All the jazz piano greats could play a basic swing style for dancing. They could do this solo, without a rhythm section.

The left hand is stride, an oom-pah derived from Scott Joplin and other ragtime composers — although the original oom-pah goes back to the European march: there are even more pianistic examples in Chopin, Liszt, Brahms, Schubert and others.

Stride is a bit difficult in the left hand, especially when the tempo gets fast. Playing uptempo Harlem Stride in the manner required for James P. Johnson’s original music (like his famous “Carolina Shout”) is a virtuoso affair. But a slower speed should be manageable for most.

Mid-tempo stride is the gait of the most popular dance in America between 1910 and 1940, the foxtrot.

Foxtrot piano is connected that book of familiar repertoire by Broadway composers like George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, Harold Arlen, and all the rest. Standards. If you can play a foxtrot version of a standard from one of those Broadway composers, you are playing jazz.

James P. Johnson recorded the first jazz version of Cole Porter’s “What Is This Thing Called Love” in 1930. Foxtrot piano! This mid-tempo track is eminently danceable.

Johnson is looking at the published Porter score — he even plays the verse, which is rarely heard today — and changing certain things.

Broadway people don’t have a beat, not really, not compared to the great black jazz musicians. Johnson plays with a stomping beat.

Broadway people don’t know nothin’ of the blues, not really. Johnson adds in syncopations, dissonant grace notes, and shakes, all evocations of the great blues singers.

At a purely pianistic level, Johnson plays most of the melody in octaves and big chords. This is standard practice, for most significant melodies in foxtrot piano are reinforced: If you play for dancers, you need to project through the sweat and smoke of the club, especially in an acoustic situation. (Eventually playing the melody in octaves simply became part of the style, even on a concert stage.)

After James P. Johnson there was Fats Waller, Earl Hines, Mary Lou Williams, Erroll Garner, and so many more. Teddy Wilson was the standard bearer and Art Tatum was the apotheosis.

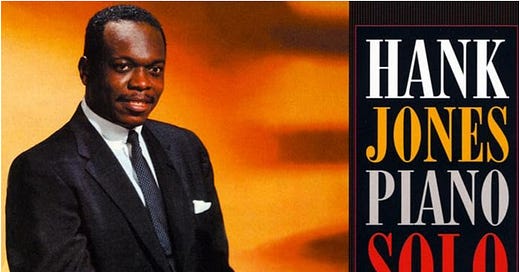

Hank Jones spanned several generations. He was directly inspired by Teddy Wilson and Art Tatum, yet sounded great playing bebop with Charlie Parker and then in a hard-hitting 1970’s trio with Ron Carter and Tony Williams.

There’s no better example of deluxe foxtrot piano than the 1956 Hank Jones record on Savoy, issued both as Have You Met Hank Jones and Solo Piano.

A “Cross Section” page in Down Beat from 1958 is intriguing:

When talking about Fats Waller, Hank Jones says, “The beat’s the thing.” He describes being on the road with Hot Lips Page: “He was blues all the way through.” (The Page group would have only been playing at venues that allowed dancing.)

The set list of the Jones 1956 Savoy session is mostly Broadway standards. As with James P. playing “What Is this Thing Called Love?,” it is the beat and the blues that makes the difference. That black folklore interlaces with the pretty tunes and the result is intoxicating.

Broadway standards are still somehow relevant in American life. Even today, people know those tunes. (Harry Connick and Lady Gaga have done their part.)

Every semester at NEC, students turn up playing old songs like “Body and Soul,” “It Could Happen to You,” and “All the Things You Are.” These student performances are frequently abstract and heavily-improvised with a creative and avant-garde character. The students often start with dissonant meditative chords, seeing “how they feel and where the music takes them,” and then proceed to improvise with a somewhat esoteric and undanceable feel, frequently with lots of left hand counterpoint.

If the student is advanced, I might suggest a couple of thought experiments.

You are part of some major fundraiser, playing for a singer. Backstage you are waiting to go on with some actual stars, including Quentin Tarantino and Michelle Obama. (It doesn’t need to be Tarantino and Obama, I ask the students to pick two famous people who are not musicians, a man and woman, people they admire.) There’s an upright piano in the corner and somehow Tarantino and Obama learn you are a jazz pianist. “Hey, Michelle, you like jazz, right?” “Sure, Quentin, I love jazz.” “Maybe this kid will play us your favorite tune.” “Really? Do you know ‘Body and Soul?’” (or insert whatever standard my student had just played in the lesson). How are you going to play this familiar standard requested by Quentin Tarantino and Michelle Obama?

You are dating someone you really like, and it has gotten to the point where you are invited over to their parent’s house. The Mom and Dad are there, they seem welcoming enough, but of course you still want to make a good impression. Mom says, “I hear you play piano!” and Dad says, “You play jazz, right? I like jazz. Can you play us something? We got the instrument tuned last week!” How are you going to play jazz piano in the home of the parents of the person you are happily dating?

You are on a high-end cruise ship in the middle of nowhere, playing rock music in a band that pays really good. Wynton Marsalis is there, not gigging, but just chilling on the cruise with his wife, the famous violinist Nicola Benedetti. The president of France, Emmanuel Macron — apparently a good classical pianist — is also relaxing on the cruise. One day Wynton finds you at lunch, and says, “You’re the only piano player on the ship. You can play, right? Nicola and Macron want to hear a few tunes. Come with me and let’s play ‘All the Things You Are’ and a blues. I have a piano in my suite; we will take a photo after.” How are you going to play “All the Things You Are” and a blues with Wynton for his famous wife and the president of France?

Foxtrot piano is the answer for all three scenarios! You can survive for a few minutes in these fraught social situations if you can play foxtrot piano.

You can also work in restaurants and rehearse with singers if you can deal with this idiom. We teach lots of esoteric things in jazz school except how to make a living. In certain contexts, adequate foxtrot piano can command a fair wage.

Practicalities aside, I fervently believe being able to play standards in a conventionally danceable fashion will help any student no matter their aesthetic endgame. Perhaps it is sort of like feathering the bass drum. Most of the really swinging drummers can feather the bass drum whether they do it on the gig or not. Likewise, most of the really serious jazz pianists can play some foxtrot piano whether they do it on the gig or not.

I was so happy reading your article. I grew up in a dance academy and we lived above it. We taught Fox trot, cha cha waltz etc. The BEAT defines the style of dance to which it's related. My father was a tap dancer and we all danced and performed. Your point about the deliberate abstractness of the music describes the problem exactly. If I may stretch your point a little bit, when the body can't relate to the music, then it's only the mind. There is nothing wrong with that of course but, if you want to relate, then maybe we should try and start fully relating again.

I've long envied pianists (and guitarists, and to a lesser extent, bassists and drummers) who have the capacity to take advantage of the scenarios you describe. As a woodwind player, I cannot tell you how many times I've wondered what analogs are for us. We're secondary, add ons, for obvious reasons.

When I was a teenager first playing club dates, one of the best pieces of advice I was given was to learn to play "cocktail hour piano," a few songs from the (old) Real Book that could cover dead space while others in the band took a dinner break or something. It did not necessarily make me more money, but it did make me more hireable.

Must be something in the ether... You and Gioia both emphasized the prominence of the dance aspects of the music in your posts this weekend. Important stuff and great scenarios to present to your students, to be sure.