TT 564: Back to School: Comment on Clave

one for students of swing

(This post is for those that study with me at NEC. The dropbox of my educational materials is here.)

Tootie Heath told me something about the rhythmic structure of swinging jazz: “Not too many ‘ons,’ not too many ‘offs.’”

We were listening to Kenny Clarke play with Miles Davis on “Walkin’” at the time, and Tootie was talking about Clarkes’s left hand on the snare drum (which he also called “coughing”) or Horace Silver comping at the piano. Both players were placing their hits on a mixture of on and off the beat.

In a lesson, Charles McPherson told me something related: “The accents in a jazz phrase should sound like popcorn beginning to pop in a pressure cooker.”

In other words, the syncopations in a bebop melodic line should have a staggered, unexpected feel.

Billy Hart told me over twenty years ago, “I hear the clave in all of jazz.”

At first I had no idea what Billy meant, but over time I began to understand a little bit of what he might be saying.

NOTE: I don’t know much about Cuban music, so take everything I’m about to say with a grain of salt! After reading my post, talk to somebody who actually understands this stuff!! The Latin Police are ferocious, even worse than the Jazz Police, please don’t put me on a watchlist!!!

There are two standard Cuban clave patterns, the son clave and the rumba clave. They are traditionally played on wooden dowels originally fashioned from ship-building pegs; both can be spoken like this: “How are you? I’m fine.”

“How are you?” is the three-side, “I’m fine” is the two-side.

The claves are not interchangeable, but either can exist with either phrase first (for the duration of a piece). “How are you? I’m fine” is the 3:2 clave, “I’m fine, how are you?” is the 2:3 clave.

The only difference between son and rumba is whether the “you” falls on 4 or the and of 4; in this post I’ll only be addressing the son clave.

Classic jazz is in 4/4, and for a long time the accompaniment was basically in straight quarter notes, like the oom-pah of Scott Joplin’s ragtime. Sure, there was remarkable rhythmic sophistication in the way the top and bottom interacted, but the bottom was reasonably predictable and even.

