'

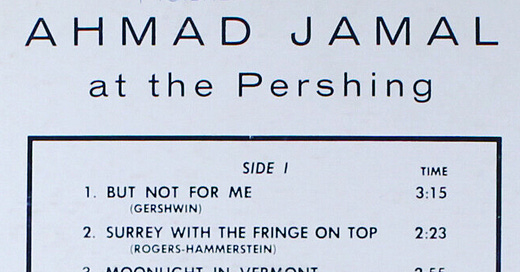

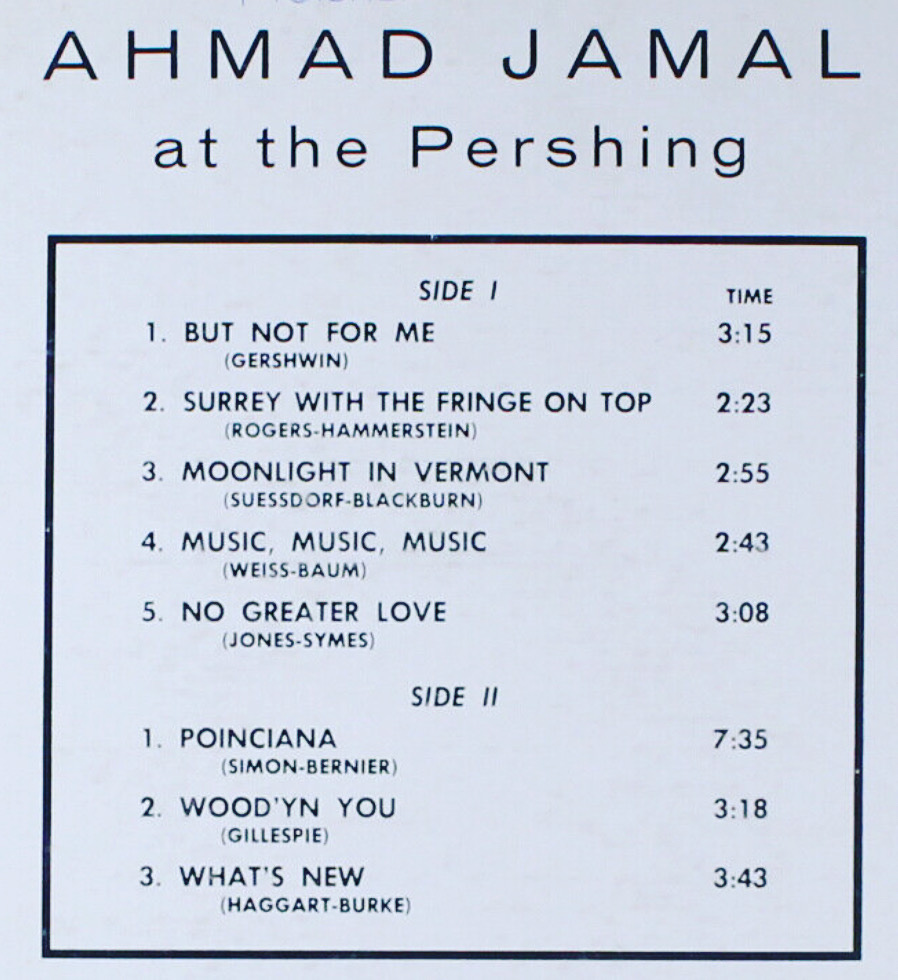

Ahmad Jamal’s famous set with Israel Crosby and Vernel Fournier, At the Pershing: But Not For Me, is a hell of an LP, indisputably one of the greatest records of all time. I’ve heard it my whole life, but on the occasion of Jamal’s passing it was time to listen again with fresh ears.

(For a fascinating historical overview that includes a lot of information I didn’t know, read the dissertation FROM PITTSBURGH TO THE PERSHING: ORCHESTRATION, INTERACTION, AND INFLUENCE IN THE EARLY WORK OF AHMAD JAMAL by Michael Paul Mackey. Wow!)

"But Not for Me"

Gershwin’s lyric starts:

They're writing songs of love, but not for me

In the first seconds at the Pershing, Ahmad Jamal plays:

They're writing songs of love, but not for [blank]

In that [blank], Israel Crosby jumps in with an esoteric bass line that is notably high in register. The history of the piano trio is rewritten at that moment.

Each piano phrase lands with intense swing. Jamal has as much European-style command of the instrument as anybody, but this concert magnificence does not interfere with a greasy beat.

Vernel Fournier is playing the ride cymbal with a brush. According to Hyland Harris, it is not a conventional brush fanned out all the way, but one that is choked up to make it a bit thinner, closer to a stick. The firm quasi-bongo beat is played with a cross-stick on the snare plus a high tom. Fournier is tasty but he’s not in the background. The groove is indomitable. At one moment Fournier lets loose with a china crash.

