In the next issue of The Atlantic, Matthew Aucoin has been given space for a proper think piece, “Do You Actually Know What Classical Music Is? Does Anyone?” Aucoin is using this mainstream platform to reach out to those with comparatively little experience, and succeeds in making many salient points about the value of notation.

As a (terrific) composer, Aucoin lays down the law with every bar of every piece. Perhaps his article would be even stronger if Aucoin dispensed with throat-clearing and simply admitted that he traffics in the sublime. Through notation, a composer controls progression and unity through substantial swaths of time. This kind of sublime cannot be achieved any other way.

Much of the 21st-century discourse surrounding classical music in America emits a vague sense of apologetic desperation. Other places might be different—it’s hard to imagine an article called “Do You Actually Know What Classical Music Is?” being published in Berlin, London, or Moscow—but in America, the genre struggles unhappily between the pressures of indifference and elitism.

In Hearing Secret Harmonies by Anthony Powell, a character remarks, “Firmness, in any sphere, is ultimately the only thing anyone respects.”

Three recent releases by American artists treat the genre of classical music with requisite firmness. It is honest music for the sake of music. Despite fashion and despite academia, the makers are doing what they think is right, and for the right reasons.

Tom Myron is not self-taught, exactly. In conversation Myron will tell you exactly who he studied with and exactly where he learned what. His aesthetic masters are an eclectic bunch: British and Russian symphonists like Walton and Shostakovich; film and TV scores of the golden era; rock, jazz, Sérgio Mendes. At one moment, he will discourse on Samuel Barber; the next on Luciano Berio.

Yet there is a curiously naive quality to Myron, a boy in the woods left to learn orchestral graces on his own. If he likes it, he uses it. As a result, it all works. A Myron score is deft, tuneful, easy to read, and fun to listen to. In the end, this naive boy is a consummate professional.

