TT 423: Give Me a Complex

Matt Mitchell, Miles Okazaki, Anna Webber, Kim Cass, Alec Goldfarb, Phillip Golub, Zekkereya El-Magharbel

The thought leaders keep breaking the sound barrier. “Modern Jazz” doesn’t really describe the idiom, “New Music” was always a bit bland. In the liner notes to Phillip Golub’s Abiding Memory, Vijay Iyer dubs the idiom “New Brooklyn Complexity,” which is pretty good and just might stick. Whatever it is, it’s here to stay, and the results have become pretty darn astonishing.

Most of the records reviewed in this post are from 2024, with the exception of the albums by Anna Webber and Zekkereya El-Magharbel, both from 2023.

Matt Mitchell Zealous Angles

Miles Okazaki Miniature America

Anna Webber Shimmer Wince

Kim Cass Levs

Alec Goldfarb Fire Lapping at the Creek

Phillip Golub Abiding Memory

Zekkereya El-Magharbel 8 Quranic maqamat organized by size

Links to Bandcamp are provided. If you like the sounds, buy the music.

Sincere thanks to these independent record labels for fighting the good fight: Pi, Cygnus, Intakt, Infrequent Seams, Endectomorph. It’s lonely out there and nobody is making a dime.

The pianist who sits dead center at the nexus of jazz, improvised music, and modernist composition is Matt Mitchell, who I first heard playing wonderful piano with Tim Berne about fifteen years ago.

Tim Berne is one of the godfathers of the idiom. In addition to writing copious amounts of mixed-meter atonal pitches at a time when that sort of thing was uncommon, Berne also embraced something of a punk-rock aesthetic. Classic early Berne records from the late ’80s and ‘90s have odd-meter rock drums played by Joey Baron; this kind of drumming soon became an essential element to the idiom. Like Ornette Coleman, Berne has an intuitive and charismatic harmonic system. (At DTM I have interviewed Tim at length about how he found his way.)

His opposite number is Steve Coleman, two years younger, another alto saxophonist, but someone who prioritizes tight parameters in every direction of composition and improvisation; Coleman invented the term “M-base” to describe his ideas and cohort. Compound meters are derived from African sources, and melodic material is often connected to John Coltrane’s use of the pentatonic scale. Classic early Steve Coleman and Five Elements records from the late ’80s and ‘90s had odd-meter drumming from Marvin “Smitty” Smith that was more like funk than rock. Coleman has also worked successfully with traditional jazz musicians. (At DTM I interviewed Steve in collaboration with Charles McPherson on the topic of Charlie Parker.)

Berne’s tight melodies give away to expressionist and theatrical freedom, Coleman’s avant music is always connected to a strict form. They aren’t the only two progenitors of the idiom at hand — when we go to a generation or two older, we automatically include Anthony Braxton and Henry Threadgill, for starters — but Berne and Coleman are impossible to leave out. (It’s also always worth remembering that Tim Berne emulated his mentor Julius Hemphill, while Steve Coleman learned from Bunky Green and Von Freeman in real time.)

While I first heard Matt Mitchell with Tim Berne, earlier this summer Mitchell was playing with Steve Coleman at the Stone.

(cover art by Kate Gentile)

Mitchell’s new recording is Zealous Angles, and the record release gig is this coming Monday, August 12, at the Jazz Gallery, the club with the appropriate slogan, “Where the Future is Present.”

While still complex, Zealous Angles is actually somewhat less complex than many Mitchell projects. Bassist Chris Tordini, drummer Dan Weiss, and Mitchell himself all get the same single piece of paper, comprised of lines that should happen at the same time.

From the press release: “The compositions on Zealous Angles reflect Mitchell’s recent interest in multiple asynchronous cycles using polyrhythm and polymeter. The pieces contain anywhere from two to six lines of different lengths, with the performers having the freedom to play any of the lines and also interpret and improvise within and among the material.”

Tordini and Weiss are major virtuosos on top of their game, and they enable the polyrhythm and polymeter concept to go down smoothly. Indeed, at first blush, Zealous Angles sounds like a “normal” jazz piano trio dealing with scraps of cues in the studio. Herbie Hancock’s sparse yet scientific Inventions and Dimensions seems relevant, and when I suggested that album to Matt, he replied, “That is a totally apropos comparison. Also sometimes that’s my favorite Herbie album.”

The catch is that Mitchell and Tordini have to extend tonality. The pitches hover in the air, a whirl of chromaticism keeping them from falling to an obvious tonic.

To hear more extensively organized Mitchell music, I recommend 2017’s A Pouting Grimace, especially “plate shapes.” The score is formidable on the page, a relentless sequence of irrational ostinati. Some of the lines are nearly twelve-tone, while drummer Kate Gentile dishes out the big beat. The Second Viennese School meets Heavy Metal!