All three instruments are superbly recorded and balanced just so. Jamal left the most space since Count Basie and Thelonious Monk, and his team expands to fill the canvas.

For the final chorus they casually modulate up a fourth. That modulation is sparse, even skeletal, both Jamal and Crosby in a high register, single notes in sixths going up the chromatic. An absolutely unique modulation.

At the end, the penultimate chord — which lasts a long time, the audience starts applauding too soon — is one of the weirdest on any record anywhere. (It seems to be a C-sharp triad over E, without a “normal” D to make it a conventional dominant seventh.)

"The Surrey with the Fringe on Top"

Brisk tempo. The first chorus is only right hand, high in the piano. Throughout the track, Kansas-City style riffs come and go; there’s also something of a Czerny piano etude gone wrong.

Conversation: Fournier plays the hits even when Jamal doesn’t.

Counterpoint: Crosby moves through all sorts of positions and patterns.

A humorous half-time ending concludes the romp.

"Moonlight in Vermont"

It’s time for a sumptuous ballad. While still swinging, the emphasis is now on grand harmony over a pedal point. The first two “A” sections of “Moonlight in Vermont” offer a rare occasion where a standard ballad from the American Songbag has six-bar phrases instead of the standard eight. Guitarist Johnny Smith and Stan Getz had the big hit single with this track a few years earlier, so there’s a good chance that Jamal is responding to Smith/Getz.

Rowan Hudson is posting detailed and accurate transcriptions of famous jazz piano performances to YouTube. His transcription of “Moonlight in Vermont” explains a lot, for example when and why Jamal plays a full chord with a bass note in bottom of the piano vs. upper structures (“rootless voicings”). (The latter leaves more room for Crosby’s big D-flat.)

"Music, Music, Music"

A somewhat silly ditty, made a bit more serious with pianistic tricks like octaves, conventional big chords, and special chords that sound like bells. Jamal credited Erroll Garner as one of his biggest influences — both were from Pittsburgh — and one can hear that side of Jamal in this happy romp. At 1:18, Jamal lets loose with one of the most astounding sequences of runs this side of Art Tatum, a moment that completely reorganizes the emotion of the music.

"No Greater Love"

The opening rhythm on the vamp is familiar, a clave-derived syncopation that must go all the way back to Mother Africa. However, this kind of opening move was not yet a standard gambit for a piano trio.

It was Ahmad Jamal who made it a standard gambit.

During the intro, Fournier is playing brushes on the snare but no high-hat. When Jamal starts the melody, Fournier brings in the hi-hat on two and four, which makes a difference.

At this relaxed tempo, there’s plenty of time to appreciate Crosby’s sound and vibe, both in cut time and walking in four. The notes are long, the pitches are choice, the strut is sexy.

Much of the time, the pianist isn’t improvising. Certainly Jamal must mix it up from night to night, but the general plan is always highly organized. On “No Greater Love” there’s a chorus and a half where Jamal seems to really “blow.” It’s not pure bebop, but a collection of tricks and tips, all done with astonishing rhythmic panache.

His left hand pulses on the off beat, going straight into the engine room with the bass and drums. Jamal had been doing this for a while; it is one of the many details Miles Davis seems to have encouraged Red Garland to copy.

"Poinciana"

By 1958, many jazz artists were taking advantage of the long play LP by releasing longer tracks. However, on side A, all the tracks are short and could have fit on a 78 from a decade earlier.

Side B opens with one of biggest hits in instrumental music — and at seven and a half minutes, one of the longest hits in instrumental music.

Much of American music is the mash-up of African and European cultures. African means drums. In the case at hand that means Vernel Fournier.

The “Poinciana beat” has gone into the annals of drum literature, but Fournier always was quick to point out he basically condensed a New Orleans brass band beat into a drum set. The cymbal off-beat is played by the left hand, the low tom by the right, an orientation that might seem “wrong” at first, but this sticking simply emulates hands of a marching drummer with a bass drum strapped to their chest; in some formations a tiny cymbal is also mounted on top of the bass drum. The player beats the drum with the right and chimes the cymbal with the left.

As the track evolves, Fournier adds and varies the beat, and ends up with the whole second line in play.

The bass part needs to fit the drum part, of course. Israel Crosby gives the right syncopated flavor. The key of D suits the bass, for then the first note of the groove is an open A string. How many tracks before “Poinciana” began with a funky bass line? No harmony above the vamp, but just the bass and drums grooving along? There can't be many, and almost certainly none for piano trio.

In the 1940’s and 1950’s there was a lot of pretty piano on the radio. Not jazz, exactly, not classical music either, but mood music featuring elegant keyboard confectionery. Eddie Heywood, Don Shirley, Frankie Carle, Carmen Cavallaro, Liberace, Roger Williams, Eddy Duchin; there were dozens of others even less familiar today.

