In the best modern jazz, the drummer is loud and busy. It is a basic structural requirement of the music. Probably this intensity relates to the traditional African drum choir, where a thicket of rhythm is produced from a team of community-sourced experts.

John Coltrane was the apex. But Coltrane could have not gotten there without Elvin Jones. Andrew White wrote in his treatise, Trane ‘n Me:

“Trane was structuring his music around Elvin. This was the main source of the symmetry in Trane’s music… Breath is life. The music must breathe. Elvin was the breath in Trane’s music. …It was the manipulation of standard devices that established Coltrane as a thorough improvisor as well as a spontaneous creator, but it was the Elvin Jones grammar that brought these elements into clear focus.” (see footnote 1.)

Elvin Jones ended up not being able to make every gig, so Coltrane needed a sub. What to do? Not every drummer could fill Elvin Jones’s shoes…

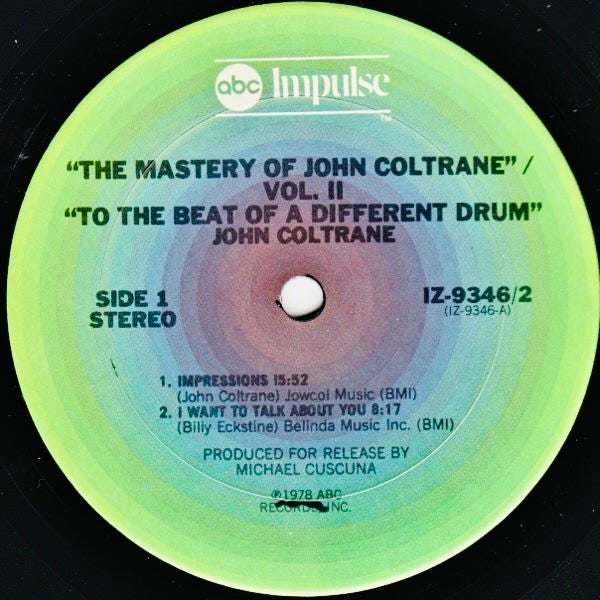

On his 50’s records, Coltrane mostly used Philly Joe Jones and Art Taylor. Philly Joe and A.T. were two of the greatest of all time, but they were also simply not busy and interactive enough for the structure of Coltrane’s 60’s music. Trane tried a few people, but the one who ended up being on official releases was Roy Haynes. (In time, Michael Cuscuna collected the Coltrane/Haynes tracks on the two-fer To the Beat of a Different Drum.)

On paper, this might have seemed like a surprising choice, for Haynes was an old-school swinger who had spent much of the 1950’s supplying tasteful accompaniment for singer Sarah Vaughan; Haynes was also older than Coltrane and the rest of his quartet with McCoy Tyner and Jimmy Garrison.

But — unlike most of his generation — Haynes knew how to play busy enough to make the basic Coltrane grammar work.

Two tracks are among my particular favorites. On April 29, 1963, at Rudy Van Gelder’s, the band plays “Dear Old Stockholm” in C minor (see footnote 2). For his solo, Coltrane rejects the familiar chord changes and mostly blows on B dominant. After getting it going, McCoy lays out and you hear Jimmy Garrison and Roy Haynes clearly. Incredible vibe from the bass and drums. It’s not “latin jazz,” it is swing, but the kind of know-how Garrison and Haynes are showing is intimately related to the Cuban diaspora. It’s definitely B dominant, but Garrison is playing a lot of open A string, putting the music in a cosmic place. Haynes’s snare drum chatters, marches and struts. A grand pulsation. It’s fun to hear Coltrane encourage Garrison to return to C minor, which eventually happens. McCoy then blows on the changes, which is also great, but that feel in the sax solo is really something else.

Then there’s a live session at the Showboat from July 1963 that has never seen authorized release. The whole thing (which can be heard on YouTube) is wonderful, but I have special reverence for “It’s Easy to Remember,” trio with Garrison and Haynes. It is a lo-fi recording and Garrison is barely audible (in sharp contrast to the noisy audience). But Coltrane is astonishing, especially for the way he plays call-and-response counterpoint with himself midway through the track. Goosebumps.

It’s a superb walking ballad tempo. Haynes starts right in there with sticks (not brushes) and helps push Trane to the other side of majesty:

Footnote 1: The 60-page Andrew White treatise Trane ‘n Me is so fun and so good and probably never will be reissued. I have added it to my dropbox of teaching PDFs. If you don’t have the dropbox, just reply to any TT email with a request.

Footnote 2: “Dear Old Stockholm” is an old folksong with a slightly obscure history; the Wikipedia article is helpful. As far as I know, the 1951 Stan Getz version with the excellent pianist Bengt Hallberg in B-flat minor was the first time a jazz musician recorded “Dear Old Stockholm”; I’ve heard that it was Hallberg’s idea. Miles Davis made it a common practice standard through two terrific recordings, the second one with Coltrane on Round Midnight. Davis added an ominous vamp — was this one of the first cases of a pedal point interlude? — and played on the dark-hued changes. It’s not quite modal jazz yet, but definitely headed in that direction.

Brilliant analysis, as always Ethan! Thank you.