The website of Lou Donaldson reads: The Family of Sweet Poppa Lou Donaldson sadly confirms his death on November 9, 2024.

After the big band era and the end of WWII, the serious black musician had a choice. They could play grooving R ‘n B for dancing and drinking, or they could follow the art music path into bebop, where people sat down to listen.

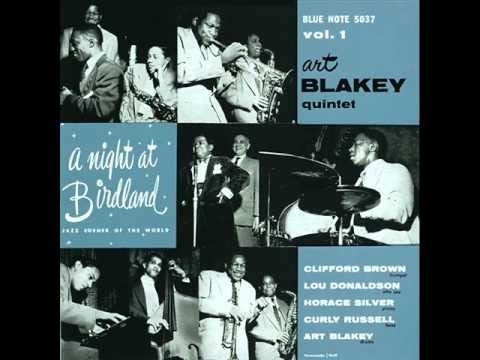

Lou Donaldson gave all this a lot of thought. His thesis at Greensboro College in 1948 was called “The Change from Swing to Bebop.” For a time he took the pure bebop path, and ended up on one of the key documents of modern jazz, the 1954 date A Night at Birdland with Clifford Brown, Horace Silver, Curly Russell, and Art Blakey.

Donaldson died today at 98: It’s strange to think that we are still that close to something as seminal as A Night at Birdland in the timeline. Incredible record. “Split Kick” is a complex and memorable Silver line on “There Will Never Be Another You.” Donaldson solos first, bobbing and weaving like a champion.

Unlike many boppers, Donaldson did not stay tethered to the idea of art music for art’s sake. By the end of the decade he was recording with Jimmy Smith, the man who more or less invented the Hammond organ as an instrument for bluesy party time. It was not quite R ‘n B, for there were no vocals and the horn solos were deep bebop. But the overall package was earthy enough to make the community scene happen.

As rock music ascended in the culture, black musicians fought to keep something in the rhythm more sophisticated than a backbeat. “Alligator Bogaloo” from 1967 was an actual hit and confirmed the direction Donaldson would stay in from then on. The drumming from Idris Muhammad is truly spectacular; the funky band is filled out with Melvin Lastie, Lonnie Smith, and George Benson.

Unlike the long knotty lines of “Split Kick,” Donaldson’s alto solo on “Alligator Bogaloo” is comprised of short, punchy, soulful phrases that land right in the pocket.

When I was much younger I considered the intellectual and virtuosic approach of “Split Kick” to be more complicated and sophisticated than the earthy goodness of “Alligator Bogaloo.”

Now I am not so sure.

I didn’t really know Mr. Donaldson, but anyone who played the Village Vanguard regularly would have to meet him, look him in the eye, and hear what he had to say about your music. He was an old-school referee, tough but fair. I never got much more than a frown (I accepted that judgment) but those closer in to the tradition — especially fellow alto saxophonists — could have some hair-raising interactions where Sweet Poppa Lou would simply demand that there be more blues in the music.

That’s when he’d tell you he taught Horace Silver. “Horace didn’t know a damn thing about the blues when I met him in New York,” Donaldson would growl. (Silver grew up in a white community in Connecticut; Donaldson grew up in North Carolina.) “I had to take him into the practice room and learn him the blues!”

The implication was clear: Those present could also use some time in a room with Lou Donaldson absorbing some basic blues.

One of the things I tell my students comes from Lou Donaldson, although I heard it from Paul Motian. Paul said, “I got to New York too late to hear much of the music when it was really happening. Lou Donaldson told me, ‘The real bebop would scare you to death.’”

(In this context the real bebop means Charlie Parker and Bud Powell, like the 1951 bootleg Birdland session with Fats Navarro and Blakey. By the time Donaldson made his Birdland record with Brown and Blakey three years later, the music had already changed a bit.)

Bebop and the blues; the brain and the heart.

A golden alto saxophone hangs around the neck of Lou Donaldson.

Lovely piece, Ethan. There are two New Orleans musicians on "Alligator Boogaloo": Muhammad and Lastie.

A lovely piece!