TT 429: The ‘Uncrowned King’ at 100: Kenny Dorham plays ‘It Could Happen to You’

guest post by Mark Stryker

(For the Dorham centennial, a reprint of an article by Mark Stryker originally published in JazzTimes. Thanks also to the great Michael Weiss for the groovy transcription. — ei)

Here’s a game I like to play that’s a variation on the familiar challenge of choosing favorite records to take to a desert island. I call it “One Artist, One Solo.”

Pick a jazz musician. If you could listen to just one solo by that player for the rest of your life, which would it be and why? Consider improvisations that best embody the sound, style, personality, and individualism of the player. Now think about how those solos make you feel. The one that most fires your emotions should get the nod.

That brings me to Kenny Dorham, born 100 years ago today on August 30, 1924. The Uncrowned King, as Art Blakey once called Dorham, was a beautifully expressive trumpeter but underrated throughout his lifetime. While K.D. (as he is known to his admirers), has earned a measure of wider recognition and critical attention since his untimely death at age 48 in 1972, he remains more celebrated among bebop-savvy musicians and connoisseurs than the general jazz audience.

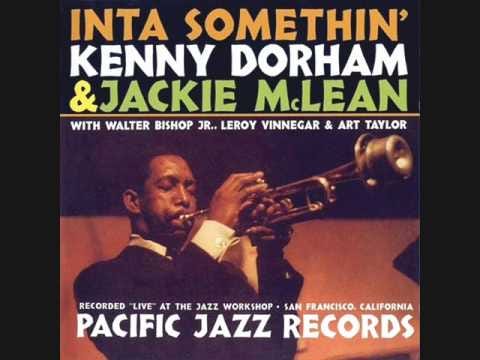

The Dorham solo that slays me most is “It Could Happen to You,” recorded live in 1961 at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco. It appears on Inta Somethin’ (Pacific Jazz), which discographies list under Dorham’s name though he co-leads the quintet with Jackie McLean. Blue Note reissued this gem in its Tone Poet series earlier this summer. K.D.’s ride on “It Could Happen to You” is redolent of everything I love about the trumpeter’s aesthetic, yet it’s also a unique entry in his catalog.

Pianist Michael Weiss graciously provided the accompanying transcription of Dorham’s three choruses.

Dorham does not command attention with Gabriel-like power, brassiness, or bravura technique. As “It Could Happen to You” makes clear, he seduces listeners with the soulful warmth, colorful wit, and understated wisdom of the hippest bon vivant on the scene. Everything about his approach is relaxed, expressive, swinging, personal—his crepuscular sound, lyrical melodic invention, harmonic acuity, piquant dissonances, behind-the-beat time feel, varied tonal shadings, myriad articulations, and sly phrasing that snakes through the chords. K.D. masterfully builds harmonic and rhythmic tension and then resolves them like a magician pulling rabbits out of a hat.

Born in rural east Texas and raised in Austin, Dorham came of age during the first flush of bebop. He worked with the seminal big bands of Billy Eckstine and Dizzy Gillespie before joining Charlie Parker’s Quintet for two years in 1948-50. Gillespie and Miles Davis were important influences, but the elongated running phrases and slick turnbacks Dorham plays with Bird evince an emerging originality.

Dorham’s most fertile period lasted from 1955 to 1964. He worked and recorded with Art Blakey and Max Roach, led his own bands, blossomed as a composer, and recorded regularly as a leader. He also forged a landmark partnership with vanguard tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson documented on five Blue Note LPs in 1963-64. Dorham navigated a convincing path through the stylistic shifts of his time, from bebop to hard bop to postbop, in a way few of his contemporaries matched.

“It Could Happen to You” was written in 1943 by composer Jimmy Van Heusen and lyricist Johnny Burke and introduced as a ballad in the film And the Angels Sing. By the time Dorham recorded it in 1961, it was usually played as a medium swinger. It’s a 32-bar A-B-A-C form, whose attractive melody and uncomplicated but rewarding harmony have made it a jazz standard.

The first things you notice about Dorham’s performance are the dark-complected allure of his tone and the urbane way he makes the melody his own. The flirty bounce, suave phrasing, and sassy smears speak to the heart; K.D. drops a sigh and down you tumble. A pecking, two-bar break finds him gliding into his solo with soft-shoe elegance; pianist Walter Bishop Jr., bassist Leroy Vinnegar, and drummer Art Taylor shift from a two-beat dance into swinging 4/4.

The harmony moves fastest in the first four bars of the A sections, allowing Dorham to thread the changes with sophisticated lines laced with chromaticism. When the harmonic rhythm slows, he returns to Van Heusen’s melody, quoting it directly or paraphrasing it creatively. The recurring melodic and rhythmic rhymes unify the solo thematically and contrast effectively with Dorham’s bustling ideas. All this underscores his gift as a compelling storyteller.

Just how much Dorham leans on the melody is both striking and atypical. Nearly half (!) of the solo’s 96 bars are derived from the melodic contour of the song. Dorham defaults to the melody in the second half of every A section with only one exception. In addition, his first four bars of every B and C section also echo the melody. I don’t know any other Dorham improvisation so saturated by the written tune.

Dorham saunters furthest afield in the second chorus, the most imaginative and thrilling of the three. This is vintage K.D. He opens with a serpentine four-bar phrase that traces an up-down-up journey along diminished tonalities. The eighth notes are played nearly even and deliciously behind the beat, articulated in such a way that they sound slightly detached yet enveloped within a purring legato. How the hell does he do that?

He follows up with startling triplets in bars 7 and 8 while soaring to the highest pitch of the solo, an E-flat (trumpet key). Dorham launches into a turnback in bar 13 and weaves his way back to the tonic via his defining signature move: a tritone-dominant substitution in bar 16: F-sharp7 in place of C7. Bebop!

I savor other details too, like the loose rhythmic slurs in bars 5-7 of the first chorus. Spend time with this solo and you’ll find your own cherished moments. I can’t guarantee that it will become your favorite Dorham solo, but I promise that you will end up falling in love with the man with the horn.

CODA

While “It Could Happen to You” is my favorite Kenny Dorham solo, here are five others that deserve an honorable mention. I could easily add a dozen others.

“Falling in Love with Love,” from Dorham Jazz Contrasts (Riverside, 1957) — Expansive and inventive melodic lines that stretch f-o-r-e-v-e-r in a memorable solo delivered in a nonchalant gait.

“Old Folks,” from Dorham Quiet Kenny (New Jazz, 1959) — An exquisitely melodic reading at a walking tempo with a heartfelt trumpet tone, plus Flanagan, Chambers, and Taylor playing like angels.

“Short Story,” from Joe Henderson In ’n Out (Blue Note, 1964) — An inventive Dorham original begets a potent solo in a postbop idiom with JoeHen, McCoy Tyner, Richard Davis, and Elvin Jones.

“Yardbird Suite,” from Max Roach The Max Roach 4 Play Charlie Parker (Mercury, 1957) — Who needs a zillion choruses? K.D. winks at Bird’s original solo and then says everything that needs saying in one 32-bar pass.

“Solid,” from Sonny Rollins Movin’ Out (Prestige, 1954) — K.D. was a GREAT blues player, soulful and expressive, and dig the 10-bar snake that spans his second chorus.

— MARK STRYKER