There are two Paris videos, each half hour in duration, from Studio 104 of Maison de la Radio (ORTF), recorded June 25, 1971.

Ahmad Jamal with Jamil Nasser and Frank Gant

Hampton Hawes with Henry Franklin and Michael Carvin (The “1974” in the video title is incorrect.)

It’s an interesting historical moment to see Jamal and Hawes in action. Sincere thanks to the French production team who did such an excellent job capturing these performances.

1971.

As Bud Powell said, “The Scene Changes.”

Hampton Hawes was born in 1928, Ahmad Jamal in 1930. They made their public breakthroughs in the ‘50s as trio pianists playing standards; both recorded Ellington’s “Just Squeeze Me” in 1955.

That said, I never really think of them in the same breath. Hawes plays a few cute arrangements — any ‘50s cat does — but really he’s one of the greatest bebop pianists. The blowing is the thing. Hawes played with Charlie Parker before Bird was famous and became one of the few who could transfer that hot, disjunct, blues-infused melodic line to the keyboard.

Jamal is more about songful melody and mood. Sure, he plays a few bebop and jazz lines while blowing, but his style is almost like a condensed big-band chart. (Indeed, Gil Evans basically orchestrated Jamal’s trio record “New Rumba” for Miles Davis +19.) This commitment to tight arrangements is one reason Jamal had hit records that reached far outside the core jazz audience, especially “Poinciana” (which I wrote about yesterday).

In terms of their basic approach to the piano, Jamal has more of a European conception than Hawes. Jamal’s technical command is enormous, he shapes every line horizontally and vertically, he can play octave cascades, doubled runs, and other gestures associated with the likes of Liszt and Chopin. Hawes has superb bebop and blues chops but shows little interest in playing “big piano” the way Jamal does.

Neither man stayed still aesthetically. The 1971 performances are completely different than the records that made them famous.

In the 1950s, both Hawes and Jamal spent all their time on the bandstand dealing with traditional tension and release, usually II/V/Is, where you leave and return to the home key through expected chromatic gambits.

In 1971, the II/Vs are pretty much gone, replaced by minor-key modal vamps. The composer credits have also changed: In the ‘50s, they played standards. In 1971, they are playing originals.

The biggest difference seems to be McCoy Tyner. Tyner was a generation younger, born 1938, but the two elders obviously spent time learning the language Tyner played with John Coltrane. (My essay: “McCoy Tyner’s Revolution.”)

Tyner might have been the most important, but on the topic of pianists that influenced everybody, we need to include Bill Evans (who blew open the gates of modality with Kind of Blue) and Herbie Hancock. Jamal even recorded Hancock’s “Dolphin Dance” with Nasser and Gant on The Awakening (1970).

There was certainly something else in the air as well. In the timeline, modal jazz aligns with the Civil Rights Era. For some, playing originals instead of standards became a political act — especially if they were vamp-heavy modal originals. At this 1971 Paris videotaping, it seems important that all members of both trios are black. (In the ‘50’s, Hawes recorded with a lot of white cats, and his regular bassist was Red Mitchell.)

McCoy Tyner’s 1970 album Extensions was released with a cover that would have been absolutely unthinkable a decade earlier.

At the piano, McCoy Tyner raged at the highest pitch, which was a gift for Ahmad Jamal, who became free to do his own kind of raging. At moments on the video he is quite like Tyner: the locked-hand “So What” voicing in parallel movement, pentatonic flurries, and heavy left hand fourth chords. But much of the time he favors stellar virtuoso effects à la Liszt or Chopin (but only if those composers had written groovy modal music).

It must be said that Jamal always has supreme command of the piano and never makes an ugly sound. Tyner himself played hard, and many of his followers simply treated the piano as a percussion instrument, an approach that was frequently required when a loud ‘70s or ‘80s drummer was sharing the bandstand. Jamal never had a drummer who bashed; he could stay lyrical, content to work within the confines of the wood.

It must also be said that the rhythmic side of the music is flawless. Indeed, the unit with Jamil Nasser and Frank Gant is another one of the great trios, and for some is even more important than the earlier group with Israel Crosby and Vernel Fournier. The Awakening has been sampled by hip-hop groups, and that only happens if the beat is right.

(Billy Hart told me about pulling his car to the side of the road to listen to Nasser — when he was still "George Joyner" — play such funky lines on a 50's record with Red Garland on the radio. This would have been when those records were new.)