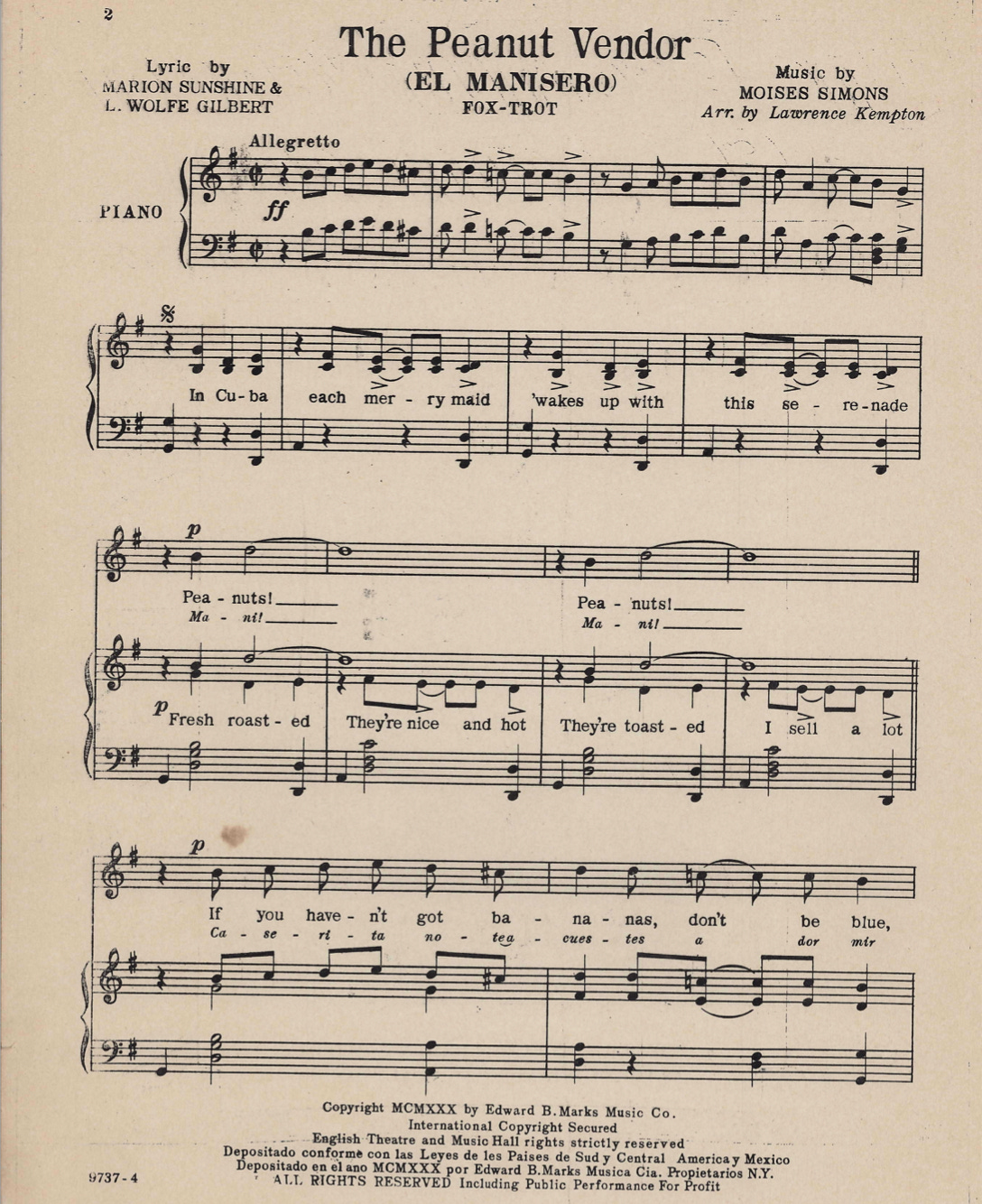

I speculate something began to change in about 1930, when Cuban music had a notable coup in America with “The Peanut Vendor,” sung by Antonio Machin, accompanied by Don Azpiazú & His Havana Casino Orchestra. Both the 78 and the piano/vocal sheet music sold in record-breaking numbers.

“The Peanut Vendor” uses the 2/3 son clave. “I’m fine, how are you?” The clave is prominent on the Azpiazú record, and the melody fits the clave smoothly.

Both Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington recorded “The Peanut Vendor” within a year or two of Azpiazú’s smash hit. (Chris Washburne has a helpful chapter on “Peanut Vendor” as played by Armstrong, Ellington, and everyone else in his book Latin Jazz: The Other Jazz.)