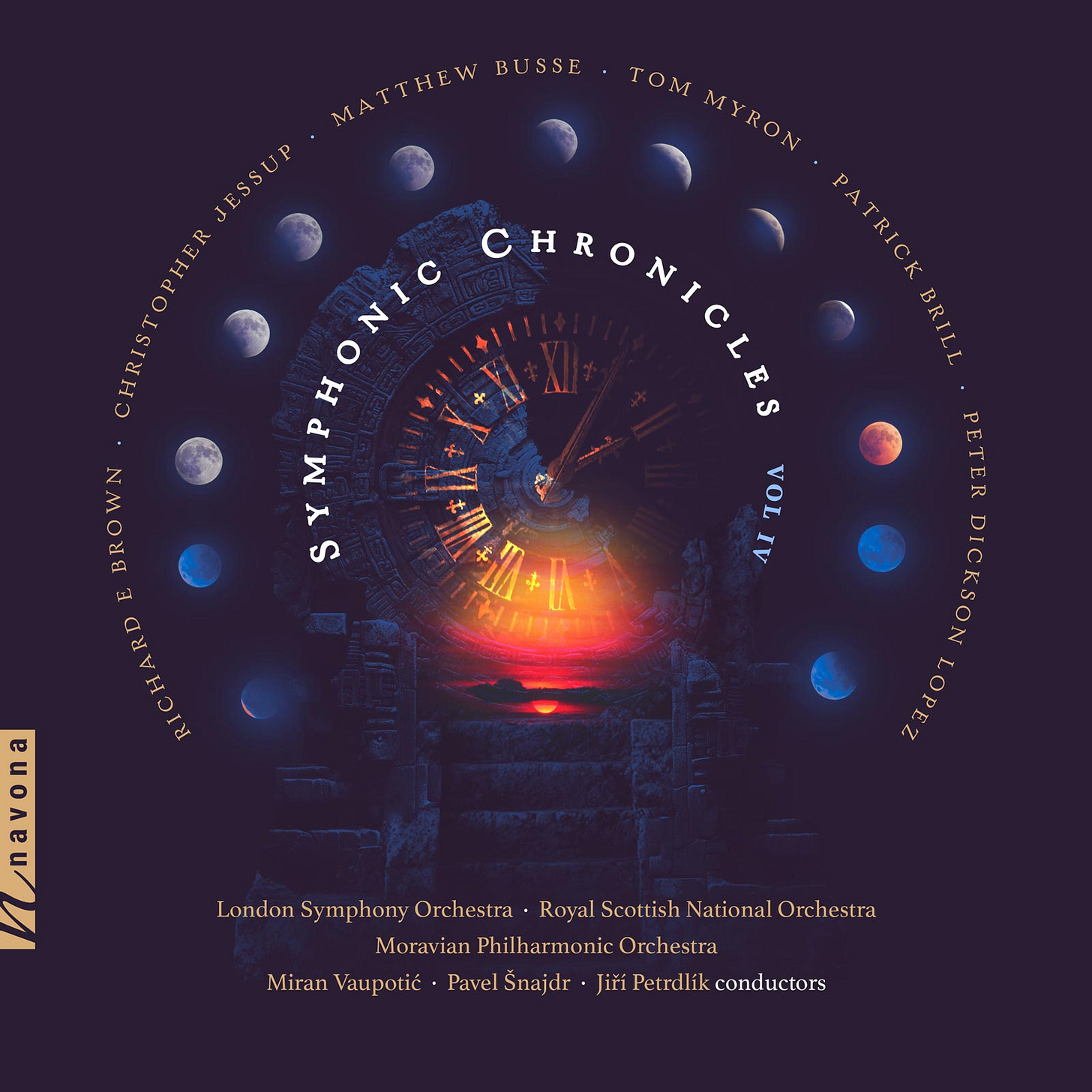

A substantial catalog is being assembled. The latest release came out last week, “Monhegan Sunrise,” part of Symphonic Chronicles Vol. IV on Navona Records. At first blush, the work is conservative, but Myron’s flute flurries color just outside the lines and the overall narrative is unpredictable. Each moment is perfectly composed for the orchestra.

In the press release, Myron explains,

For me the idea of “pushing boundaries” in composing is a little cliched at this point. In fact, I’m classically trained, but I don’t really consider myself to be a classical musician, at least as I’ve come to understand the term over the span of a 35 year career. I’m a creative musician who expresses himself through writing as opposed to performing, but I’m always working very closely with performers.

As both a composer bringing original work to orchestras, and as an arranger working with other artists to create symphonic settings for their music, I work to create collaborative connections with everyone involved. I’m very conscious of approaching the resources that I have to work with in ways that most effectively realize the goals of a particular project. That can mean realizing my own vision of a natural environment that is alive with kinetic energy, like in “Monhegan Sunrise” and “Mystic Whaler.” It can also mean creating settings in which a group or a solo artist that has never worked with an orchestra before feels their work being supported and energized by a rock-solid symphonic setting.

In both cases I am fully embracing the expectations and traditions of symphonic writing, because these are its strengths. There is no better way to earn the trust of musicians, solo artists and audiences than to deploy the resources of the full orchestra in the most exciting, colorful and cinematic ways possible, all in the service of an unforgettable musical experience.

Christopher O’Riley has had a substantial career as a major virtuoso. In addition to playing standard repertoire, his original arrangements of Radiohead were something of mainstream hit (it turns out that “Let Down” works particularly well as a piano solo). There have also been significant collaborations with James Galway, Pablo Ziegler, Matt Haimovitz, and puppeteer Basil Twist.

