One of Chopin’s most famous Études is op. 25 no. 6 in G sharp minor. It’s very hard and very beautiful, a touchstone of the virtuoso repertoire.

Last week Hiroko Sasaki and I were sitting at her piano, comparing fingerings for Chopin’s chromatic scales in thirds. While I was playing the first page of op. 25 no. 6, she told me sharply, “A-natural.”

I looked at her like she was crazy, and shot back, “Where’s the score?”

If you aren’t involved in classical music performance, it might come as a surprise that there is no single agreed-upon version of familiar masterpieces. Many early publications were riddled with mistakes; later, in the 19th-century, editors went wild marking up Bach and Beethoven with extraneous detail. In the 20th-century there was a return to a bare bones approach, where the autograph was treated as holy writ, resulting in fresh publications proudly calling themselves an “Urtext.”

For a variety of reasons Chopin is a bit more complicated to sort out than many composers, in part because so many great pianists made important editions. Even the most stern proponent of “obey the composer — no matter what!” would concede that Chopin deserves a certain amount of freedom and personality from the interpreter.

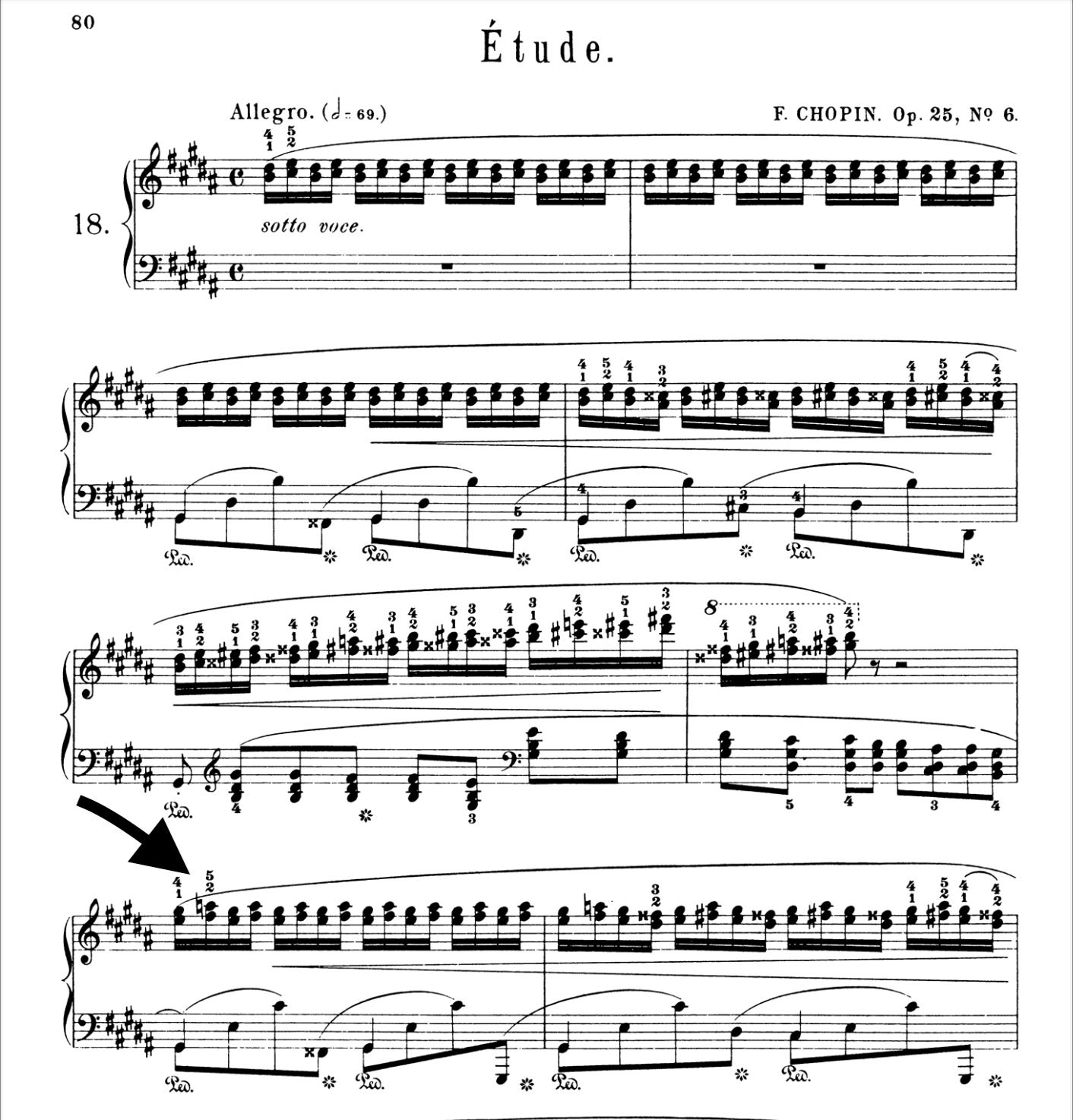