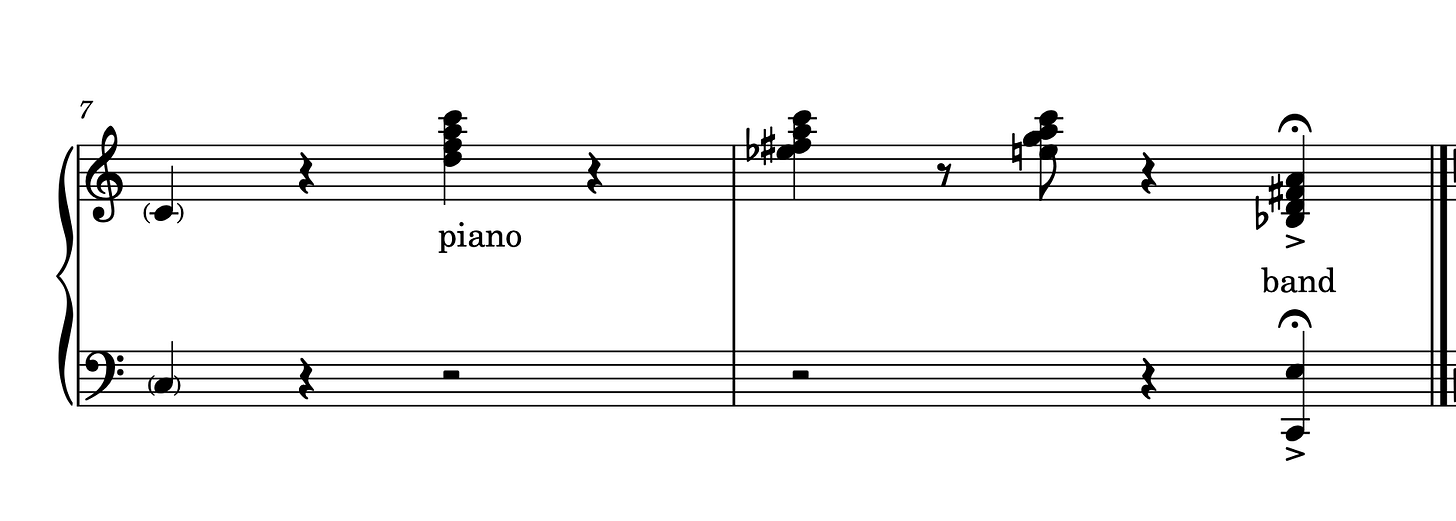

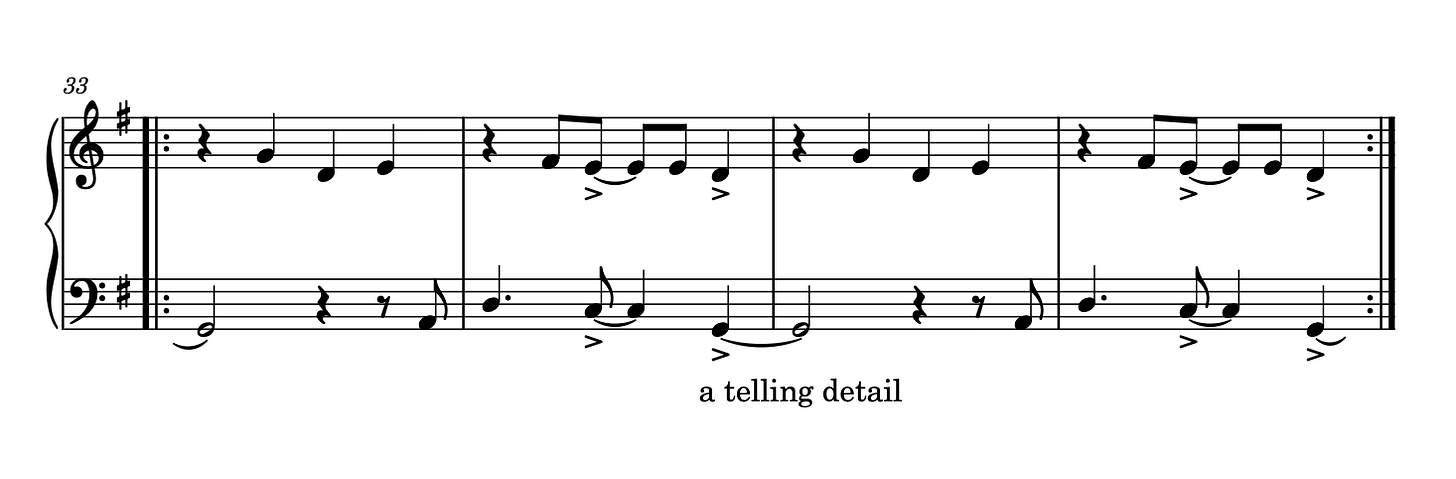

The three side of the son clave (“How are you?”) is the money side, and in fact, on its own, the three side is “The Universal Rhythm,” heard in many cultures of the world. However, it is the Cuban version that sustains that the third articulation into the next bar, a telling detail.

