TT 474: New from Mary Lou Williams

Important article by Sarah Caissie Provost sheds further light on difficult topics including Scott Joplin, plus Alice Coltrane interviewed by Branford Marsalis

The Journal of Jazz Studies out of Rutgers oversees the production of academic articles. From the latest batch, I’m particularly happy to have “We Have No More Creators: Mary Lou Williams Performs the Jazz Canon” by Sarah Caissie Provost.

Provost uncovers a few spicy details that are brand new.

After being present for triumphs of the swing era, Mary Lou Williams stayed in touch with what was current. Thelonious Monk and Bud Powell were disciples; Monk even played her arrangement of “All God’s Children Got Rhythm.” In time, Williams composed large scale concert and religious works (I write about Aaron Diehl’s recent recording of Zodiac Suite here) before tracking one of the great piano trio albums of the 1970s, Free Spirits with Buster Williams and Mickey Roker (I write about Free Spirits here).

While Free Spirits is essentially contemporary in outlook (there are even pieces by Bobby Timmons and John Stubblefield) the pianist had another side as historian and curator. As early as 1955 she produced one of the first retrospective LPs, A Keyboard History. (The critics were ready to celebrate such an event, and the album was awarded 5 stars in Downbeat.) A later album of discussion and music The History of Jazz was recorded in 1970 and released 1978.

She took a position at Duke University in 1977; the Mary Lou Williams archives at Duke University and at the Institute of Jazz at Rutgers is where Sarah Caissie Provost discovered the goodies she presents in “We Have No More Creators: Mary Lou Williams Performs the Jazz Canon.”

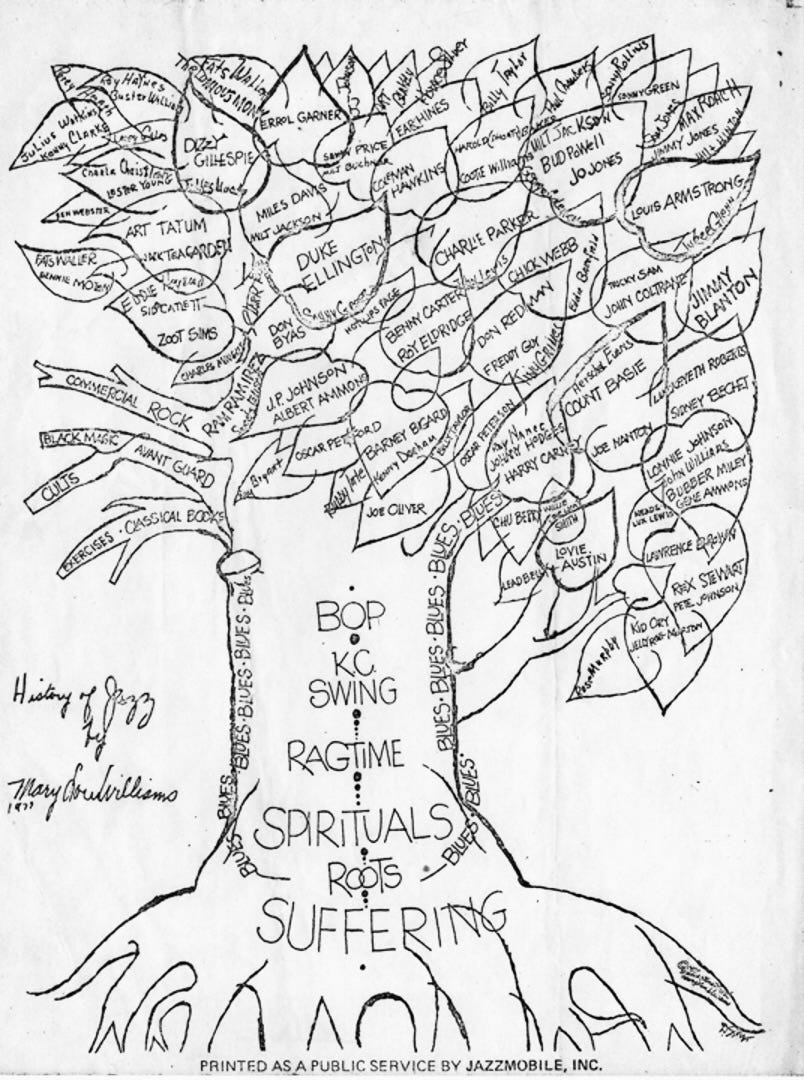

In recent years the “History of Jazz” handout has been widely shared online. It was created for the Harlem Jazzmobile by Mary Lou Williams and drawn by noted illustrator David Stone Martin.

