Over the holiday I met Philadelphia concert pianist Dynasty Battles.

Battles is interested in new and old music. The well-produced video of Ted Hearne’s Study Buddy is fabulous.

George Walker is finally entering the repertoire, including now a live performance of the first Walker Piano Sonata by Battles.

I’m also intrigued that Battles is improvising on Beethoven and Schubert in concert. H’mm! I’ll be keeping my eye on what’s happening with this fresh artist.

Sorry to hear that Zita Carno has passed. The New York Times obit by Richard Sandomir is a good read. (Gift link.)

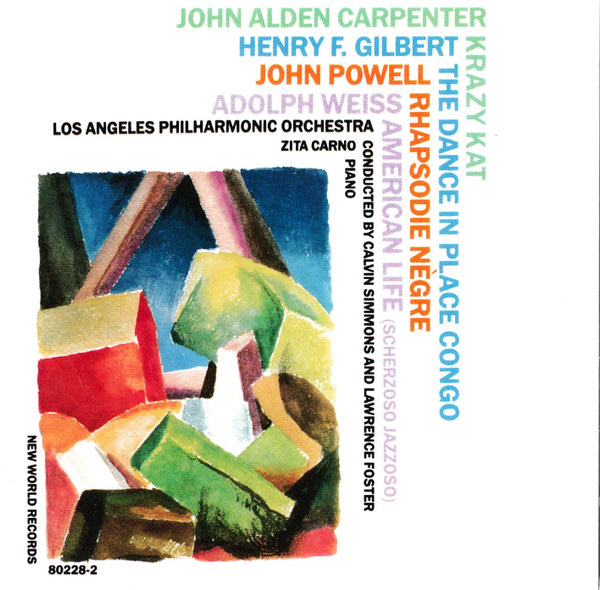

I’ve been aware of Carno ever since reading J.C. Thomas’s Chasin’ the Trane in high school, where Carno has a cameo when showing John Coltrane her transcription of the tenor solo on “Blue Train.” Somewhere in those young years I also got the 1977 New World LP of early “jazzy” concert trivia featuring Carno playing the solo part on various now-forgotten symphonic pieces that pre-date Rhapsody in Blue.

A pianist who was in the Coltrane book but also played with the L.A. Philharmonic? That juxtaposition was intriguing, and definitely made an impression.

Yesterday I posted about an odd, unheralded moment of textual variance in a famous Chopin étude.

The C minor prelude also has a controversial note, for bar three could end with either E-natural or E-flat in the melody: see arrow below. Those who say, “It is certainly E-flat!” base this assertion on a penciled note supposedly made by Chopin himself on a student’s score.

I have mostly heard E-flat over the years, and I think I would play E-flat myself, but some people like E-natural. Important variation sets based on this prelude by Sergei Rachmaninoff and Ferruccio Busoni both feature the E-natural.

On YouTube a scrolling score exists video for a John Ogdon recording of the Busoni Chopin variations. (Typically for Busoni, the topic is a bit confusing, for there are at least three versions of the Busoni Chopin variations and two of them are wildly different, but the version played by Ogdon featured below is the one I know and love best.)

The first variation features ghostly triadic harmonies conjured from Busoni’s personal library of unsettling effects; later variations include en carillon (bells) and a Chopin-esqe waltz of the most morbid kind. The final toccata briefly screams out a major plagal cadence before collapsing in minor. One can almost see the dust.

It’s a phenomenal piece, truly one of my favorite sets of variations.

The “popular” Busoni remains his reasonably straight transcriptions of Bach organ and violin music for piano, including a major recital staple, the Bach-Busoni Chaconne in D minor.

Busoni’s original music is a different kettle of fish, and admittedly, it might not be for everybody. Even when not explicitly referencing another composer, Busoni’s music is usually a “take” on the past, full of ironic references and sly digs, and absolutely best appreciated with a score in hand. A good example of Busoni’s humor are his surprising endings (like that of the variations above), which comment on the preceding argument by abruptly changing key or mode for sardonic effect.

For those wishing to explore further, I recommend without reservation the 3-CD set Busoni: Late Piano Music performed by Marc-André Hamelin. Included are much of Busoni’s finest efforts including the six Sontinas, the group of Elegies, the substantial Toccata, radical transmutations of Bach and Mozart, and truly delectable fancies like the Three Album Leaves and Seven Short Studies for the Cultivation of Polyphonic Playing.

Jazz trivia: Brad Mehldau is also a fan of these outrageous polyphonic studies. Like many others, we both grew up on the terrific 1976 Paul Jacobs LP Piano Etudes by Bartók, Busoni, Messiaen, Stravinsky. (In that set, the Busoni studies are only five in number, not seven like on the Hamelin recording. Again, simply getting Busoni’s prodigious output “the right way up in the box” can be confusing.)

Back to Busoni: Late Piano Music: Marc-André Hamelin is perfect advocate, for Hamelin is more than a bit of a joker himself. Indeed, Hamelin’s own wonderful 12 Études in Minor Keys have many sly digs buried inside the avalanche of impossible piano sound. The line from Busoni to Hamelin is palpable.

Ferruccio Busoni frequently makes me laugh, but at times the extreme textures can take on an authentic lonely grandeur. Busoni’s last piano work, the Prélude et étude en arpèges from 1923, is little-known except to specialists. The Prélude wanders about looking for an exit: Samuel Beckett is perhaps a relevant reference; so perhaps is Vladimir Nabokov. For the Étude, the sound spins out and around. Each desolate and skeletal sonority seems conjured from the most unlikely corner.

I’ve heard other people play this unusual piece, but Hamelin’s recording is unquestionably the best.

Prélude:

Étude:

What a great post! Do you know Busoni’s violin sonatas? I only know the second through an amazing Kremer/Afanassiev recording. Worth checking out!