Azpiazú is pretty mellow, a gringo can follow the beat on that big hit “The Peanut Vendor” pretty easily. But in more advanced Cuban arrangements, that big sustained accent on four can foreshadow the future harmony and “reverse” the whole layout of the harmonic progression. At this point, the gringos start to get a worried look on their face.

There’s a nice big band version of “The Peanut Vendor” (as “El Manicero”) by Bebo Valdés on Cuban Dance Party (1959). The bass part on the opening riff emphasizes the sustained syncopated beat 4.

Dizzy Gillespie did a lot to put the Cuban aesthetic into jazz with Chano Pozo. But, again, Billy Hart told me, “I hear the clave in all of jazz.” Meaning: swinging jazz. Not “Manteca” or “A Night in Tunisia,” but “Now’s the time” and “Hot House.”

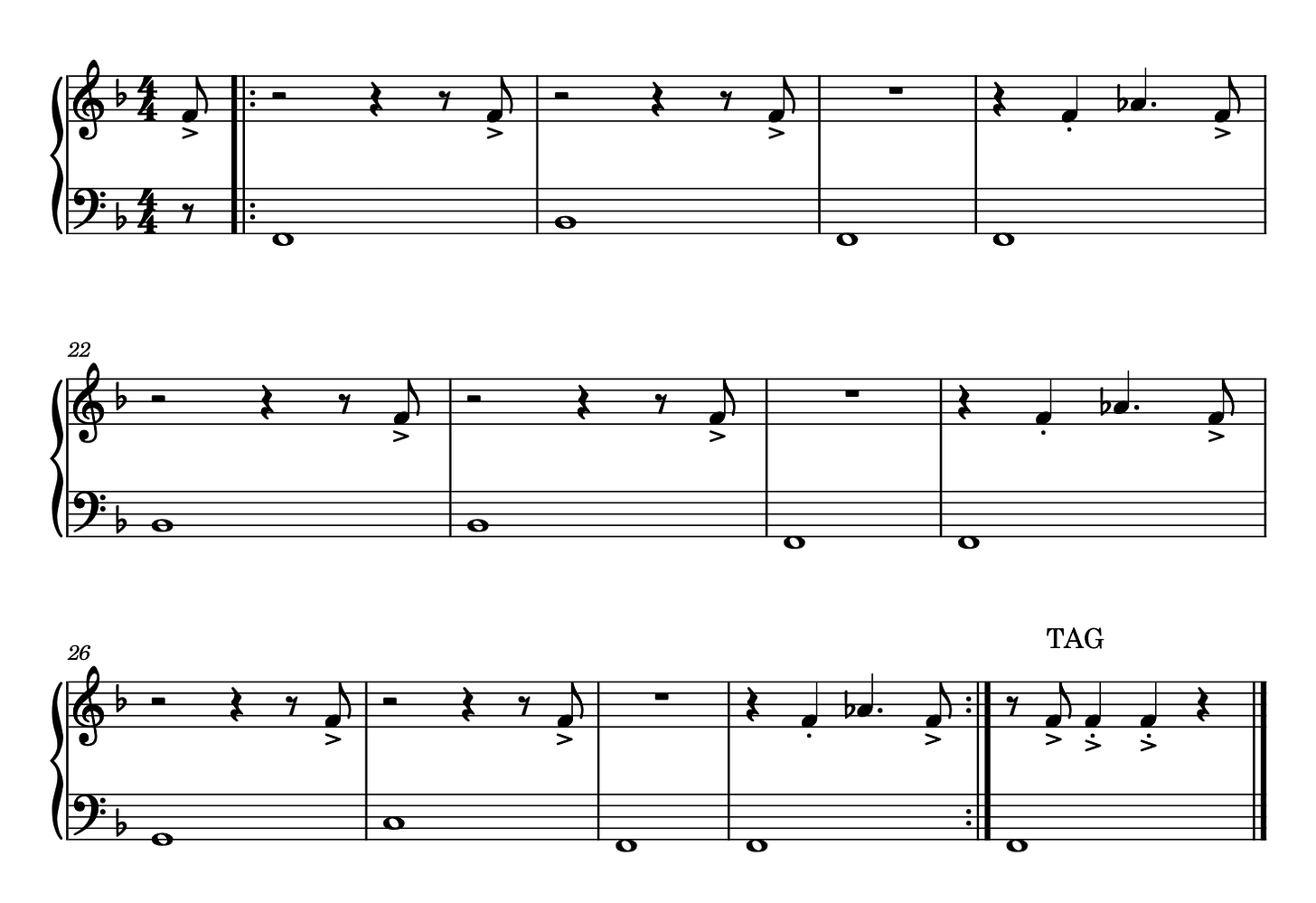

One of the most popular endings for a swinging jazz number is the ending Billy Strayhorn wrote for “Take the A Train.” Is it a stretch to say “Take the A Train” ends in clave? I won’t force the point, but it is definitely wrong—absolutely wrong—to move the final attack to beat one of the next bar. The last hit has to be on four. The grammar is only correct if the rhythm is immutable.

The familiar Count Basie ending has a similar rhythmic structure, 2:3 son clave concluding on a sustained beat 4. (Actually, I don’t know the first time Basie did this on record—if you know, drop it in the comments.)

