Around 2017 I published about half-a-dozen articles for the online Culture Desk at The New Yorker. Michael Agger was my editor, which was a great experience, although his shocking edit of my Green Book piece became one of my party stories. (I wrote up the anecdote a few months ago.)

Agger certainly helped out with “Deck the Halls with Vince Guaraldi” — which, for the record, is about the only time an editor has accepted my proposed title. (The only other instance was “The Worst Masterpiece: Rhapsody in Blue at 100,” I made the editor agree to the title before writing the piece.)

On Tuesday a certain event triggered a whole sweep of human emotion: I heard “Linus and Lucy” in a coffee shop. A free morning gave me another chance to touch up a few corners on my old essay…

DECK THE HALLS WITH VINCE GUARALDI

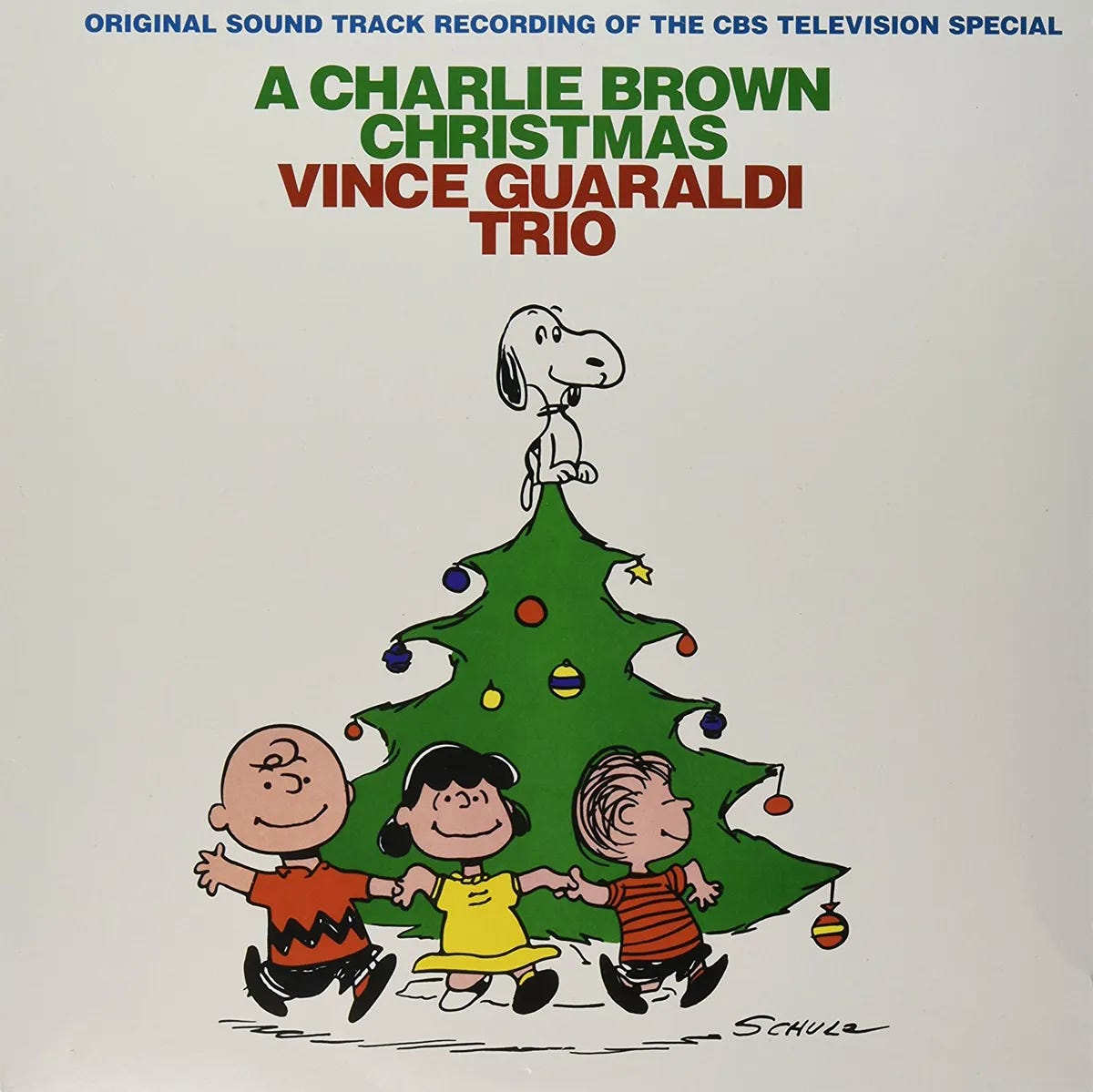

It’s that time of year, and Vince Guaraldi’s contribution to Holiday Muzak remains fresh. Guaraldi’s cover of “O Tannenbaum” is simple and “jazzy”; the slightly bland “Skating” offers rolling thirds in waltz time; “Christmas Time Is Here” is a great song given extra character by a children’s chorus.

Still, there’s no doubt that the headliner is “Linus and Lucy,” one of the most famous piano pieces of all time.

(The name “Linus and Lucy” isn’t as familiar as the sound. Drunken patrons fervently demand of the cocktail pianist: “Play Peanuts!” or “Play Snoopy!” or “Play Charlie Brown!” This is reminiscent of the era when Paul Newman and Robert Redford led many to call a famous Scott Joplin piece “The Sting” instead of “The Entertainer.”)

