“King Porter Stomp” is still is heard in popular culture, a Jelly Roll Morton piece arranged by Fletcher Henderson and recorded by Benny Goodman in 1935. Henderson’s arrangement proved to be the template for countless big band charts since. (These saxophone voicings, which owe something to Henderson’s associate Don Redman, have proven to be eternally hip.)

Bunny Berigan, trumpet, Jack Lacey, trombone, Gene Krupa, drums, and the leader on licorice stick. Just such a great record! Thills and chills!

Fletcher Henderson makes the history books as 1) an arranger for Goodman and 2) for leading his own band that featured Louis Armstrong and Coleman Hawkins. However, he was also yet other brilliant keyboard artist in age blessed with pianistic genius. The denizens of Harlem circa 1920 were moving ragtime and blues into jazz, and “The Unknown Blues” (or “Unknown Blues”) is a fast piece of novelty ragtime that pairs well with other side of Black Swan 2026, namely James P. Johnson’s very first recording, the classic “Harlem Strut.”

In terms of being preserved for posterity, this 1921 platter is about as early as solo jazz piano gets. America was still a segregated society, this was the era of “race records,” and the name of the label, Black Swan, indicates to the consumer that this is going to be black music with a groove. (The Wikipedia entry on Black Swan is interesting: the forerunner, Pace Records, was co-founded by “The Father of the Blues,” W.C. Handy, while Fletcher Henderson was the house pianist for the new venture Black Swan.)

As fabulous as this ancient acoustic record is, can you imagine the earth-shattering effect of Henderson sitting down to play “The Unknown Blues” in front of you in 1921?

“Chimes Blues” from 1923 goes a bit deeper into a blues bag. Big shouting piano playing, the 12-bar folk form, a bit of boogie-woogie (although they didn’t call it that yet, Pinetop Smith’s trope-namer would come in 1928), a chaotic double-time chorus, and modulating up a fourth about halfway through the track. This last effect goes back to ragtime, called a “trio” in Joplin’s sheet music, and would vanish from the timeline pretty soon, although “King Porter Stomp” for Goodman above has a trio. (In the Henderson arrangement, they get to the trio early on and stay there.)

Henderson is not really improvising, nor were these scores written down. As with the early ‘20s records of Jelly Roll Morton and James P. Johnson, these sounds are in that liminal space that occupies so much music from all cultures and eras, where a final product is polished through intensive private practice.

Still, does it make sense to consider Henderson’s early solos in the context of scores? Joplin and other ragtime composers is a given. For the blues it is harder to find precedence, although W.C. Handy published simple blues pieces in the teens, some with second strain up a fourth (like “Beale St. Blues”)—and Henderson worked directly with Handy in the early ‘20s in Harlem including at what would become Black Swan records.