Scott Joplin ends his rags squarely on beat 3. Jelly Roll Morton and James P. Johnson end their 1923 piano solos squarely on beat 1 or 3. The Louis Armstrong Hot Fives and Sevens generally end on beat 1 or 3. I think these 2:3 clave jazz endings of “Take the A-Train” and Count Basie only entered the repertoire after Cuban music turned up on record and on the radio in the late 1920s.

There’s a certain kind of intensity to the syncopation of Cuban music due to the immutability of the clave. The three side lands off-kilter, while the two side is a momentary repose. Yet…the off-kilter becomes grounded. It’s no longer syncopation, but simply “the way it is.” And that kind of “the way it is” intensity is the point, that “the way it is” intensity would inform swinging modern jazz melodies and accompaniment in the 1940s and 1950s and beyond. Again, this was seemingly influenced by all the Cuban music pouring into America. The mambo replaced the fox-trot as the latest dance craze, and the all the big bands started playing “latin” numbers.

In our interview, Henry Threadgill explained:

Mario Bauza told me about the wrassling match when the modern jazz guys came in and tried to play with the Latin cats in 40’s. The clave and the swing wouldn’t mix! Bauza said that Charlie Parker could bring the music together, but as soon as Bird stopped the wrassling match would begin again. Mario said that not even Diz or Dexter Gordon could do that, but Charlie Parker could.

