Hiroko Sasaki and I met in the early 1990s when we were both college students. I’ve always admired her playing, but only just recently have we started getting together and collaborating at the piano. The first fruits of our teamwork was the discovery of an unheralded Chopin variant, written up here at TT last month: “The Mystery of Chopin’s Thirds.”

Now that Hiroko and I are practicing a bit of four-hand Schubert and Dvořák repertoire, I’ve started making sketches for my own four-hand arrangements and compositions. The “big piano” with 20 fingers is such a great playground.

It’s also Hiroko’s birthday today! Happy Birthday Hiroko!

Hiroko’s recording of both books of Debussy’s Preludes is a significant disc, both for the stellar playing and the unique instrument.

Debussy composed the preludes between 1909 and 1913. We will never know what his pianos sounded like, but they undoubtedly were closer to the 1873 Pleyel on Hiroko’s record than a perfectly regulated modern Steinway that exhibits no blemishes whatsoever. Under Hiroko’s hands, the bass notes on the Pleyel grunt, the middle register is exceptionally mellow, and the high octaves have a bit of screech.

To be clear, it’s still very tasteful! Often “historical piano” recordings are simply too extreme and weird, but this record offers exceptional atmosphere as well as exceptional playing.

Debussy’s piano writing rewrote the rules of structure and sonority in European music, and these preludes still have the power to shock.

The composer reveals each movement’s evocative title only at the end of the page.

Five favorite preludes:

Le vent dans la plaine (The Wind in the Plain)

It’s a virtuoso piece, of course. But so often these days there is something like an arms race among pianists to play the figurations as fast and as even as possible. On Hiroko’s Pleyel it’s impossible to manage the final millimeters of repetition and tonal control. Just a taste of human imperfection is inevitable, and therefore gloriously true to the “wind” of the title.

Debussy’s cascades of descending sixth and seventh chords gesture towards Duke Ellington.

Les collines d'Anacapri (The Hills of Anacapri)

Anacapri is a famous tranquil resort spot in Capri, and these melodies have a decidedly Italianate feel. Debussy’s harmony is intentionally “rustic,” but the vertical structures also conjure bells, and at times even the blues.

The end offers a famous extreme moment in the literature, where the music flows up to the very top of the piano, marked “luminous” and extremely loud. A modern Steinway seeks to have the top octave relate smoothly to the rest of instrument. No such politicking is possible on the Pleyel, and Hiroko makes the most of this joyful shout.

La cathédrale engloutie (The engulfed Cathedral)

If forced to choose only one Debussy Prelude, the nod would go to La cathédrale engloutie. Poetry and mystery align with parallel harmonic thinking; the final product seems simultaneously antique and modern.

Wikipedia explains, “This piece is based on an ancient Breton myth in which a cathedral, submerged underwater off the coast of the Island of Ys, rises up from the sea on clear mornings when the water is transparent.”

“Without nuance” (sans nuances at the end of the first page) is a quintessential Debussy marking. What composer before Debussy would have thought to use such a direction?

The low “C” on the Pleyel gets a workout, offering a very different sound than most low “Cs” on other modern recordings. Hiroko dares to play the long fortissimo “organ” section (Sonore sans dureté) under one pedal. It’s just awesome.

Feuilles mortes (Dead Leaves)

Several Debussy pieces foreshadow late ‘50s jazz harmony. I’d bet my bottom dollar that Bill Evans played through the phrases of Feuilles mortes. One can almost hear Kind of Blue at certain moments. Even the title relates to a famous jazz standard that Bill Evans played on countless gigs: “Autumn Leaves” is based on "Les Feuilles mortes" by the French composer Joesph Kosma. (Apart from the title, the two pieces are not related musically, although Evans would play plenty of stuff on “Autumn Leaves” that he seemed to have learned from Debussy.)

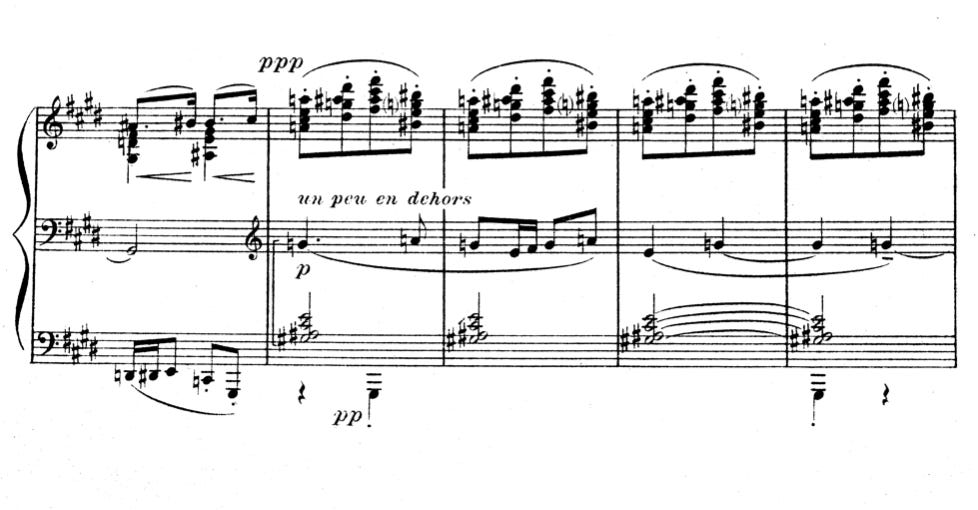

Debussy is writing on three staves. It is not so very complicated at first, but as the piece progresses, a true middle line emerges for a few bars. Hiroko’s control of the counterpoint is masterful.

“Général Lavine” – eccentric

Yes, this is a rag inspired by Scott Joplin and his peers. Debussy even gives the tempo marking, “Dance in the style of the movement of a Cake-walk.” Apparently Lavine was a comic actor who was dressed half as a soldier and half as a clown.

Not every classical performer can let themselves be goofy. Hiroko Sakasi, an amusing person herself, is plenty silly in “Général Lavine” — not that she doesn’t nail the whip-like repeated note figuration. Again, the Pleyel gives the final “eccentric” touch to a superior production.