Hiroko brought out her copy of the études, informally known as the Paderewski edition, published in 1949 by the Polish editorial board of Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Ludwik Bronarski, and Józef Turczyński. At the time it was considered to be the most reliable edition yet produced. Newer editions might have more respect from musicologists (Charles Rosen called the Paderewski edition “an international scandal”) but this edition is still popular among pianists. (I personally like this edition because I know that Paderewski, Bronarski, and Turczyński thought about the music from the vantage point of working professionals; also, if I don’t appreciate their suggestions, I am free to disregard them because it is not an Urtext.)

It was perfect that Hiroko had the Paderewski edition, because that was what I had been using myself. We opened the score and I gave her a look. “A-sharp,” I said, trying to hide my satisfaction while pointing to the place marked with an arrow below.

Hiroko was shocked. “What? No way!”

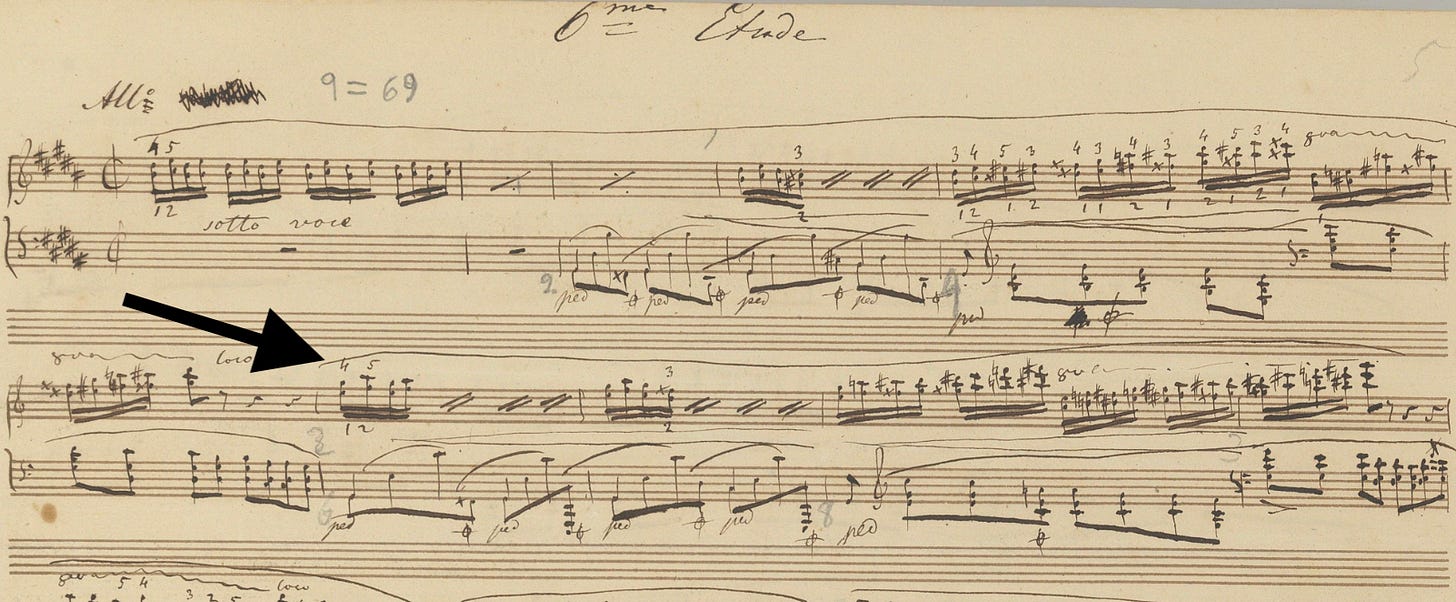

The conversation continued the next day over text. Hiroko sent me recordings — all of which had an A-natural — and scores with both A-natural and A-sharps, including the Fontana fair copy (the closest we could find to an autograph) with an A-sharp.

Right after listening to Maurizio Pollini play A-naturals on my iPhone, I stumbled into a chance meeting with concert pianist Cathal Breslin who had the Henle edition of the Chopin études on his iPad. (True story: We crossed paths at Yamaha Artist Services.) Henle holds some sway as one of the most respected and popular editions: indeed the familiar idea of an “Urtext” owes a lot to Henle.