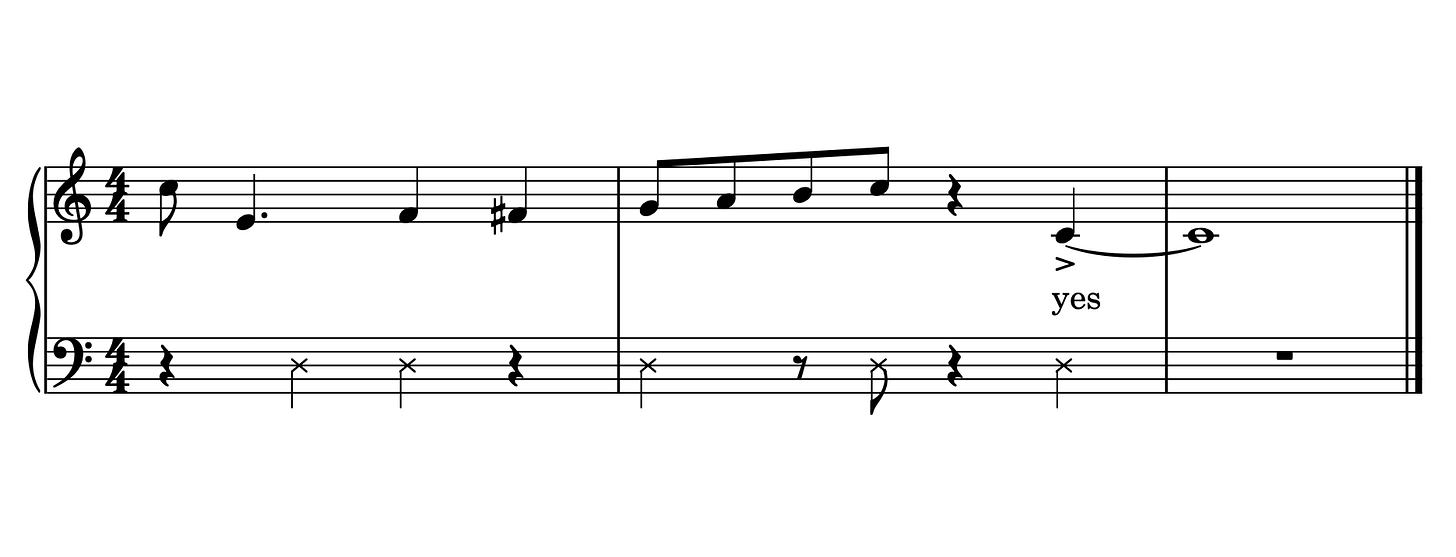

There’s no doubt that Bird was the ultimate master of syncopation and that Bird was influenced by Cuban music. The last 8 bars of “Moose the Mooche” are arguably in 3:2 son clave…

But I am not sure if looking for something literal like a clave inside a Bird line is that important, as long as you acknowledge that the genres are interacting. Tootie Heath’s comment was pretty casual: “Not too many ‘ons,’ not too many ‘offs.’” Kenny Clarke broke up the time with unexpected bass drum accents: They called them “bombs,” but perhaps you could call them Cuban. And what about the syncopations in Paul Chambers’s walking line? Check that bass part on the bridge on “Milestones,” is that a tumbao?

Classic jazz is indebted to European harmony, but in the end the masters just took bits and pieces of that old world language in order to fashion the new. Same thing with Cuban music, the heavy jazz cats could just borrow a pinch of intense seasoning and roll with it. It happened again in the 1960s when the jazzers appropriated Brazilian music, although this time it was more obvious because the music was ready for an expanded even-eighth repertoire. (Horace Silver even called his original composition “Song for My Father” a bossa nova.)

To be clear, Cuban music and swinging jazz are not really the same bag, and in fact, some of the lesser swingers had success with Cuban idioms in the ‘40s and ‘50s: Stan Kenton’s “The Peanut Vendor” (with a notably creative Pete Rugolo chart) was one of his biggest hits, George Shearing excelled at the mambo mood, Cal Tjader and Vince Guaraldi were thought leaders for a certain kind of fresh sound.

Kenton, Shearing, Tjader, and Guaraldi are all great musicians of course, I’m calling them “lesser swingers” in comparison to Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Wynton Kelly, etc., and even then only because Kenton, Shearing, Tjader, and Guaraldi did record plenty of lightly swinging music.

In a video interview, Don Alias talks about needing a piano player in Boston in the early 1960s. He found Chick Corea. “Chick didn’t know a damn thing about latin music. He had Bill Evans cold and had Wynton Kelly chops, but knew nothing of latin music. We had him come by the pad, and played him all the Cal Tjader records with Lonnie Hewitt and Vince Guaraldi. Chick took those records home, and literally the next day, on the gig, this cat was playing the montuno.” (I’m paraphrasing slightly for written grammar, it is heard at 6’45’’ in the interview.)

This anecdote showcases the impurity of American music. “Chick Corea learned Cuban music from playing along with Vince Guaraldi” is a true sentence. (I’m not suggesting Corea stopped with Guaraldi, of course, there’s no doubt that Corea kept studying.)