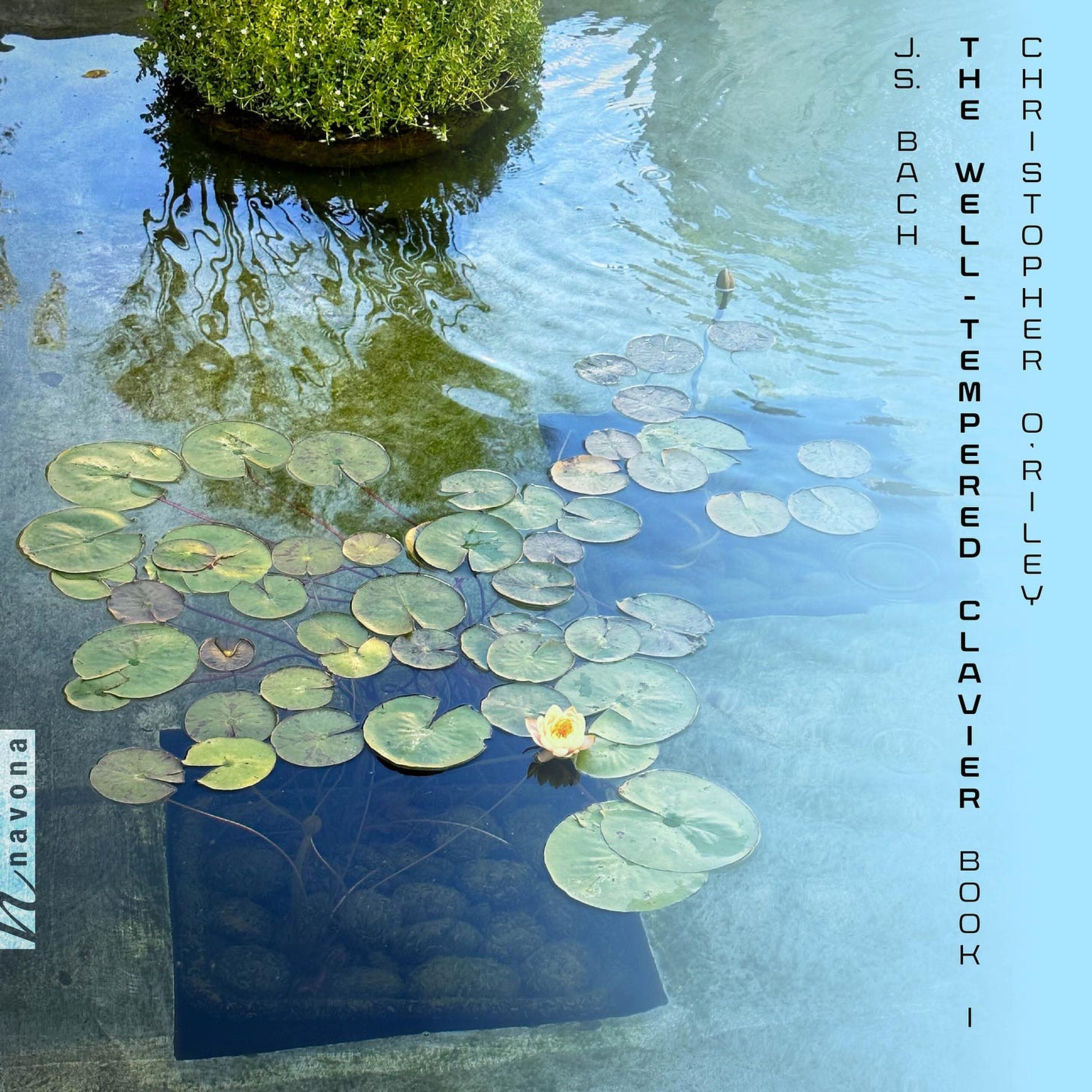

In recent years O’Riley has undertaken a somewhat lonely and uncommercial journey, delving deep into J.S. Bach and producing a traversal of the first book of The Well-Tempered Clavier for Navona Records.

O’Riley’s conception of this familiar music is unexpected, with the fugues proving to be particularly good. In the hands of most pianists, the sleek and homophonic preludes make more sense than the contrapuntal fugues. However, O’Riley’s fugues are dense, strange, and vulnerable, with vast amounts of rubato and endlessly variegated articulation. If the fugue is in four voices, four different voices mutter and intone in four different dimensions. At times the texture is a bit lumpy, almost as if the pieces were being improvised on the spot, and the tension provokes the listener into staying glued to the argument, listening almost worriedly for each new fugal entry. “Whatever will Bach do next?”

At the beginning of The Glass Bead Game, Hermann Hesse lays out “The Age of the Feuilleton,” a time when society has no sense of higher culture. (And this was long before TikTok!)