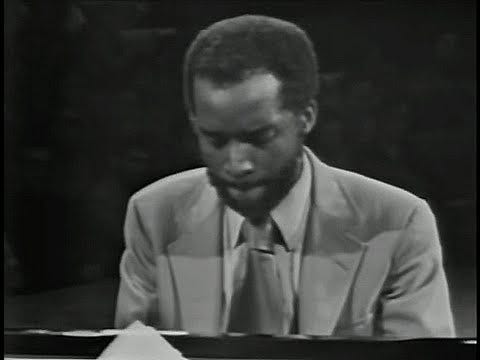

Hawes’s 1971 group with Henry Franklin and Michael Carvin made several records on their substantial European tour. Perhaps Hawes’s basic piano style has changed a bit less than Jamal’s, but there are still Tyner fourth chords and modal drones.

More than most of his ‘50s peers, Hawes was willing to take whatever the rhythm section threw at him. Franklin and Carvin are not subservient to Hawes, at times they are almost leading the charge, and the references are not just to modal jazz but also to free jazz. This collective ethos is in stark contrast to Jamal, who by 1971 had evolved a set of visual cues for Nasser and Gant to follow.

I adore Hampton Hawes but remain mixed about his foray into modal music with vamp-heavy original compositions. For me it is not quite as natural a fit as it is with Jamal. The best LP of Hawes in this manner may be High in the Sky with Leroy Vinnegar and Donald Bailey, which also pairs neatly with Jamal’s The Awakening as it was recorded in 1970. If Jamal plays “Dolphin Dance” and Oliver Nelson’s modal “Stolen Moments,” then Hawes plays his own “Evening Trane” and Burt Bacharach’s “The Look of Love” over a very Tyner-ish vamp.

Hawes was dealing with modal music, but he still was a be-bopper. He bobs and weaves a syncopated line in a way that was never really part of Jamal’s toolkit. The video has it in places, but an easy way to hear Hawes at his modal best is dialing up “Muffin Man” on High in the Sky, where he smokes uptempo F minor 7 for about five minutes straight.

Loren Schoenberg recently posted a blindfold test from Hampton Hawes published October 1970.

Hawes is keeping up with what is current; he praises Hancock, Chick Corea and Joe Zawinul. He says he’s “going to get an electric piano, because it’s definitely going to stay around.”

At the end, he listens to Bud Powell and “Be-bop.” “I still think that music is important…It makes me feel nostalgic.”

Not all of early ‘70s Hawes is equally successful, but he gracefully put away 60’s-era tools like electric piano and modal pedal points for his extraordinary 1976 valediction, At the Piano with Ray Brown and Shelly Manne. The duos with Charlie Haden from the same year are just as wonderful.

Jamal stayed his course, and for the rest of his long life toured with a tight group that put on marvelous concerts full of dramatic tension grounded in immaculate pianism and dynamite rhythm.

Footnotes:

Just learned that Detroiter Frank Gant died July 19, 2021. There were no conventional obits that I can see, but John Pietaro wrote about Gant’s final years for the union paper last fall.

I was once in the same room as Jamil Nasser at a Jimmy Heath event in Flushing. Nasser had a regal presence, and I don’t say that lightly.

Ahmad Jamal himself was similarly regal. When exchanging a few words at a Steinway event, I told him how impressed I was by the Pittsburgh pianists: Mary Lou Williams, Billy Strayhorn, Erroll Garner, Ahmad Jamal…

…Jamal looked me in the eye and said, “Don’t forget Dodo Marmarosa.” Noted.

Henry Franklin played bass on one of the great instrumental hits of all time, Hugh Masekela's "Grazing in the Grass.” Franklin is still around, making music and records in California, as is Michael Carvin, who has taught many of today’s important NYC drummers and released 21st-century albums on Marsalis Music and Motema.

Also perhaps incorrect in the Hawes video is that the first tune is called "Black Forest Blues". It's not the tune "Black Forest" (recorded on blues for bud/ Spanish Steps). The tune in the video is more kind of like "the camel" issued on this group's 'live at Monmartre' record (the inevitable dm vamp), but it's not really that tune either. Wondering if they didn't make this tune up that day.

Incidentally the real "Black forest" is a great tune.. a blues with tasty substitutions, hints of counterpoint, "spanish chords", and powellesque solos. (Hearing the takes with Art Taylor are a revelation).

The group w/ Carvin and Franklin can hit pretty hard w/ the 'bebop" blues too on "Hamps Broad blue acres". (on the 'Monmartre' record) wow..

The drama surrounding this tour of course finds its recounting the penultimate chapters of Hamp's classic memoir..

Readers who enjoyed this can also check out Ahmad Jamal with Marian McPartland:

https://www.npr.org/2017/03/03/518315182/ahmad-jamal-on-piano-jazz