TT 568: RIP Richie Beirach

This was not a surprise, for the pianist had been battling health issues for some time. I always grouped Richie Beirach with Hal Galper and Jim McNeely, and now they are all gone within a year of each other. Below is a fresh edit of comments originally posted in 2024 for a fundraiser intended to help Beirach defray medical expenses.

In the early 1960’s, there was McCoy Tyner, then there was Herbie Hancock. Hot on their heels by 1967 or so were Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett.

By the early 70’s, people were looking around to see who was next, and many would have voted for Richie Beirach, who was born in 1947 and just beginning to appear on major gigs and records. Beirach had not just the fire and a brilliant piano technique, but also a dissonant harmonic approach that embraced the modernist ethos of 20th-century composers like Bela Bartók, Igor Stravinsky, and Arnold Schoenberg.

Tyner, Hancock, Corea, and Jarrett knew those composers as well, but they usually only visited those lands for novelty effect. Beirach took up residence at the modernist encampment, and this made his style fresh and distinctive. When playing with bass and drums, his biggest influence seemed to be one specific track by Chick Corea, “The Brain,” which featured a twelve-tone melody and presto furioso intervallic piano blowing. This approach was lean and almost ahead of the beat, although when playing a solo standard, Beirach could certainly conjure a romantic moment inspired by his friend and mentor Bill Evans. Still, his associates affectionally called him “Code,” for he was always up for some additional math. Certainly nobody did more with a slash chord: For a while there in the ‘70s, Richie Beirach could have almost copyrighted E triad over C in the bass.

Beirach’s lifelong musical partner was saxophonist David Liebman, and together they explored the post-Coltrane, post-acoustic Miles, and post-Bill Evans continuum with drive and finesse. The 1986 album Quest II on Storyville is one of my favorites from this prodigiously productive collaboration. This was the first time Liebman and Beirach recorded with Ron McClure and Billy Hart, a quartet that would go on to be a working unit for decades.

The album opens with Beirach’s composition “Gargoyles.”

“Gargoyles” starts as a ballad, something like jazz, but unusually sophisticated in harmonic construction. A unison angular line for piano and sax fragments into nothingness, then a duo of bass and piano commence free exploration. It’s a rhapsodic fantasy of strangeness—one of Beirach’s best idioms—and concludes with truly virtuosic piano tremolos. The music transforms into backbeat vamp for the burning sax solo; Jabali is large and in charge. While the genres move around there’s no uncomfortable shifting of gears, the track is a unified statement. Peak 1986!

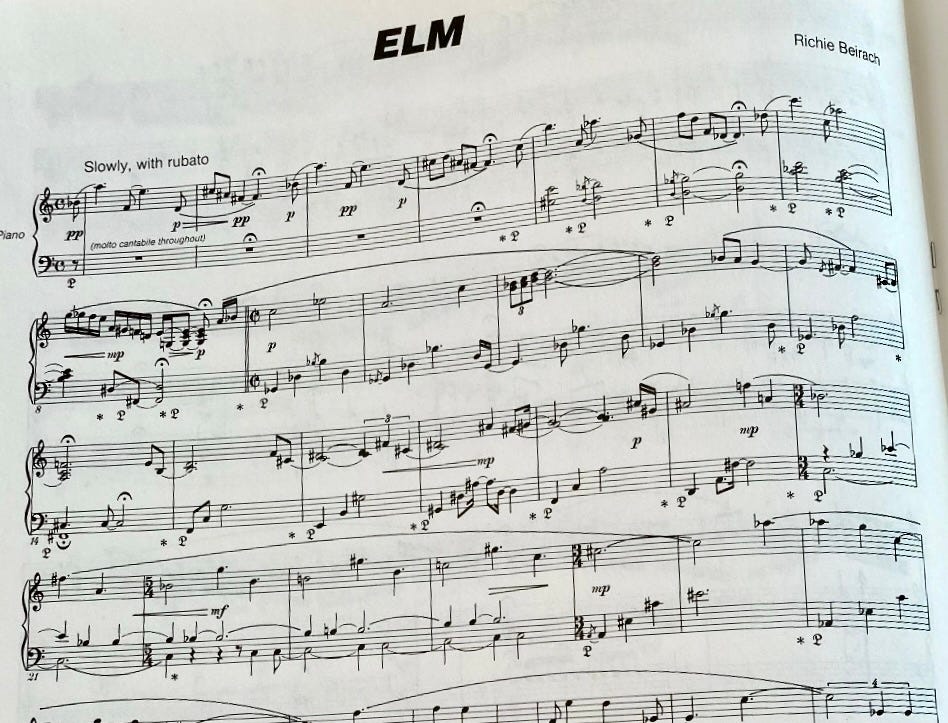

Another version of “Gargoyles” is on The Duo Live, made in the same era as Quest II, one of the many recordings of Beirach and Liebman together alone onstage. The album was transcribed accurately in full by Bill Dobbins. Issuing the recording with a score was an unprecedented and decidedly helpful event, for I played through it as a teenager and learned many things! Decades later, I looked at the score again, and was appalled at how much I had stolen straight from this Beirach transcription.