Hesse writes:

…during the very period of its decay and seeming capitulation by the artists, professors, and feature writers, it entered into a phase of intense alertness and self-examination. The medium of this change lay in the consciences of a few individuals. Even during the heyday of the feuilleton there were everywhere individuals and small groups who had resolved to remain faithful to true culture and to devote all their energies to preserving for the future a core of good tradition, discipline, method, and intellectual rigor. We are today ignorant of many details, but in general the process of self-examination, reflection, and conscious resistance to decline seems to have centered mostly in two groups. The cultural conscience of scholars found refuge in the investigations and didactic methods of the history of music, for this discipline was just reaching its height at that time, and even in the midst of the feuilleton world two famous seminaries fostered an exemplary methodology, characterized by care and thoroughness. Moreover, as if destiny wished to smile comfortingly upon this tiny, brave cohort, at this saddest of times there took place that glorious miracle which was in itself pure chance, but which gave the effect of a divine corroboration: the rediscovery of eleven manuscripts of Johann Sebastian Bach, which had been in the keeping of his son Friedemann.

Bach is perhaps a way for the star pianist to “remain faithful to true culture and to devote all their energies to preserving for the future a core of good tradition, discipline, method, and intellectual rigor.” Reportedly a second volume of O’Riley investigation, WTC 2, is in the works.

Johnny Gandelsman is a brilliant and multi-talented violinist. He’s part of the ace string quartet Brooklyn Rider; an associate of Yo-Ya Ma in the Silk Road Project; the creator of In a Circle Records (which has amassed a significant catalog under his stewardship); he even writes movie scores for Ken Burns. Last year Gandelsman received the MacArthur “genius” grant.