The absurd bassoon solo by Sara Schoenbeck is nothing but pure delight. Other musicians on this stellar track include Jon Irabagon (saxophone), Kim Cass (bass), Ches Smith (vibraphone), and Patricia Brennan (marimba).

[A Pouting Grimace on Bandcamp]

(cover art is “Miniature America” by Ed Ruscha (1982))

Miles Okazaki and Matt Mitchell are frequent collaborators; they are also both 49 years old. Okazaki played with Steve Coleman for several years, and when I heard some of Okazaki’s earlier albums I thought they were an extension of the M-Base tradition, enlivened by something atmospheric (thanks to the guitar) and something Monk (Okazaki is an expert in Thelonious, and has recorded the complete Monk canon arranged for solo guitar).

The new Miniature America is different, and could be a breakthrough. While meticulously assembled, it is absolutely a blast to listen to, informed by a generous — even carefree — spirit.

Okazaki brought friends and collaborators into the studio (Patricia Brennan, Matt Mitchell, Caroline Davis, Anna Webber, Jon Irabagon, Jacob Garchik, Ganavya Doraiswamy, Jen Shyu, Fay Victor), developed some precisely-controlled material, sent everybody home, worked out some appropriate after-the-fact guitar parts, and went to town during post-production.

The attractive opening piano piece “The Cocktail Party” is accompanied by spoken word from all hands. This piano music sounds relatively normal, but there’s there’s a wicked counterline and 9:7 polyrhythm. (It’s a good thing Matt Mitchell was available.)

There’s a hilarious scrolling score video for “Lookout Below” that strings together fragments from the party members:

Another highlight is “The Cavern,” with trombonist Jacob Garchik playing against a “simple” progression on the guitar. Simple it may be, but the progression also keeps going down in quarter tones. (?!)

The whole album is that kind of “simple.” One way to humanize complexity is through song, and the vocal features for Ganavya Doraiswamy, Jen Shyu, and Fay Victor are memorable.

References abound in Okazaki’s copious notes. Ed Ruscha, Immanuel Kant, Ken Price sculptures, Sol Lewitt wall drawings, dozens of poets….producer David Breskin also clearly played an important role in this major project. It’s all explained in the 36-page booklet, not that reading the booklet is a requisite to enjoying the sounds.

[Miniature America on Bandcamp.]

(cover art and graphic design by Jonas Schoder, photo by Alice Plati)

Microtonality was always part of jazz, traditionally we call it “the blues.”

