TT 479: "A Night in Tunisia" and FREE FOR ALL

Two from the great Art Blakey, plus a note about the hapless piano players

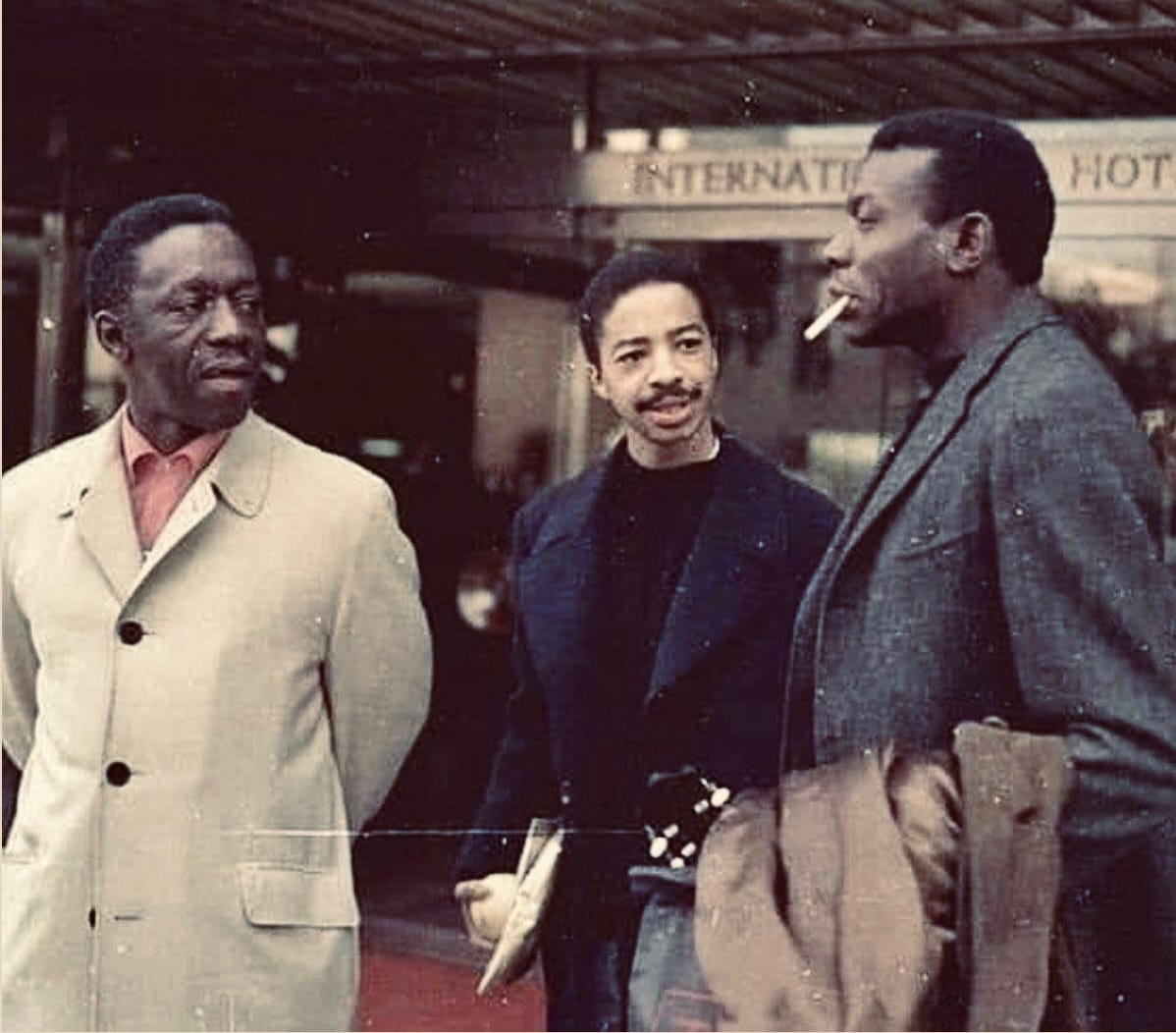

Art Blakey was was the drummer for the Billy Eckstine bebop orchestra with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie; one of Bird’s best records is the live session at Birdland with Fats Navarro, Bud Powell, Curly Russell, and Blakey; some of Thelonious Monk’s fabulous early trio sides feature Blakey in a notably interactive role.

Blakey was then eager to become a leader and add more blues, gospel, and shuffle into the mix. Hard bop began as a concept shared with Horace Silver, but it was a slightly later edition of the Jazz Messengers with Bobby Timmons on piano that would track Blakey’s definitive hit record, Moanin’.

When I asked Billy Hart about Art Blakey last week, Billy brought up Dizzy Gillespie’s “A Night In Tunisia.”

Dizzy was also a competent percussionist with claves or conga, and he acquired some that knowledge from an indisputable source, Chano Pozo. Later on, Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers would play Gillespie’s “A Night in Tunisia” every night on tour for decades, and frequently the members of the band would also play percussion instruments. As far as I understand it, George Russell gets some credit for the kind of harmonic thinking we call “modal,” and Russell worked some of that out for charts like “Cubana Be-Cubana Bop” written for the Gillespie big band with Pozo. Modal jazz and latin music go together, and you can trace the line of thinking from bebop to modal jazz in Art Blakey performances of “A Night in Tunisia” through the years. I especially love the edition of the Messengers with Lee Morgan and Wayne Shorter, and my favorite Blakey album remains A Night in Tunisia, with both horn players taking a cadenza at the end at the title track. Blakey would play his same “Night in Tunisia” introduction for 40 years, and I’m glad he did, for that drum solo was a masterpiece.