There were A-sharps in Henle.

I’m sure most conservatory students have either the Henle or Paderewski editions of the Chopin Études on their shelf.

Had the world gone mad? Hiroko and I kept investigating.

Most of our researches were sourced from the IMSLP page, which has the closest thing to an autograph, a fair copy by Julian Fontana, with A-sharp twelve times in a row.

The Carl Mikuli edition is significant because Mikuli studied with Chopin himself. Not everyone thinks that Mikuli should be taken as gospel, but, at any rate, the familiar Schirmer “yellow book” Chopin edition from the turn of the previous century is Mikuli. Mikuli has A-natural twelve times in a row.

One of my favorite musicians is Ignaz Friedman, whose small collection of early solo piano records includes a famous recording of the Chopin étude in thirds. Friedman also prepared an edition of the études that contains much interesting commentary.

(Years ago, when I took a lesson with the late great Robert Helps, he pulled out the Friedman edition of the études, which in that era was very hard to find. Generally Helps was enthusiastic about this edition, especially about Friedman’s personal and at times unexpected fingerings.)

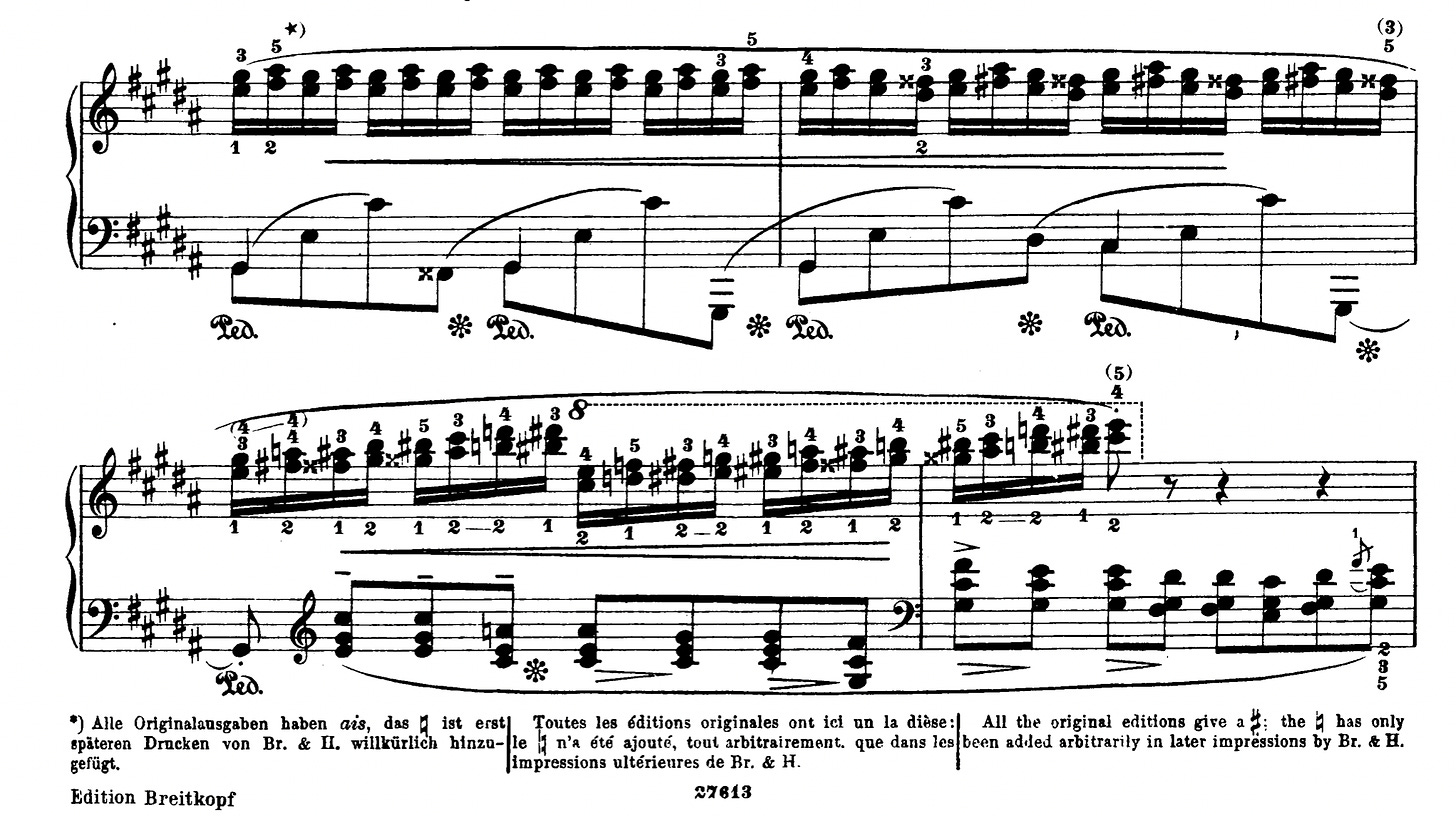

Ignaz Friedman’s edition has the A-sharp. Amusingly, Friedman himself plays A-natural on his famous record, so his barbed comment “All the original editions give A-sharp, the natural has only been added arbitrarily in later impressions” is contradictory.