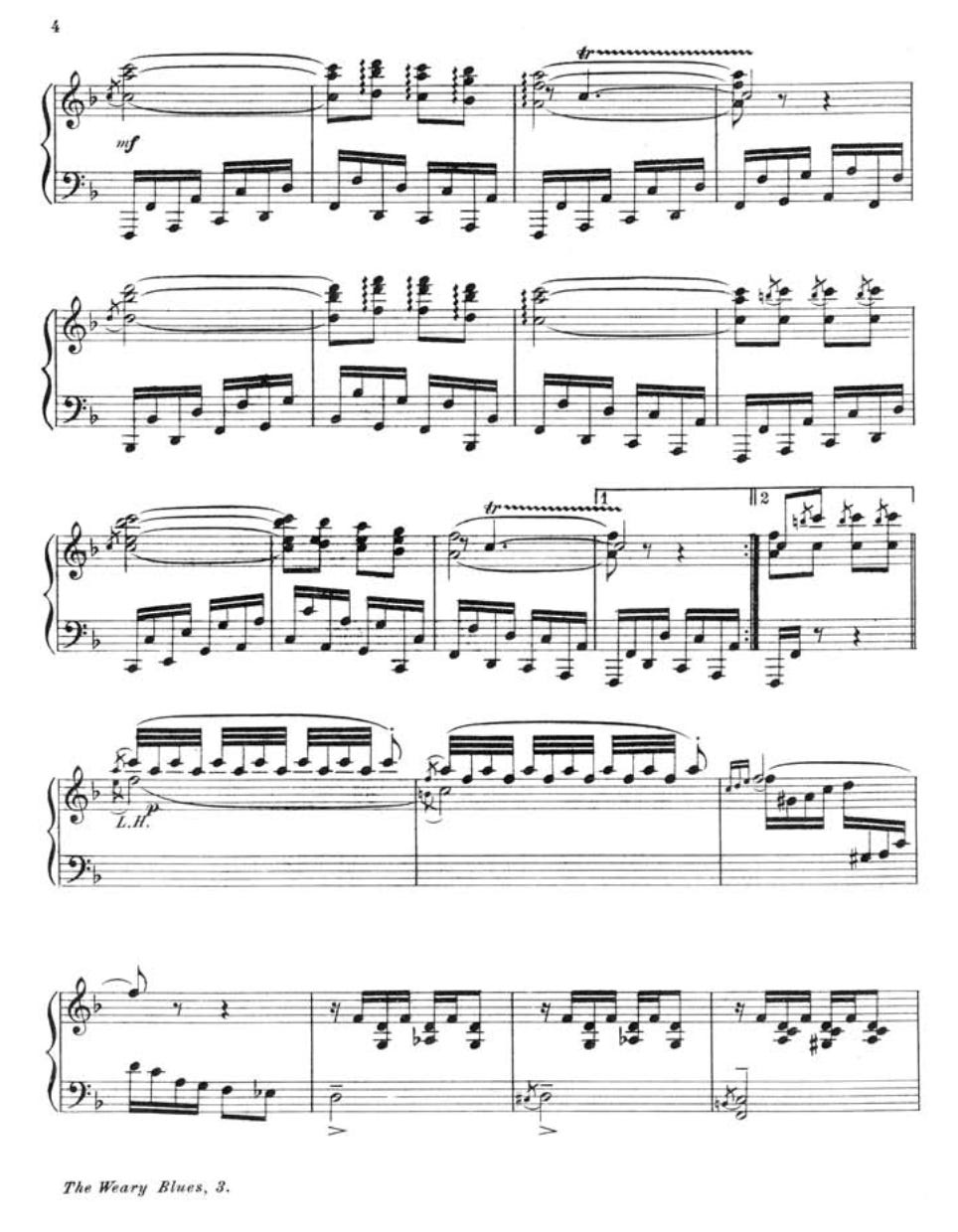

Intriguingly, Artie Matthews’s “Weary Blues” from 1914 has blues and boogie figurations with a trio up a fourth. (Matthews taught Frank Foster, and Gershwin made a piano roll of Matthews’s Pastime Rag No. 3 in 1916 with a hint of swing feel.)

Perhaps one way to view Henderson’s “Chimes Blues” is as a virtuoso amplification of Joplin + Handy + Matthews (and others lost to the mists of history) not unlike Chopin’s mazurkas and Liszt’s Hungarian rhapsodies. An interesting thought experiment: Given the choice to record their own performances, would Chopin or Liszt have written so many notes on the page?

Earl Hines also recorded a tremendous “Chimes in Blues” a few years later in 1928. While both pieces feature chiming effects at the top of the keyboard, they share no melodic material. However—in a move that remains surprising by modern standards—Hines also has a later strain that leaves the 12-bar form.

Hines is improvising a bit more than Henderson, and the phrasing is looser, but this track (and the rest of the wonderful solo ‘28 Hines material) still feels fairly set. Hines would take more risks later on.

Previously on TT: Fletcher Hendersons’s “Queer Notions” as name-checked by Louis Armstrong…

TT 321: Louis Armstrong Lists Some Records in 1934

(This is the first of three more posts in the wake of my article “Louis Armstrong’s Last Word” in The Nation.)

I feel like Earl Hines is due for a reappraisal in contemporary terms

Thinking about arranging some of this for brass quintet, particularly the Matthews.