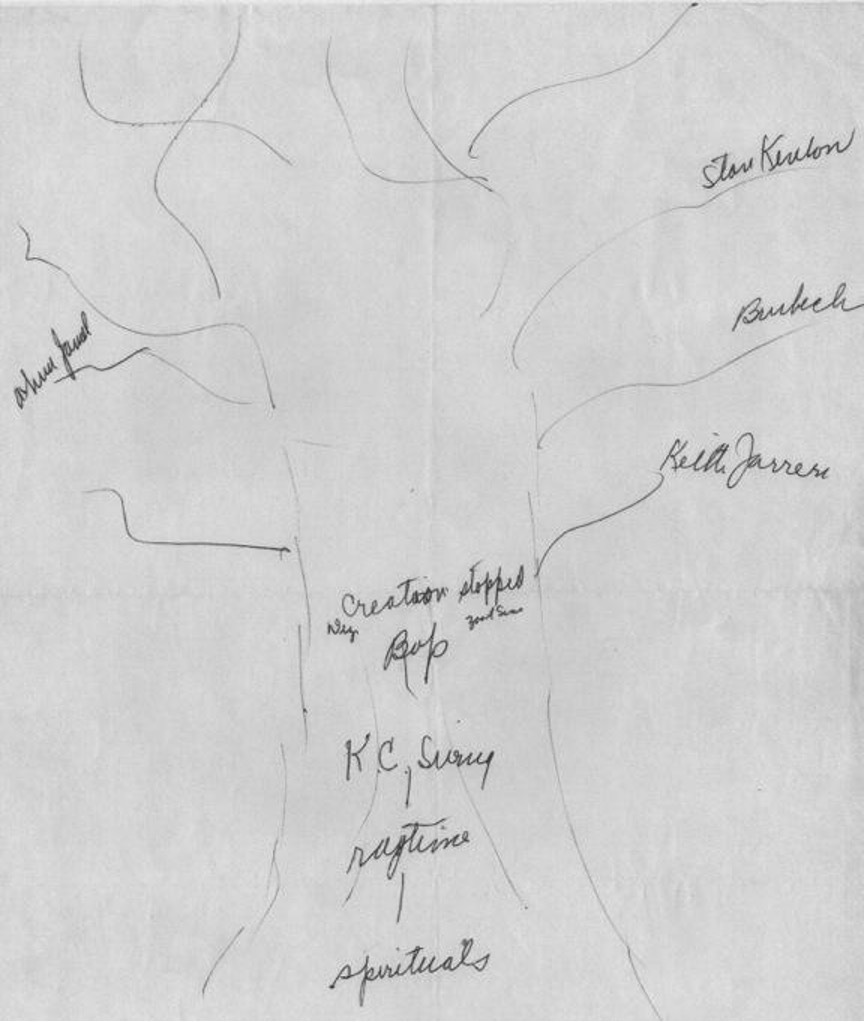

Thanks to Provost’s research, we now know that Williams had planned to do a jazz tree of people she didn’t like!

For a tree of barren branches, after bop, she wrote “Creation stopped,” and declared Stan Kenton, Dave Brubeck, and Keith Jarrett to be dead ends.

This is not an enormous surprise, for Kenton, Brubeck, and Jarrett were wildly successful white cats with an approach that could prioritize European techniques. (There are not so many white musicians on the “good” jazz tree other than soulful swingers Zoot Sims and Jack Teagarden.)

More unexpected is the inclusion of Ahmad Jamal in a negative fashion as a dead branch. Probably this is a political or religious decision: Williams had converted to Catholicism, and seemed to be critical of those that took a Muslim name or participated in Black Nationalism. (Jamal was born Fred Jones.)

“It’s time to give credit and honor to slaves,” she writes in a private document unearthed by Provost. According to Williams, Miles Davis, McCoy Tyner, Ahmad Jamal, and Billy Taylor were all “ashamed of slaves.”

To be clear, this broadside surely does not reflect what Davis, Tyner, Jamal, or Taylor felt or would say about this matter. Indeed, Williams is quite outside the pocket at this moment. She’s just being old, grumpy, and Catholic.

