The obits by Nate Chinen for The New York Times and Ben Ratliff for NPR are well done.

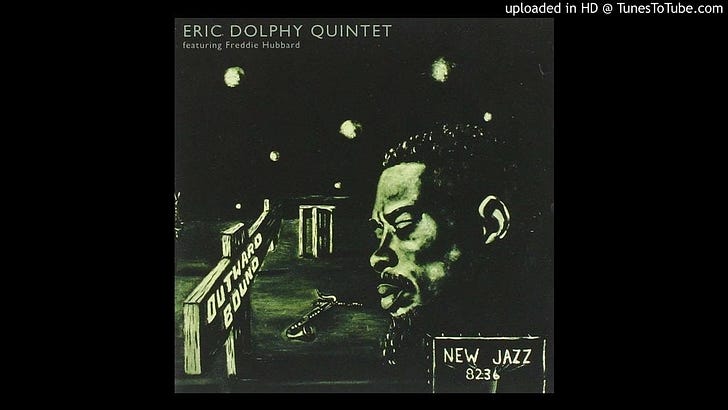

I love the drum intro on “G.W.,” the first track on Eric Dolphy’s first date as a leader, Outward Bound, with Freddie Hubbard, Jaki Byard, and George Tucker.

The famous photo of Bird, Monk, Mingus and Haynes at the Open Door in 1953 was taken by Bob Parent.

Billy Hart has some comments about Haynes in his forthcoming memoir:

Back when I was learning to play in Washington, D.C., there was a real emphasis on finding your own sound. I remember overhearing some elders debate Clifford Jordan: Was Jordan his own man yet, or did he sound too much like Sonny Rollins?

When I heard people talk like that it encouraged me to prioritize individuality. When I finally thought I had “my own style,” I was feeling pretty confident. But then I heard Roy Haynes and realized that he was already doing every possible thing that I thought was “my own style.” I even used to look quite a bit like Haynes, and in the magazines his drum set also seemed like mine.

Eventually, I understood that almost everything comes from someplace else.

Once in a while some young cat will tell me they play “their own music.” That way of looking at it can be out of order unless they are truly advanced. In his 1985 Berklee master class, someone asks Tony Williams, “When did you have your own style?”

Tony responds, “I never did. I don’t feel that way now. I still feel like I’m playing the way that the people that I admire would be playing, if they were me.”

Jack DeJohnette is a good example. He plays like Roy Haynes — he gives it up for his Papa Daddy — but he sounds like himself. If you emulate who you love, your individual body turns it into your own thing. The more music you love, the more music you know, the more you can assimilate and shape your own interpretation of the tradition.

(…)

Roy Haynes could play with anybody and sound like himself. He worked with the original master swinger, Lester Young, as well as the bebop giants Charlie Parker and Bud Powell. Then he held it down for a long run with the diva Sarah Vaughan, but somehow he was just getting started. He went on to make many great records with the new breed of avant-gardists like Andrew Hill and Eric Dolphy, not to mention being Coltrane’s choice as a sub for Elvin Jones. When the music changed in the ’60s from being exclusively song-form oriented to an emphasis on pedal-points and texture, a lot of older drummers were left in the dust. Haynes not only kept up, he set the pace. Chick Corea made all his drummers use the same flat ride that Haynes played on Now He Sings, Now He Sobs.

On top of all that, he can play the slow blues with total commitment. At Dewey Redman’s memorial in St. Peter’s Church, Roy Haynes sat in with Joshua Redman, Pat Metheny, and Charlie Haden and gave us a clinic in just the right texture for a slow blues.

— Billy Hart

My Roy Haynes story: went to see him at a swanky club in NYC in the late 90s. His playing was unbelievably powerful, but there was a table full of loud finance types who were talking throughout the show. While Roy was announcing the band after an amazing, athletic set, one of the loud dudes—trying to make it about himself, like they often do--interrupted him to say "yeah yeah, what's your name?" "My name?" Roy answered slowly and deliberately, staring directly at the dude, "my name is Roy Haynes. I am the last of the bebop drummers. And I was born March 13, nineteen twenty-five. You THINK about that."

I still listen to his 2000’ish albums — Birds of a Feather (a tribute to Charlie Parker) with Roy Hargrove & Kenny Garrett and the Roy Haynes Trio with Danilo Perez and John Pattitucci — fairly frequently. I saw him play at Marcus Garvey Park around 20 years ago. My wife thought the heat and humidity was too much, and Roy, at more than twice our age, was playing drums and sounding great.