It’s true that the blowing on the Art Blakey versions of “A Night in Tunisa” has a near-modal cast. The piano players would comp Gillespie’s progression, E-flat dominant to D minor, but the horns would solo more or less in D minor. This subtle rub would play straight into the modal vortex of ‘60s jazz.

“So What” from Kind of Blue gets the credit for the modal revolution, and it does deserve a lot of the credit, but after talking to Billy Hart I’ve realized that “A Night in Tunisia” should be in the same conversation. The African-aligned burn of classic Art Blakey performances foreshadows the fervent chant of Coltrane/Tyner/Elvin.

For the essay “Jazz Off the Record” for The Nation, I supplied a sidebar of recommended listening. The first part is early ‘60s jazz classics known to most serious fans, the second part has what little there is from the 1967-1972 period.

I’m pretty happy with my choices, but inevitably certain things got left out. Perhaps the biggest omission is Art Blakey’s Free For All, which might have the fiercest Blakey drum performance on record along with stellar compositions and solos by Wayne Shorter and Freddie Hubbard. The year is 1964, and the general harmonic and rhythmic idiom is absolutely of a piece with the rest of my sidebar.

This will draw some gasps of horror, but I never really loved Free for All the way many others do.

On both the title tune and “The Core,” Blakey is relentlessly playing odd-meter groups like 3/4 against the 4/4 time. It’s exciting, especially at first listen, but after a while it feels a bit forced. I wonder if Blakey is trying to outdo comparative newcomers Elvin Jones and Tony Williams in the loud and busy department.

As far as I know, Blakey didn’t usually hit this hard. It might have been a surprise to the other members of the band. Rudy Van Gelder’s studio was medium-sized, no one had headphones, the musicians needed a certain amount of extra-sensory perception to collectively play the beat. During much of the LP, the rhythm section is barely together, and about two and half minutes into “Free For All,” the time gets turned around behind Wayne Shorter. Almost a full chorus is unclear. I don’t usually care about this kind of mistake, but in this case an uncommon structural error strengthens my suspicion that this session was rather fraught.

The track I like best is “Hammer Head,” where Blakey reverts to type, playing his peerless shuffle, straight down the middle. Wayne Shorter blows a glorious solo.

Cedar Walton is one of the greatest jazz pianists, but he sounds uncomfortable on Free For All, especially when conscripted into a high-energy post-McCoy Tyner role on “The Core” and the title tune.

In general, the pianists really took a beating in the 1960s. McCoy Tyner was unbelievably strong, maybe the strongest of all time, and his example led many others to helplessly flail and bang away next to loud drummers.

Elvin Jones was one thing: somehow, there was always transparency in Elvin’s sound. But not every other drummer could create that intensity while leaving enough headroom for the acoustic piano.

Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, and a host of others soon took up the electric keyboard. It was simply one way to survive.

In the 1970s, at the height of the fusion movement, a few seriously swinging pianists refused to bow to the latest fashions.

Cedar Walton has pride of place, A Night at Boomers and Eastern Rebellion for starters. But Walton was not the only one. Barry Harris, Tommy Flanagan, Hank Jones, Roland Hanna, and Jimmy Rowles all started making some their best records in the same era. This was not the music played at Slugs’ and discussed in my Nation article, it was something less intense, less modal, and less chromatic. Despite turning down all the knobs on the mixer, the sounds were still modern jazz and still truly great. In a world that had gone past the ferment of the ‘60s into the era of electric keyboards and big beats, these superb pianists commanded the terrain of exploratory bebop and blues in a relaxed and timeless manner. Two of the LPs on this short starter kit below, Hanna’s Swing Me No Waltzes and Rowles’s Plays Ellington and Billy Strayhorn, rank with the most extraordinary solo piano albums ever made.

Cedar Walton A Night at Boomers (1973) Eastern Rebellion (1975)

Barry Harris Magnificent (1969) Live In Tokyo (1976)

Tommy Flanagan Ballads and Blues (1977 ) Thelonica (1982)

Hank Jones Bop Redux (1977) Kindness Joy Love and Happiness (1977, with The Great Jazz Trio)

Roland Hanna This Must Be Love (1978) Swing Me No Waltzes (1979)

Jimmy Rowles The Special Magic of Jimmy Rowles (1974) Plays Ellington and Billy Strayhorn (1981)

Four footnotes.

1. Today is Cedar Walton's birthday. He would have turned 91. (1/17/34).

2. Your six pianists include the midcentury fearsome foursome of Detroit -- Hank, Barry, Tommy, and Roland. #JazzFromDetroit

3. Few piano trio LPs are in the Interstellar Bebop canon, but it's not a coincidence that the two prime examples, "Now He Sings, Now He Sobs," and "Time for Tyner" have drummers with fundamentally light cymbal beats -- Roy Haynes and Freddie Waits. (Yes, McCoy's side is technically a quartet with Bobby Hutcherson, but my larger point stands.) .

4. To further link "Night in Tunisia" to forthcoming modal jazz, did you ever notice that a chunk of the A section changes of Wayne's "Black Nile" are the same as "Night and Tunisia" backwards (D minor/E-flat 7)? That can't be coincidence given the title.

Carry on.

Would love for you to write something specifically about percussive-ness/how piano players hit! To me Monk hits harder than his contemporaries, interesting to think how that influence played out, also Don Pullen, Jaki Byard, Stanley Cowell are all people I think of hitting kinda hard, not in the McCoy way, but still jazz musicians. And there's also the discussion of Cecil, Muhal, any other improvisers...