However, this new information helps remind us that the black jazz greats did not agree on everything just because they are the black jazz greats. The narrative might be smoothed out for the general history books, but when we look closer, the surface turns out to be bumpy.

In a particularly revelatory passage, Provost discusses Mary Lou Williams’s unhappy relationship to Scott Joplin.

Williams identifies jazz as a fundamentally Black American art through these lecture-recitals. This causes her to depart, sometimes significantly, from other descriptions of jazz’s periods, even if she utilizes similar style names. For example, she argues that Scott Joplin, known to most as “the father of ragtime,” played music that was not authentically American—thus not jazz-adjacent, but rather “European.” Williams categorically excludes Joplin from ragtime, not only for this reason, but also through her chronology of jazz history—she cites ragtime’s genesis at “more or less the style around the time of World War I” (Joplin died in 1917 after publishing rags for more than 15 years).

I have an idea of what Williams is getting at, and will try to offer an explanation below, but it is obviously ridiculous to say “Scott Joplin isn’t ragtime.” Joplin is literally ragtime. The first piece of sheet music to sell one million copies in America was Joplin’s “The Maple Leaf Rag” in 1900. On his music he repeatedly wrote, “Do not play this piece fast. It is never right to play ragtime fast.” Every ragtime performer ever, anywhere, plays Scott Joplin. The composer and the genre are virtually synonymous.

Provost doesn’t mention this, but Mary Lou Williams herself played and recorded Scott Joplin.

Father Peter O’Brien was Williams’s sponsor and producer in the 1970s. According to O’Brien’s liner notes for NiteLife, she agreed to participate in his 1971 ragtime event and play Joplin somewhat under protest; perhaps the priest was calling in a favor. The best of the three Joplin pieces on NiteLife might be “Elite Syncopations.” Williams swings Joplin’s lines and improvises quite a bit. The audience seems to know the original, for they laugh and shout encouragement at her emendations. It’s a marvelous document.

(There are other recordings of Joplin by jazz greats, including Jelly Roll Morton, James P. Johnson, and Hank Jones. Jones plays them reasonably “as is” but with a swing feel, while both Morton and Johnson are in line with Williams, adding blues riffs and fancy runs.)

Frankly, it’s hard for me to believe that Mary Lou Williams didn’t care for the best Joplin tunes. After all, she’s clearly having a good time with “Elite Syncopations.”

If the problem isn’t musical, it must be political.

After Joplin wrote out piano pieces, outsiders had access to a private community truth. Indeed, Joplin is the quintessential incorrect delivery system of black music to the white masses. Joplin’s music still manages to sound pretty great when played “as-is” with an unsteady beat.

By the time Williams was issuing pronouncements about Joplin being “European” to her Duke students, she would have had to sit through the massive success of The Sting, the extremely Caucasian 1973 hit movie that created another ragtime revival. (The previous ragtime revival with the white man’s derby, sleeve garters, and cigar had begun in the 1950’s.)

Ever since The Sting, piano teachers everywhere have assigned easy Joplin as light entertainment. After their charges sort of get the notes, the teachers put a gold sticker on the page and move on to “something more serious” like easy Beethoven. Nothing deeper is learned.

The blues can’t be notated. Neither can swing.

This scientific truth plays into the way some jazz masters want to deny sheet music. Of course, these same masters also read sheet music all the time. A well-rounded talent like Mary Lou Williams was naturally comfortable with notation: She even wrote full charts for Andy Kirk’s big band. Williams simply thought something else should come first.

Related topics come up in this recent upload of Alice Coltrane interviewed by Branford Marsalis. It is just fantastic to hear Alice discuss Detroit, New York and John Coltrane.

At 10 minutes in, Alice Coltrane starts talking about how environment is so important, and says that young people shouldn’t be too involved in academics too early. Alice says young people should start with the blues.

A notably relevant passage is spoken by Branford Marsalis at around the 16 minute mark.

Branford Marsalis: “I feel very fortunate I’m from New Orleans. The majority of the musicians I played with couldn't read. There were all these songs that you just had to learn in the air…When you go to a place where everybody reads and they learn songs from books… To me learning songs from books is like trying to learn a language from a book. It's just not going to work. It's impossible.”

Alice Coltrane: “Maybe you didn't have to be born into it but you had to live it, you had to experience it. You can't be on one shore listening and then say, ‘Oh, I can do that.’ It's a good copy but it's not the real thing.”