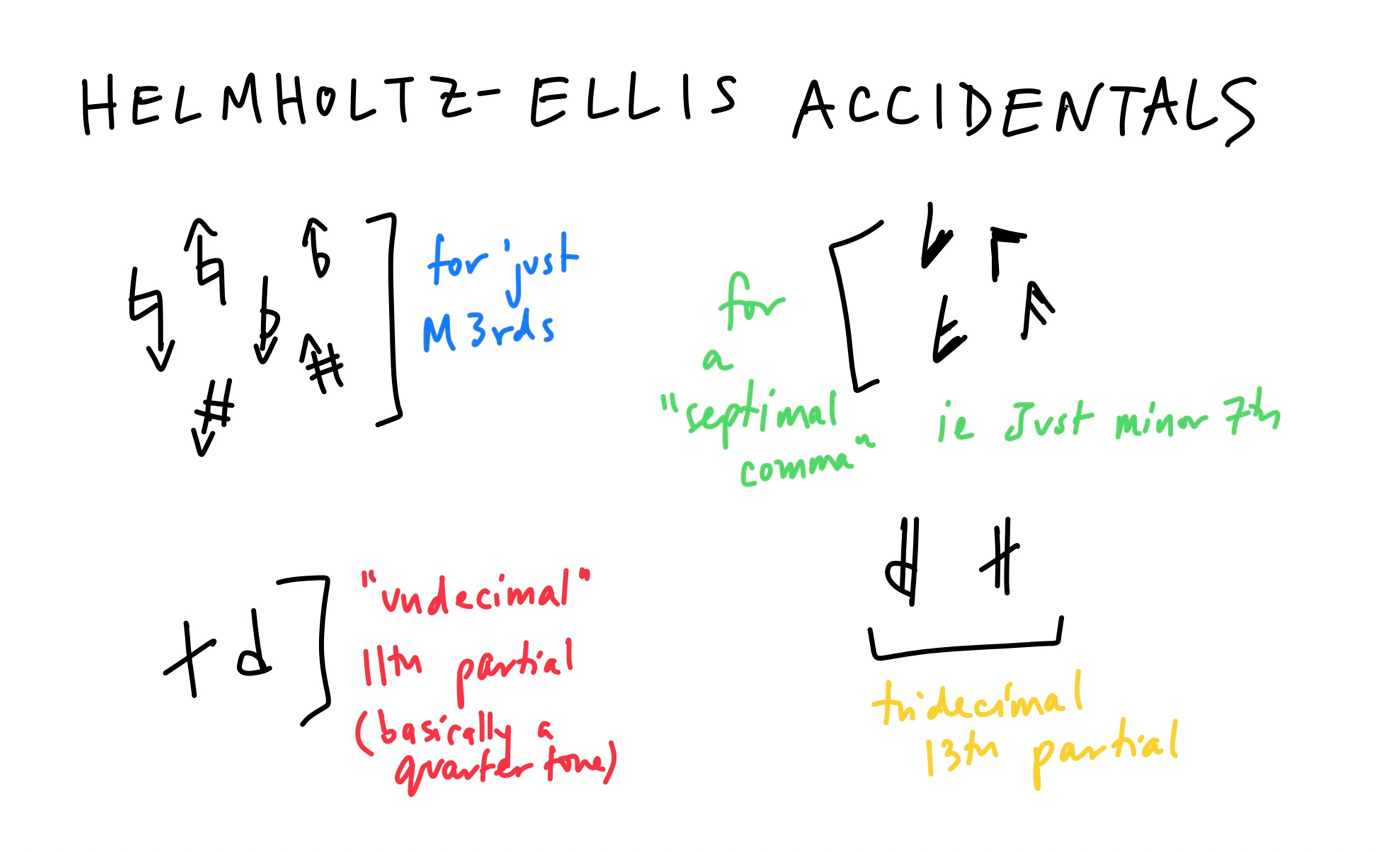

Okazaki’s tunings on “The Cavern” just above are parallel and relatively obvious. For her new release Shimmer Wince, Anna Webber dives straight into something a bit more complicated. A page on her website gives a lot of detail.

i am using a simplified helmholtz-ellis accidental system. simplified because for my purposes, legibility was more important to me than enharmonic accuracy. for me, it’s easier to read B quarter flat as opposed to A three-quarters sharp. in the same way, it’s easier to read a single lowered septimal comma rather than a raised double septimal comma. i occasionally used an accidental with an arrow for 5-limit harmony, but in some cases i omitted it as i felt that those of us with flexible pitch will actually tune our major thirds correctly by ear. i rounded undecimals and tridecimals to the nearest quarter-tone for the purposes of ease of notation. often, especially in my part, i wrote a ratio above the pitch, so that tuning would be easier.

Anna joked to me that this was “inside baseball,” and it’s true, this kind of math is only required for her associates on the record, a quintet comprised of Adam O’Farrill (trumpet), Mariel Roberts (cello), Elias Stemeseder (synthesizer), Lesley Mok (drums), alongside the leader on tenor sax, flute, and bass flute.

Replacing bass with cello automatically conjures the lineage that goes back through Tim Berne with Hank Roberts to “Dogon A.D.” with Julius Hemphill and Abdul Wadud. From that angle, Webber’s “Periodicity no. 1” (with funky pizzicato cello from Mariel Roberts) could almost be called, “In the Tradition.” Lesley Mok is a major asset, playing the groove with a fat bass drum tone and a certain relaxed sway.

“Wince” is a standout composition: the haunting melody halfway through is genuinely thrilling, an effect created in part by the microtones. (The track begins with a trumpet solo; pages 3 and 4 of the score have the lyric theme and some of its development, which occurs just before the two-minute mark.)

While the microtonality already sounds effortless, we are still at the beginning of this tuning journey. Who knows where this level of harmonic control will lead us?

Part of the reason to do any system is esoteric or even spiritual. Going deep into the math promotes connections that couldn’t be found any other way. Someone like Anna Webber is out there, alone, interrogating the new. The math is restrictive, but it is also full of endless possibility.

The Anna Webber/Angela Morris big band performs at the Jazz Gallery on August 14.

(cover art by Dan Hays)