Vince Guaraldi was a proficient San Francisco jazz musician who worked with Cal Tjader and Stan Getz in the fifties. He lacked the fire of Hampton Hawes or the mystery of Jimmy Rowles, and Guaraldi probably would only have had a home-town career if it weren’t for an innovative composition that tuned into the early-sixties Zeitgeist.

Disc jockeys picked up on Guaraldi’s “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” even though it was stuck at the back of a minor concept album, Jazz Impressions of Black Orpheus. Until the album’s concluding track, the pianist is merely a light and competent mix of Red Garland and Bill Evans, but “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” feels like the start of an optimistic new era. In short order, the song won a Grammy for Best Original Jazz Composition and was covered by many non-jazz artists. Indeed, most easy-listening instrumental hits since owe a debt to “Cast Your Fate to the Wind.”

When the budding producer Lee Mendelson searched for composer for a project about Charles Schulz and Charlie Brown, Guaraldi, a fellow Bay Area talent, seemed like an obvious choice. Mendelson later said, “I was driving over the Golden Gate Bridge, and I had the jazz station on—KSFO—and it was a show hosted by Al ‘Jazzbo’ Collins. He’d play Vince’s stuff a lot, and right then, he played ‘Cast Your Fate to the Wind.’ It was melodic and open, and came in like a breeze off the bay.”

It’s common for a producer to suggest to a composer, “I like this temp track—give me this but a little different.” Although Mendelson may not have said exactly those words to Guaraldi, there’s no doubt that the pianist went back to “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” when working out “Linus and Lucy.” Many details are imitated exactly. The main argument of “Fate” is a strong, syncopated, even eighth-note melody harmonized in diatonic triads floating over a left-hand bagpipe and bowed bass, followed by an answering call of gospel chords embellished by rumbles in the left hand borrowed from Horace Silver.

This general scheme is followed for “Linus and Lucy,” even down to the same key, A-flat.

What is notably new in “Linus and Lucy” is the syncopated piano left-hand ostinato. (The bass still has that sustained bowed note, which is simply a genius bit of arranging.) Over the ostinato is a very old trick indeed: horn fifths, the same sequence of dyads used by European composers for hundreds of years to suggest hunting in the open air. In classic American fashion, Guaraldi steals that Old Country material and marries it to African-influenced rhythm in the bottom. Boom. You’ve got a hit.

The strong upbeat that begins the ostinato might be somewhat hard to hear correctly, at least for those unaccustomed to a syncopated style. I’ve sat down at the piano at parties and played “Linus and Lucy” at least a hundred times over the years, and somebody always claps along in a way that indicates he or she hears the upbeat as the downbeat. Few, if any, other pop piano works create this kind of rhythmic uncertainty within a significant portion of the intended audience. (It might be added that the delightful way the cartoon characters dance in the original program is completely unsynchronized to the music.)

Both “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” and “Linus and Lucy” also have a short central section of 4/4 swing. Guaraldi’s jazz improvisations on “Linus and Lucy” are blocky and just barely acceptable. It is doubtful that the casual fan waits for those solo sections. The meat is the main tune. While the jazz is going on, you talk to your friend until the theme comes back. (After all these years, I still find the off-key D dominant stuck inside the end of the solo section of “Lucy” a completely unacceptable modulation.)

Guaraldi had trouble surmounting the tremendous success of A Charlie Brown Christmas and the corresponding best-selling soundtrack. His later output lacked the same fresh inspiration, and he didn’t grow as a serious jazz pianist or as a compelling tunesmith. Although the writer Derrick Bang gamely makes a case for depth and breadth in the valuable biography Vince Guaraldi at the Piano, most of us will remember Guaraldi for “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” and a few cartoon cues.

Still, this slender number of magical confluences are far more than most people get. It certainly would be wrong to omit Guaraldi from the jazz history books. The simple but effective techniques that Guaraldi pioneered, especially in “Cast Your Fate to the Wind,” were important to future folksy jazz tunes from Gary Burton, Keith Jarrett, Pat Metheny, and others.

More importantly, A Charlie Brown Christmas remains the ultimate gateway drug. Countless listeners have responded to Guaraldi’s optimistic swinging piano by searching for another hit of that tasty rhythmic realm.

I enjoyed your appreciation of Vince Guaraldi and his contributions to playing and popularizing piano jazz. My dear departed friend Christopher Shea, who as a child was the voice actor of Linus in the Peanuts animated specials, told me that his favorite part of doing the shows was sitting on the piano bench next to Vince, who was apparently present and played live on set during production.

I'm a big Guaraldi fan. He's really good in the 1958 Stan Getz/Cal Tjader record with Billy Higgins, Scott LaFaro, and Eddie Duran, not to mention the late 50s Monterey Jazz fest stuff with Cal Tjader.

And it's not a great recording, but his trio sounds good with Ben Webster.

https://youtu.be/3_X3yxGhgyw?si=PwPAEq7SuLwiHm3J

And the Grace Cathedral concert. And his work with Bola Sete. There are some concert recordings where Guaraldi plays guitar, and those are truly awful.

just my 2 cents