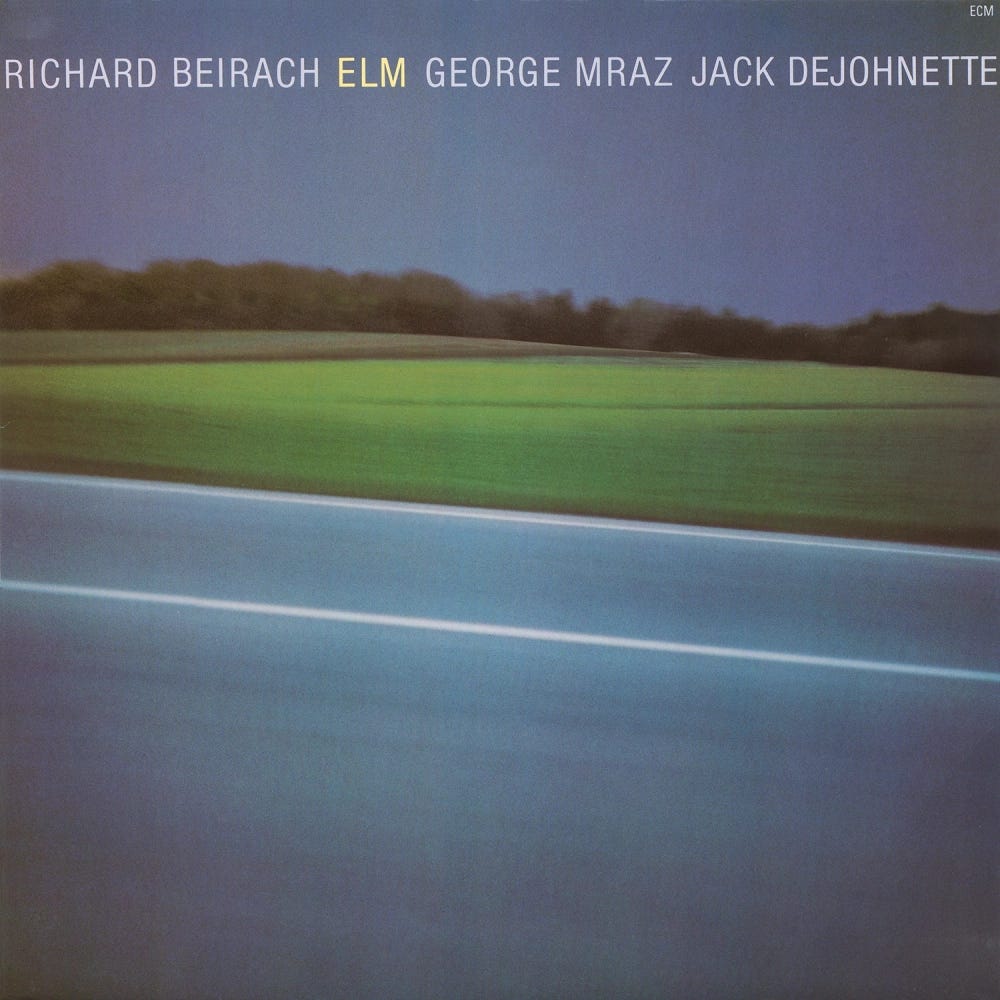

Beirach’s own piece “Elm” might be as close as his generation of jazzers came to generating an anthem. A great version is on The Duo Live, and it is also the title track of an important ECM album from 1979. Elm is probably the best Beirach trio session, worthy of comparison with Chick Corea’s Now He Sings, Now He Sobs. The complex chromatic interplay between Beirach, George Mraz and Jack DeJohnette was cutting edge at the time and still sounds good today. “Pendulum,” a fierce swinger heard on both Elm and Quest II, is another Beirach tune that helps define an idiom.

I’m not sure if the name “Richie Beirach” ever resonated with a larger public, but the serious pianists know. Kenny Kirkland’s style was unthinkable without Beirach’s influence, and at the Village Vanguard this past December, Kenny Barron programmed “Elm” and told the audience that Richie Beirach was one of his favorites.

I went to Richie's house a few years ago to hear his story about working with ECM / Manfred Eicher for a series of 51 short films I made about ECM's history from 1969 (or 1961, actually) to 2019. It's here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NrC8C210u2I Manfred has seen it, too, and called me to say it was fine to publish this.

A wonderful appreciation. Thank you, Ethan. Liebman's Lookout Farm (1974) with Bierach in the ensemble, was my first taste. It was a perfect hand-holding intro to the what's next. It brought new delights.