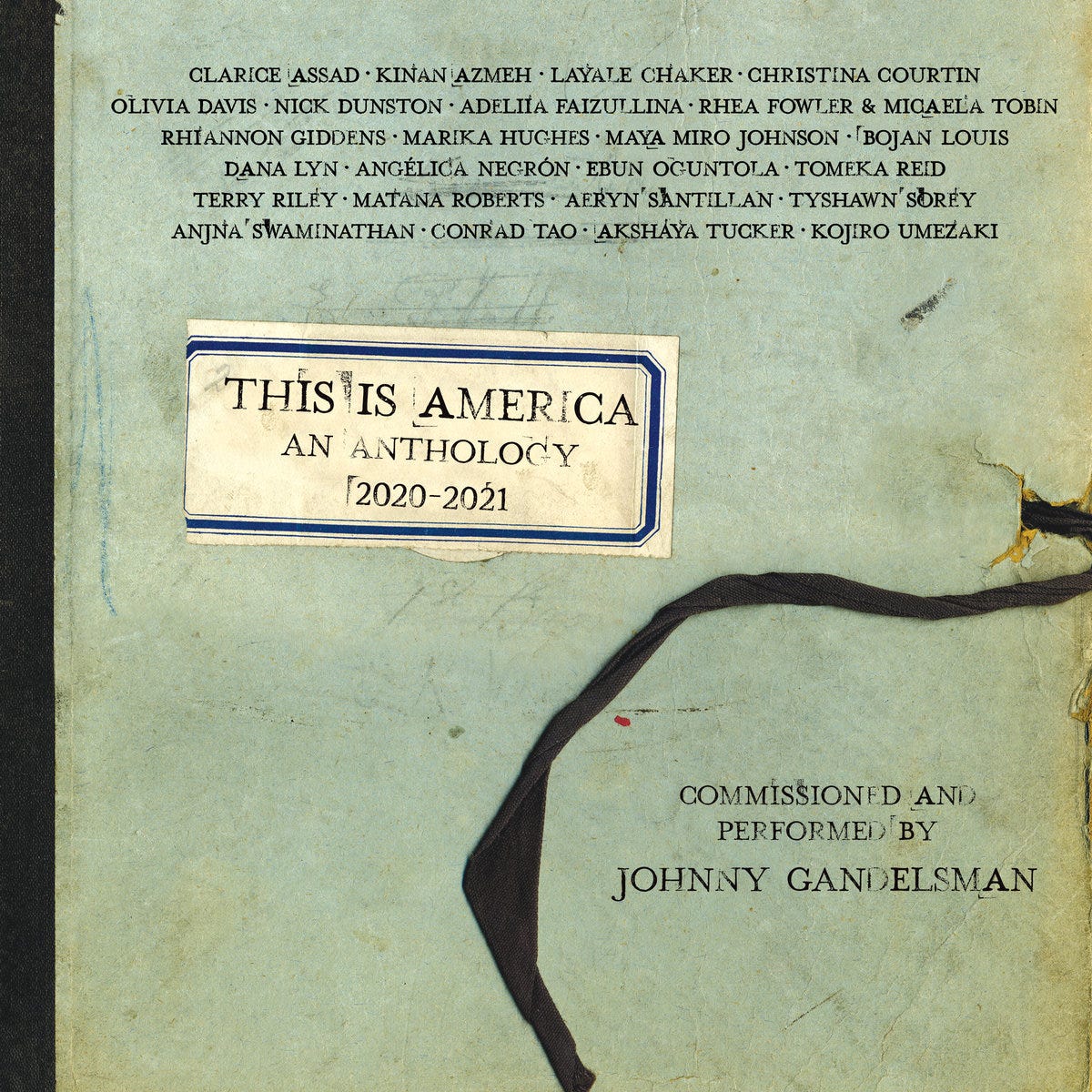

The pandemic begat This Is America - An Anthology 2020-2021, an epic solo project featuring 25 composers contributing 33 tracks over the course of 3 CDs. Many of the composers are comparatively unknown, and some of them had never written violin music before. In a few cases Gandelsman plays along with voices or electronics; at times he wields a guitar or 5-string violin.

The old saw “I have the strength of ten because my heart is pure” applies to Gandelsman in this heroic role as commissioner and performer. Naturally, not everything is equally engaging, but it is all worth hearing, especially since Gandelsman has the measure of all the styles, from bluegrass melody to atonal frenzy.

Some of the tropes of Aucoin’s article “Do You Actually Know What Classical Music Is? Does Anyone?” are relevant, for Gandelsman is deliberately trying not to make a traditional classical music album. However, this scorn of authority plays to the main strength of American culture: Anything is allowed in almost any circumstance as long as it is authentic and feels good.

As the 21st-century rolls on, musicians who can multi-task traditions in a genuine manner will become even more prevalent and essential. This Is America - An Anthology 2020-2021 is a significant entry in the progress towards a better future, where all the streams are understood and honored.

Four notably striking pieces:

Olivia Davis, Steeped in three movements. “Impromptu” offers a whispery hum with key melodic notes jumping out of the texture. (This must be just the devil to play.) “Moto Perpetuo” is gritty and streetwise. “Cadenza” shimmers in a half-light of tremolo and sustain. Davis’s harmonic language is dissonant but engaging; I will keep my eye out for more from this composer.

Terry Riley, Barbary Coast 1955 for 5-string violin (the fifth string is a low C, and those low notes naturally sound like a viola). Riley is famous for early minimalist works, especially In C, but in recent years the elder Riley has been writing chromatic tunes. Barbary Coast 1955 seems to start almost as a lyrical and sentimental tango in G minor. The first development section goes far afield into high harmonics, and the piece gradually radiates out through several other styles.

Dana Lyn, A Current Took Her Away. Lyn is a good violinist herself (I’ve heard her with Hank Roberts) and the double stops accompanying the pretty tune obviously lay well on the instrument. The rhetoric makes perfect sense, and the piece builds to an effective and passionate climax.

Tyshawn Sorey, For Courtney Bryan. Sorey is the first musician in history to share equally valid credentials as jazz drummer and concert composer. For Courtney Bryan begins with an evocative chromatic lament; later contrasting sections offer burning lines not far from today’s modern jazz. This impressive work could well enter the active violin repertoire.

Further listening:

Tom Myron’s Violin Concerto no. 2 is sensational.

Two favorite Christopher O’Riley CDs include an early record of the first Roger Sessions sonata—a great piece, superbly played—and Stravinsky’s piano arrangement of Apollon Musagète, where O’Riley adds some appropriate touches not found in the Stravinsky original. (I believe O’Riley was the first to treat Apollon Musagète as a work suitable for a concert pianist.)

Johnny Gandelsman has recorded two solo Bach recitals. The violin music is expectedly great; the cello music (played on violin) is unique.

I love everything you write Ethan, but as a jazz elder, and classical novice, I extra appreciate your forays into classical/notated music. I'll locate, and order all of these CDs. (I recently met with my financial advisor, and told him I need to add a new expense category to my budget: Ethan's Recommendations.)

This is a great post. I was going to skip the Aucoin article, but now I know I need to read it.

And Tom is a fantastic composer, arranger, and orchestrator. I've learned so much from him, both in conversation and from listening to and studying the scores of his music.