All those “mood” cats could play what they played at a high level, but few prioritized rhythm. None of them could have dealt with Israel Crosby and Vernel Fournier.

The point is relevant because the Jamal piano performance on “Poinciana” is closer to mood music than jazz. Jamal doesn’t improvise on this track, and much of the time he phrases his lush chords in a fairly stately and un-syncopated fashion. It’s gorgeous, it’s one of the best things ever, but there is a connection to the then-prevalent mood-music pianists…which is probably why some jazz critics of the era thought Jamal was a cocktail pianist or worse. (Those critics were apparently unable to hear the contribution of Crosby or Fournier.)

Even the song “Poinciana” is basically from the mood-music playbook. A nice and square 1952 video of the popular vocal group the Four Freshman, themselves beloved by “mood” fans, shows that Jamal didn’t do all that much to rethink the 1936 song by Nat Simon with lyrics by Buddy Bernier.

Not that Jamal isn’t grooving on his “Poinciana,” of course. Jamal is always swinging. Incredible rhythm from this piano player on every bar of every record. But a big part of the magic of “Poinciana” is how Jamal plays the song straight over funky bass and drums.

An allied 50’s genre to mood music was “exotica,” harmless bachelor pad appropriations of Latin, Eastern, and African legend, where one went on a something like a “safari” to something like a “Shangri-la.”

“Poinciana,” subtitled “The Song of the Tree,” is right in there on the “exotic” tip, including the fanciful lyrics, where one dreams of romance under distant foliage. (Percy Faith recorded a relevant arrangement of “Poinciana” on 1962’s Exotic Strings.)

Blow, tropic wind

Sing a song through the trees

Trees, sigh to me

Soon my love, I will see

(…)

Poinciana

Somehow I feel the jungle beat

Within me, there grows a rhythmic, savage beat

The lyrics even have the phrase “jungle beat,” recalling Duke Ellington’s early Cotton Club-era hits that were advertised as “jungle music.” Hyland Harris studied with Fournier; Fournier told Hyland that after their hit record came out, Ellington showed up to a Jamal gig in order to listen to Fournier play that deep beat underneath pretty piano harmony.

Ellington was already well along on his project of groovy diaspora mash-ups, but it is easy to keep drawing the thread from Jamal’s “Poinciana” to Ellington’s Far East Suite, Latin American Suite, and Afro-Eurasian Eclipse.

The jazz cats took everything on this LP, soup to nuts. But “Poinciana” was vastly influential on so much music just a step outside of serious improvised jazz. A whole world wouldn’t exist without “Poinciana”: Vince Guaraldi’s “Linus and Lucy.” Ramsey Lewis’s “Hang on Sloopy” or “The In Crowd,” Bob James, Joe Sample, Dave Grusin…

Keith Jarrett’s famous trio with Gary Peacock and Jack Dejohnette mostly played rough and tumble standards. But early on, they broke up the set list with a long gospel stroll through Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child,” and for many fans that gospel Holiday moment was a career highlight. “God Bless the Child” was the Standards Trio’s “Poinciana.”

"Woody 'n' You"

We are back to swing, and an overt tip of the hat to the jazz community. Dizzy Gillespie was a founding father of modernism and"Woody 'n' You" had become a jam-session staple, not that Jamal doesn’t have a jewel-box perfect arrangement on offer.

When I interviewed Cedar Walton, this piece came up in conversation.

Cedar Walton: I really lean toward trying to have my version of that piece, especially standards: the impossible devotion to either re-harmonizing or putting something in a piece that makes it my version.

Ethan Iverson: Does some of that perspective come from Ahmad Jamal?

CW: Oh, sure. I can’t imagine a piano player in their right mind not checking him out. Yeah, of course. Jamal had a mystique. You weren’t around when he had these really tremendous, successful recordings like Live at the Pershing.

Speaking of “Woody’n You,” Dizzy Gillespie said he got a check for $80,000 because of the tremendous success of Jamal’s record.

"What's New?"

Bassist Bob Haggart wrote “What’s New,” meaning it is one of the few famous standards written by one of the cats. Most people play the song in C, but Jamal puts it in G. Billy Hart taught me that one can hear future soul and R’nB coming out of the trio’s repeated note bass vamp (aligned with just a hint of backbeat from Fournier).

It’s a moody and glamorous performance, full of pianistic fairy dust. The album ends on a solemn minor seventh, and it is time to turn the LP over and listen again.

You nailed it. When I heard about his passing, I played “Live At The Pershing” for three days, still not finished with absorbing the treasures. Your analysis is adding to my searching. I love the spaces, things not played, on “But Not For Me”, and the move from 4 to 3 and back on “Moonlight....”. It really is perfection throughout the entire two CD album!

But Poinciana would not be what it is without its accompaniment of cutlery and waitresses. 8 minutes of supreme artistry, anyone? "Nah, I'm having the chicken".