It is in this context that I place Mary Lou Willams’s dismissal of Scott Joplin. To use Alice Coltrane’s term, Joplin’s notated scores are on another “shore.” For Williams, Coltrane, and Marsalis, the community is the first teacher. Pieces of paper with musical notation should arrive later in the process.

Both A Keyboard History and A History of Jazz include fast-paced ragtime/stride pieces deliberately retro in style, perhaps reminiscent of James P. Johnson’s Harlem works from the 1920’s such as “Carolina Shout” or “Keep Off the Grass.”

On A Jazz History (1955) Williams kicks things off with the brilliant original “Fandangle.” In terms of sheer piano chops, “Fandangle” is breathtaking. The phrase lengths of the composition are delightfully off-kilter and unpredictable, while drummer Osie Johnson supplies cheerful rim clicks.

The History of Jazz (1970) includes “Who Stole the Lock Off the Henhouse Door.” The pianist hesitates a bit at the start — keeping one’s left hand in shape for this kind of workout is no joke — but soon finds her stride (pun intended). It’s the real deal.

Although the racy title “Who Stole the Lock Off the Henhouse Door” is shared with a novelty blues number still heard in hillbilly string bands, this Williams piece is different, a fancy elaboration of something reportedly learned early on from her mother, who played and taught piano.

Both of the Mary Lou Williams history albums have selections connected to youthful experiences singing songs and dancing with her family and her community — in other words, a process very different than reading Joplin ragtimes from a book.

I sure wish I could have attended some of the classes taught by Mary Lou Williams at Duke University. From Provost’s article:

Her students, despite being nonmusicians, were expected to listen and vocally reproduce what they were hearing immediately…Williams placed a lot of faith in her musically green students. In one example, she teaches several versions of “I’m In the Mood For Love.” First, she plays a version by Charlie Parker, followed by another by James Moody. Finally, she plays King Pleasure’s “Moody’s Mood for Love,” a vocalese version of Moody’s solo from the saxophonist’s recording of the tune. She also plays the original melody several times on the piano. The class is given no pedagogical reason for learning these songs until halfway through the second class session—a full hour and a half after they began the exercise. At this point Williams tells them, “you’re improvising,” a surprising statement since few people would consider what they were doing—singing someone else’s music note for note—improvisation. The exercise is difficult, and the students struggle with King Pleasure’s rapid vocal line. Despite its difficulty, the students are experiencing jazz’s “good feelings” rather than hearing an academic viewpoint.

Williams must have had the patience of a saint when teaching amateurs King Pleasure’s “Moody’s Mood for Love,” for this is a hard piece of vocal music. I know Catholics are into penitence, but good grief.

Despite its speed and virtuosity, the bebop music of Charlie Parker remained close to soulful vocal music and the blues. This is surely the point Mary Lou Williams is illustrating when assigning “Moody’s Mood for Love” to a classroom.

(Trivia: choreographer Mark Morris once accurately sang the full “Moody’s Mood for Love” at a Mark Morris Dance Group cabaret accompanied by The Bad Plus.)

It would be a valuable project to collate, annotate, and compare the history-minded records, lectures, and texts of Mary Lou Williams alongside those of Eubie Blake and Art Hodes. Between the three of them we might end up with a pretty good picture of how jazz piano was created!

James P. Johnson coda: Johnson published basic notation of the pieces mentioned above, “Carolina Shout” or “Keep Off the Grass,” but nobody ever thought a straight play through of a Johnson score in the manner of Joplin was the answer, especially since Johnson’s records were so much more advanced than the sheet music.

That said, Johnson’s own scores should be part of the source material. For decades they were impossible to find, but now both “Carolina Shout” or “Keep Off the Grass” are uploaded to IMSLP.

A favorite Mary Lou Williams recording of mine since childhood was the albums Giants, released under Dizzy’s, Bobby Hackett’s and Williams’ names (on Perception label, 1971), those 3, Grady Tate and George Duvivier. Recorded live at Overseas Press club in NYC imperfect audio and balance (horns, esp. Hackett, are often off-mike), but you can certanly hear and physically experience the great feel. Williams’ playing is so strong, driving, and alive. I remember thinking then, and now (i found a cd copy on a 2-fer on coll

Magnificent! Thank you for writing this Ethan…