Back to serious swing. John Coltrane’s tenor solo with Red Garland, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones on “Straight, No Chaser” from Miles Davis’s Milestones is profound, a Mount Olympus of swing. At one point, Garland and Jones play pre-planned hits behind Trane. It goes for two choruses, and then there’s a tag.

The tag sounds Cuban to me, the way certain unison breaks reset the undulating syncopation before the next verse.

Intensely rhythmic music is hard to talk about. It goes by so fast and it is so understated, and the heroes rarely explain. I’m no hero, but I have been around enough heroes to know there are plenty of rules and regulations only understood by the elite.

When Billy Hart talked to me about this moment of Red Garland and Philly Joe Jones on “Straight, No Chaser,” Jabali said the tag is essential; that if you don’t play the tag, then the previous two choruses are invalid. That’s the word he used: “invalid.” His eyes darkened as his voice lowered in pitch while gaining in volume. “If you don’t play the tag, the previous two choruses are invalid.”

The kind of intensity Jabali projected when talking about “Straight, No Chaser” is present on any swinging jazz records from the ‘50s, especially if the drummers are people like Max Roach, Kenny Clarke, Roy Haynes, Art Blakey, Philly Joe Jones, Art Taylor, and Jimmy Cobb. It was a certain way of life, a certain way of looking at the repertoire.

My tentative conclusion is that there is never a single syncopation, that all the upbeats and staggered rhythms are part of sentences, just like in Cuban music. I think that’s part of what Jabali means when he says, “I hear the clave in all of jazz.”

Footnote one: Ragtime was often notated in 2/4, so was the tango, so was the bossa, the Wikipedia entry on clave has 2/4 as well. Horace Silver’s original lead sheet to “Song for My Father” is in 2/4. I’ve never seen a chart in 2/4 on a conventional jazz gig, so 4/4 is my default, but there is something intriguing about 2/4…

Footnote two: Cuban tropes are all over the work of Thelonious Monk, and eventually Jerry González’s clave homage to Monk with the Fort Apache Band would make sense.

On the 1954 Monk trio record of “Bye-Ya” with Gary Mapp and Art Blakey, someone uncredited is playing the son clave with claves (I guess, it’s a sharp wooden sound at least). Wikipedia says it is Garvin Masseaux on “shaker”—something I read for the first time today.

I’m a bit doubtful, for Masseaux is on some great records sounding excellent and this “Bye-ya” clave performance seems almost arrhythmic! Indeed, I always assumed that clave part was just gamely offered up by a non-musician friend who dropped by the studio, someone like Gary Mapp, a Brooklyn cop who is on no other records and repeatedly plays wrong bass notes on “Bye-Ya.” At any rate, it is a wonderful track.

Ethan Iverson Teaching PDFs (link) includes

Original Sheet Music of Two Dozen Jazz Standards

Theory of Harmony

Bird is the Word

Doodlin’

Core Repertoire

21 Cramer Studies Taught by Beethoven

Bud Powell Trifecta

Trane ’n Me (by Andrew White)

New Orleans second line music is infused with clave as is the city's R&B (eg. Professor Longhair's Go to the Mardi Gras). Also, the famous Bo Diddley (Mississippi) beat is rumba clave as is Buddy Holley's (Texas) Not Fade Away.

Every summer Sunday in Central Park at the lake near Bow Bridge there is a pan Latin rumba. It originated in the 1970s by Puerto Ricans. After the Mariel boatlift the Cubans who came to New Jersey basically told the Puerto Ricans they were doing it wrong and there was a negotiation. I learned that the core rumberos in the park are Lucumi who originated rumba on the docks of Mantanzas. They disassembled shipping crates and turned them into drums and used the pegs Ethan reference as clave sticks. [I may be incorrect about some of this and welcome correction by those more knowledgeable than I].

The clave was pretty explicit whenever Ray Barretto played congas on all those Prestige dates with the Red Garland Trio, Gene Ammons, et.al.