TT 360: February Open Forum

"How I long to be the man I used to be! Fascinating Rhythm, oh, won't you stop picking on me?"

The comments section on this post is temporarily open for all readers (usually it is for paid subscribers only). The previous threads were pretty active and interesting, so: Say what is on your mind, drop your hottest take, or ask me anything — but please keep it clean and civil.

When I came up with the idea of calling Rhapsody in Blue “The Worst Masterpiece,” I texted friends looking for their guesses.

“I am writing about the Worst Masterpiece. What piece do you think I’m writing about?”

Ravel’s Bolero was the default popular selection. Other nominations included Orff’s Carmina Burana, Wagner’s Parsifal, and — perhaps surprisingly — Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. (I admit that I like the first two movements of that symphony better than the last two.) Brubeck/Desmond “Take Five” was offered — certainly valid — until I explained the genre was classical music. Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess was also in the chat.

When I revealed my answer, everyone agreed that Rhapsody in Blue was the best choice, that it was indeed the Worst Masterpiece.

There is a long tradition of criticizing Rhapsody. Leonard Bernstein’s 1955 “it’s not a real composition” comment is famous:

Rhapsody in Blue is not a real composition in the sense that whatever happens in it must seem inevitable, or even pretty inevitable. You can cut out parts of it without affecting the whole in any way except to make it shorter. You can remove any of these stuck-together sections and the piece still goes on as bravely as before. You can even interchange these sections with one another and no harm done. You can make cuts within a section, or add new cadenzas, or play it with any combination of instruments or on the piano alone; it can be a five-minute piece or a six-minute piece or a twelve-minute piece. And in fact all these things are being done to it every day. It's still the Rhapsody in Blue.

I knew I was being provocative with my New York Times debut, “The Worst Masterpiece: Rhapsody in Blue at 100,” but I admit I hadn’t considered the NYT comment section, which I have since learned is famously toxic. Perhaps I should have gone with a less incendiary title, for it is clear that many of the most rabid commenters only read the title (and not the article) before jumping in with both feet.

I still love the title “The Worst Masterpiece.” It is a title that can only be used once, and it remains the perfect sobriquet for Rhapsody in Blue.

Anyway, as my friend Heather Sessler put it: “Achievement Unlocked.”

Those of us in the jazz world sometimes joke, “For classical musicians, time is a magazine.”

This is not true, of course. Rhythm is important to great classical musicians. It’s just that the treatment of rhythm is so different.

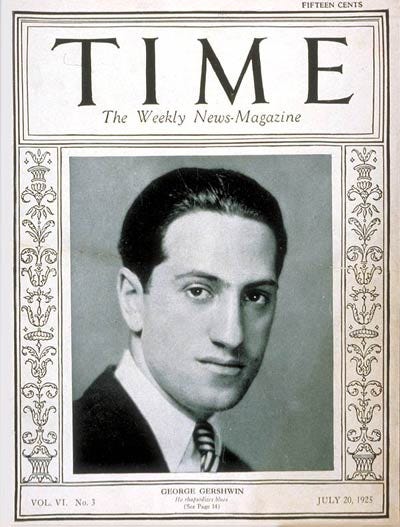

Gershwin was on the cover of Time in 1925 with the descriptor, “He rhapsodizes blues.” It would be 24 years before a black musician was on the cover of Time; Louis Armstrong arrived in 1949.

Gershwin died so young. We don’t know where he would have taken his journey. The fact that he insisted on an all-black cast for Porgy and Bess was a provocative choice. Gershwin’s biographer Howard Pollack suggests that the composer was gradually becoming more leftist as he got older.

When preparing for performance at the St Endellion Festival two summers ago, I listened to many recordings of Rhapsody. Since publication of my essay, I’ve been sent over a dozen re-workings, usually with the suggestion that this is the way to make Rhapsody better or more swinging. I was already aware of many of these alternates, and frankly have little appetite for much more Rhapsody at this juncture.

Aaron Diehl and Marcus Roberts both impress with their groove when they improvise in concert, and I played a bit of my own Jaki Byard-inspired cadenzas in performance at St Endellion. Even someone as non-jazz as Yuja Wang includes her own subtle “jazzy” alterations to the score.

One of my comparatively few visible supporters in the Rhapsody discourse has been Darcy James Argue, who linked to the Ellington band’s 1962 performance in a beautiful pocket arrangement by Billy Strayhorn. Darcy writes, “To me, this is by far the most satisfying version of RiB, from Harry Carney’s opening trill through to the audacious polytonality of the final chord. It’s also the shortest, clocking in at under 5 min. — a perfect distillation by Strayhorn, and a great moment in American music.”

It makes sense for jazz musicians to make Rhapsody in Blue their own. However, to really assess the work clearly, the work needs to be heard “straight” with the most familiar Grofé orchestration, in other words the version that has permeated our culture.

For the audio embed in the NY Times article, I selected Eugene List’s performance. List may not be well-remembered today, but he was just marvelous in rhythmically-charged performances of Gottschalk and Chávez, and his 1981 record of Rhapsody with Erich Kunzel and the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra supplies just what is required in terms of conventional pianistic and symphonic glamour.

In 1998, Stanley Crouch offered an interesting take on Gershwin for The New York Times, “An Inspired Borrower of a Black Tradition.”

Again, the comments section is open to all for a few days. Ask me anything, it doesn’t need to about Gershwin, or simply state your piece. If you don’t chime in this time, I will host another open thread at the top of March.

(UPDATE: The comments are now closed.)

Perhaps Strayhorn's masterful condensation might be compared to Gil Evans's rethinking of Concierto de Aranjuez? Rodrigo was apparently appalled by the "blasphemy." But I can't imagine any jazz listener, or serious student of composition, agreeing with him. Evans fleshed out the ideas that were merely hints in the "original," in particular turning the ominously static development section into a full-blown and coherent narrative. Perhaps Strayhorn, too, undertood the composer's ideas better than the composer...

You call it a masterpiece! What more do people want?