The Jan Ekier/Polish National Urtext edition (which I believe is respected as one of the best for modern musicologists) says, “Most arguments suggest that Chopin forgot the accidentals, but the version with A-sharp cannot be completely excluded.”

Who plays the A-sharp? So far, we’ve found Geza Anda, Shura Cherkassky, Irene Scharer, Frederic Chiu, and Renana Gutman.

There are other discrepancies in the repertoire that are well-known and discussed — speaking of A-sharp and A-natural, there’s a bar in Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier” sonata that is the topic of hot debate — but as far as Hiroko and I know, this Chopin detail is under the radar.

It remains completely bizarre that the Henle and Paderewski editions have A-sharps (with no editorial comment) while all the most famous and critically acclaimed records (Lhévinne, Pollini, Ashkenazy, Backhaus, Cortot, Cziffra etc.) have A-natural.

We’ve been asking around and everyone gives a blank look or says, “I'd never noticed this!”

I tagged a few major pianists on Twitter and Stephen Hough gave an amusing response. “It's not that Chopin was sloppy but that his 'creation as improvisation' led him (left him free) to change his mind. I would do whichever one you prefer. Maybe alternate sharps and nats. like Feux Follets? (Not!)”

Sonically, both readings work. Everything from the start of the piece through the variant moment is essentially on a G-sharp pedal point, and any pedal point automatically allows for all sorts of diverse color.

Maybe I’m changing over to A-natural, my personal jury is still out. However, looking at the autograph, it does seem (to both Hiroko and myself, anyway) that the composer meant what he wrote. A-sharp appears twelve times for two bars and then Chopin cancels it in the next bar.

Admittedly, if you are committed to the A-natural, subtle clues indicate how Chopin (or Fontana) might have made a mistake: 1) There are repeat signs, so he’s working fast. 2) If it’s a typo, it’s a typo by omission, which is the easiest kind of typo to make.

We will never know for sure. But I like to think that this a unique situation where the guild of elite pianists have brazenly changed one of Chopin’s pitches almost in secret. Again, I look to my hero Ignaz Friedman: Tell the world they should play A-sharp, but when it’s time to make a record for the ages, play A-natural.

Thanks to Neal Kurz, Matthew Guerrieri, Timo Andres, and Yegor Shevtsov for lively discussion of the variant. In particular, Kurz and Andres helped locate those who play A-Sharp.

Jed Distler in Gramophone: “Chopin’s Études: a deep dive into the best recordings.” Distler, an expert, showcases many performances I don’t know. It was interesting to discover to Distler’s no. 1 pick, Juana Zayas from 1983, a great record to be sure.

YouTube compendium by “gullivior”: 30 Pianists play the Chopin étude in thirds. One of the commenters discusses the discrepancy, which is the only place I’ve seen this topic mentioned online. “Interestingly, they all play the A's natural in bars 7-8 where most editions don't cancel the key signature's A#.” Of course the commenter isn’t right, the very first performance by Geza Anda has A-sharp, followed by Shura Cherkassky and Irene Scharer in the same video.

After listening to all 30 pianists in gullivor’s upload, Hiroko pointed out that Ignacy Jan Paderewski himself plays A-naturals, contradicting the Paderewski edition. She also found another discrepancy later on in the étude: E-natural versus E-flat in the left hand. (See arrow below.) We will have to save that investigation for another time…

How strange the change from major to minor - a wonderful, Talmudic dig.

As a casual observer, It seems like A sharp makes more sense., though A is a nice contrast.

My adapted reference for a story like this in the guitar world would be the 12 Villa-Lobos Etudes. I tried to play them unsuccessfully for many years before taking a lesson with Jonathan Leathwood who pointed out that the popular printed edition (Esching) I was using was full of errors (on every page), omissions, and insensitive typeface. Villa-Lobos' own readily available handwritten 1928 manuscripts tell you everything you need to know with absolute visual coherence and a profound understanding of the instrument for which they were composed.