Russell Malone was on tour with Ron Carter and Donald Vega in Japan when he passed away at 60. The American jazz community was shocked: everyone loved Russell Malone. He was a truly excellent guitarist, deep in the pocket, very tasteful and soulful. As a person, Russell worked hard to make everybody laugh. We sat together at the club or at tour breakfast a few times, and once he called me out of the blue to talk about something he liked posted on Do the Math.

Sophisticated solo guitar statement on "How Deep is Your Love":

UK drummer Martin France has also suddenly died at 60. Martin was a major virtuoso, an idiosyncratic conceptualist, and another very nice man. I didn't know him well but we played together a bit on gigs with Martin Speake and trio with Conor Chaplin, who took this photo.

France is on a lot of great records; one I particularly admire is Winter Truce (and Homes Blaze) by Django Bates. One of the pieces is a calculus-level math drum feature, “X=Thingys x 3/ MF” — MF stands for Martin France — which concludes with the band ferociously rattling biscuit tins as France seems to levitate out of the studio.

Dan Morgenstern has just passed at 95, which means there is one fewer around that shook the hand of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Art Tatum. I appreciate Nate Chinen’s tribute, “Dan Morgenstern kept the faith.”

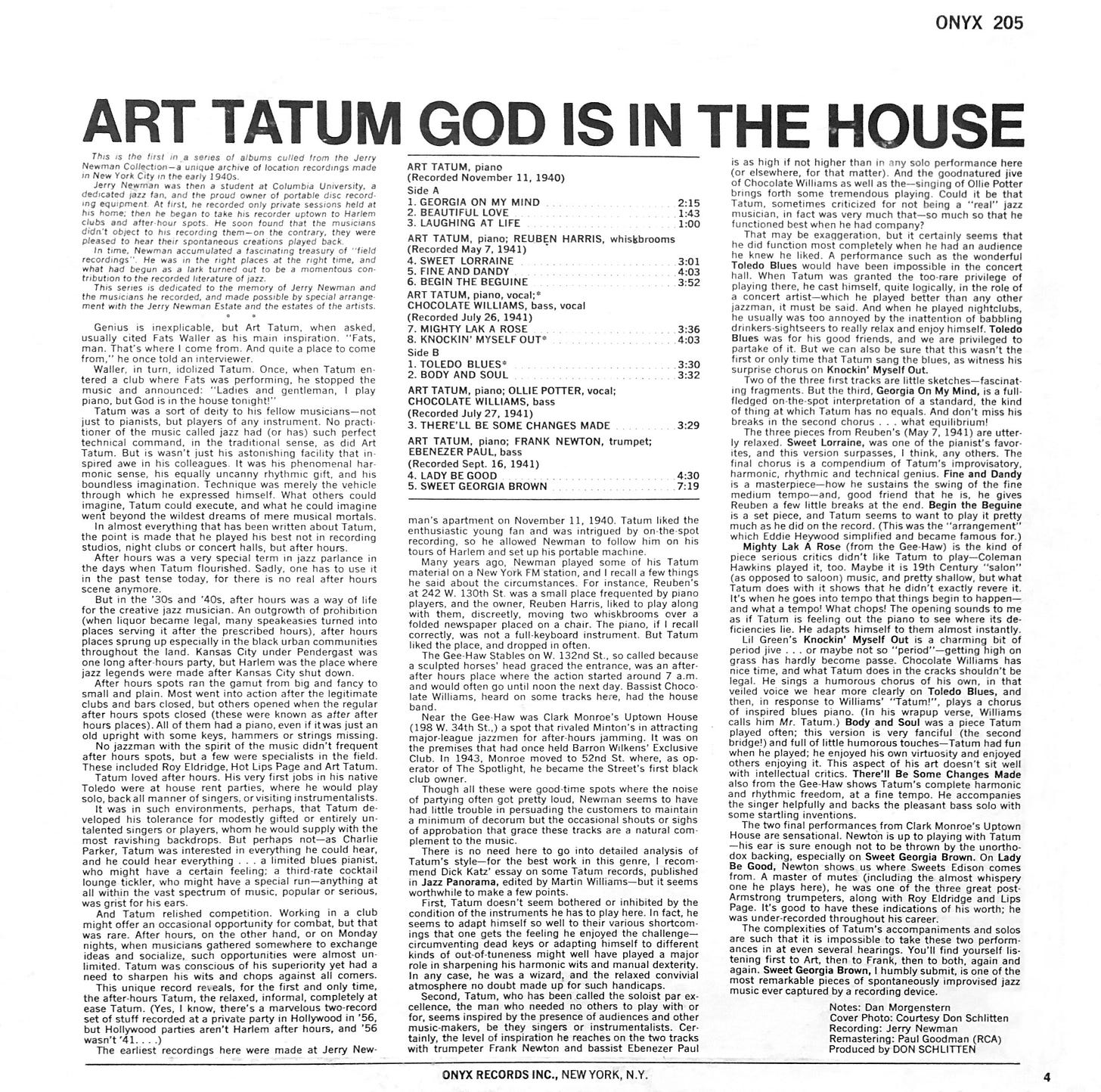

All of Art Tatum is great. There’s literally nobody better, and he never had an off day. (We know this for certain because Tatum was also prolific.) But the 1973 Onyx LP God is in the House is one of a kind, and it made a difference to the history of Tatum reception, partly because of Morgenstern’s liner notes (which won a Grammy).

