, Workman is distractingly prominent in the mix when the band is playing at tempo. During the title track, Workman’s busy arrhythmic accompaniment is louder than the trumpet during Woody Shaw’s solo!

I complain about ‘70s bass engineering in the Nation article.

However, if the band isn’t swinging, then that’s a different topic, the rogue bass can fit in as a low blues growl. The highlight of Brilliant Circles is Tyrone Washington’s stunning through-composed march “Earthly Heavens,” a composition that wraps up an era and genre, that moment when black NYC jazz virtuosos embraced European modernism. (Tyrone Washington is a truly mysterious figure, there’s a chance he’s even still alive, although nobody I’ve talked to in jazz circles knows for sure.)

“Earthly Heavens” not Interstellar Hard Bop or the more dominant forms of free jazz. (In the article I cite, “Ornette Coleman’s wrong-note folksong, Cecil Taylor’s wall of atonality, and Albert Ayler’s extended techniques that could erase pitch altogether.”) “Earthly Heavens” is the Arnold Schoenberg/Béla Bartók/Olivier Messiaen area of the era, arguably the finest realization of Gunther Schuller’s idea “Third Stream.”

Eric Dolphy and Sam Rivers were the thought leaders. The discography is mostly on Blue Note: Dolphy’s Out to Lunch, the first two Tony Williams albums Life Time and Spring (both albums essentially co-authored by Sam Rivers), Grachan Moncur’s Evolution and Some Other Stuff, Bobby Hutcherson’s Dialogue, “The Egg” on Herbie Hancock’s Empyrean Isles. In this short-lived genre, the spacious and gleaming pointillism of Bobby Hutcherson was perhaps even more important than any pianist. (Andrew Hill is a little different, sui generis, although he was part of this topic, especially on Hutcherson’s Dialogue.) From the 1970’s onward, most of the more swinging names heard on the those experimental Blue Notes abandoned this style. (Perhaps it is too bad that someone like Hutcherson never tossed in the occasional avant mood piece within a set of conventionally flawless and burning jazz.)

Richard Davis was the key bassist, and Reggie Workman’s avant performance on Brilliant Circles is following the Davis line. It definitely works; it also definitely needs professional consideration when balancing the instruments in the final mix.

The other day I mentioned 70’s pianists and selected a few great moments from their discographies. Stanley Cowell’s Musa - Ancestral Streams from 1974 is a highlight, something else to place on the short list of greatest solo piano albums ever made (alongside the albums I cited by Roland Hanna and Jimmy Rowles). What a groove Cowell gets going on the opening “Abscretions!”

Thanks for the Colello article. I have a Slug's story. I went there a few times in the late '60s or maybe the very early '70s. I saw Sun Ra twice, I think, and Freddie Hubbard another time. I was about 20 and too dumb to be scared of the neighborhood.

Then I went back to college (having dropped out earlier), then to grad school and in 1978 moved to Columbus, OH for my first "real" job. Turned out that a short drive from me was a record shop called Schoolkids Records. It was in a shopping center, I think. When I came in the proprietor and an apparently steady customer were having a conversation about some arcane jazz topic. I brought my purchase to the counter, but the two guys, deep into their conversation, ignored me. I just hung out respectfully and listened.

One of the two guys mentioned Freddie Hubbard. I interjected and said, "Oh, I saw him at Slug's." Their conversation halted immediately. They turned to me and one said, "YOU WENT TO SLUG'S?!!!" I nodded. I didn't realize it was a big deal. I wasn't a deep jazz fan, but I had a friend who was and the two of us would frequently go to clubs. Somehow I had said the magic words, but a touch of imposter syndrome kept me from capitalizing on it. :-)

I regret that I never looked into the Columbus jazz scene. Obviously, from these guys' conversation, there was one. I only later learned that Rahsaan Roland Kirk had been born there. But by the time I moved to Ohio, Slug's had closed and Kirk had died. I probably wasn't aware of either at the time.

Nice to come across Lon Armstrong here - he was a big presence on the messaging board that was on the Blue Note website around 2000 or so. Super-knowledgeable guy and encouraging to me when I was starting to build my Ellington collection.