Those Morgenstern notes include a marvelous evocation of “after hours.”

Genius is inexplicable, but Art Tatum, when asked, usually cited Fats Waller as his main inspiration. “Fats, man. That’s where I come from. And quite a place to come from,” he once told an interviewer.

Waller, in turn idolized Tatum. Once, when Tatum entered a club where Fats was performing, he stopped the music and announced “Ladies and gentleman, I play piano, but God is in the house tonight!”

Tatum was a sort of deity to his fellow musicians—not just to pianists, but players of any instrument. No practitioner of the music called jazz had (or has) such perfect technical command, in the traditional sense, as did Art Tatum. But it wasn't just his astonishing facility that inspired awe in his colleagues. It was his phenomenal harmonic sense, his equally uncanny rhythmic gift, and his boundless imagination. Technique was merely the vehicle through which he expressed himself. What others could imagine, Tatum could execute, and what he could imagine went beyond the wildest dreams of mere musical mortals.

In almost everything that has been written about Tatum, the point is made that he played his best not in recording studios, night clubs or concert halls, but after hours.

After hours was a very special term in jazz parlance in the days when Tatum flourished. Sadly, one has to use it in the past tense today, for there is no real after hours scene anymore. But in the '30s and '40s, after hours was a way of life for the creative jazz musician. An outgrowth of prohibition (when liquor became legal, many speakeasies turned into places serving it after the prescribed hours), after hours places sprung up especially in the black urban communities throughout the land. Kansas City under Pendergast was one long after-hours party, but Harlem was the place where jazz legends were made after Kansas City shut down.

After hours spots ran the gamut from big and fancy to small and plain. Most went into action after the legitimate clubs and bars closed, but others opened when the regular after hours spots closed (these were known as after after hours places). All of them had a piano, even if it was just an old upright with some keys, hammers or strings missing. No jazzman with the spirit of the music didn't frequent after hours spots, but a few were specialists in the field. These included Roy Eldridge, Hot Lips Page and Art Tatum.

Tatum loved after hours. His very first jobs in his native Toledo were at house rent parties, where he would play solo, back all manner of singers, or visiting instrumentalists. It was in such environments, perhaps, that Tatum developed his tolerance for modestly gifted or entirely untalented singers or players, whom he would supply with the most ravishing backdrops. But perhaps not—as Charlie Parker, Tatum was interested in everything he could hear, and he could hear everything ... a limited blues pianist, who might have a certain feeling; a third-rate cocktail lounge tickler, who might have a special run anything at all within the vast spectrum of music, popular or serious, was grist for his ears.

And Tatum relished competition. Working in a club might offer an occasional opportunity for combat, but that was rare. After hours, on the other hand, or on Monday nights, when musicians gathered somewhere to exchange ideas and socialize, such opportunities were almost unlimited. Tatum was conscious of his superiority yet had a need to sharpen his wits and chops against all comers.

This unique record reveals, for the first and only time, the after-hours Tatum, the relaxed, informal, completely at ease Tatum. (Yes, I know, there's a marvelous two-record set of stuff recorded at a private party in Hollywood in '56, but Hollywood parties aren't Harlem after hours, and '56 wasn't '41....)

The earliest recordings here were made at Jerry Newman's apartment on November 11, 1940. Tatum liked the enthusiastic young fan and was intrigued by on-the-spot recording, so he allowed Newman to follow him on his tours of Harlem and set up his portable machine.

Many years ago, Newman played some of his Tatum material on a New York FM station, and I recall a few things he said about the circumstances. For instance, Reuben's at 242 W.130th St. was a small place frequented by piano players, and the owner, Reuben Harris, liked to play along with them, discreetly, moving two whiskbrooms over a folded newspaper placed on a chair. The piano, if I recall correctly, was not a full-keyboard instrument. But Tatum liked the place, and dropped in often.

The Gee-Haw Stables on W. 132nd St., so called because a sculpted horses' head graced the entrance, was an after-after hours place where the action started around 7 a.m. and would often go until noon the next day. Bassist Chocolate Williams, heard on some tracks here, had the house band.

Near the Gee-Haw was Clark Monroe's Uptown House (198 W. 134th St.,) a spot that rivaled Mintons in attracting major league jazzmen for after hours jamming. It was on the premises that had once held Barron Wilkens’ Exclusive Club. In 1943, Monroe moved to 52nd St. where, as operator of The Spotlight, he became the Street's first black club owner.

Though all these were good-time spots where the noise of partying often got pretty loud, Newman seems to have had little trouble in persuading the customers to maintain a minimum of decorum but the occasional shouts or sighs of approbation that grace these tracks are a natural complement to the music.