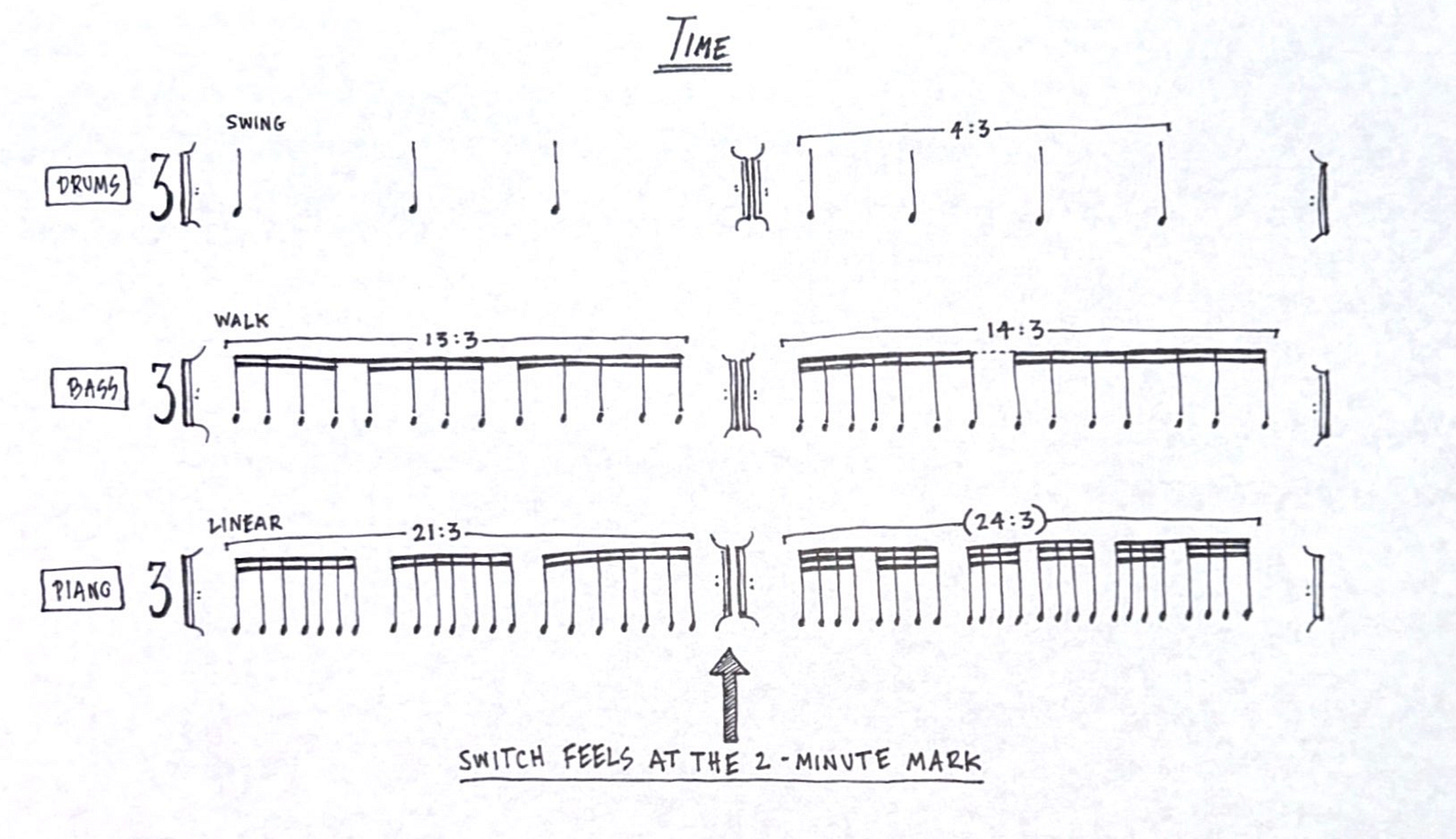

Both Anna Webber and Kim Cass turn up on the Matt Mitchell album A Pouting Grimace; both are also 39 years old. If Webber is dealing with the most advanced mathematical tuning, then Cass is dealing with the most advanced mathematical rhythm.

His new recording is Levs, mainly a trio with Matt Mitchell and Tyshawn Sorey, although there is a certain amount of thickening from synthesizer, Laura Cocks (flutes) and Adam Dotson (euphonium).

(…it’s easy…just walk a fast even 13 in the time of 3…you got that, right?…)

It’s safe to say there’s never been a bassist like Cass, who rules the roost in the manner of Jaco Pastorius (except on an acoustic instrument and in a modernist context).

From the press release: “The compositions on Levs were inspired by the images of a selection of Cass’s favorite hand-notated classical scores, including those of 20th century figures like Karlheinz Stockhausen, Arnold Schoenberg, and Pierre Boulez. They inspired for him a different way of looking at music, illuminating a connection between the written form and the composers’ musical personalities. Cass is also a habitual doodler, and drawing is also an important aspect of his artistic expression. He writes out his scores meticulously by hand, paying as much attention to the aesthetics of the notation – viewing them as works of visual art – with the shape of the images and music naturally informing each other.”

It’s fairly common for those working in this idiom to name-drop Karlheinz Stockhausen, Arnold Schoenberg, and Pierre Boulez. What sets Levs apart is something of 1970’s bad boy fusion, as if Weather Report or Mahavishnu Orchestra understood Schoenberg, Boulez, and Stockhausen. There’s even an atmospheric vamp ballad, “Ripley,” the sort of respite found on many WR or MO records.

The opener is “Slag.”

The trio sounds great. It is more than cool that the Pulitzer-winning Sorey — now poised to be the musician of an era — still makes time in his schedule to rehearse and record such demanding and under-the-radar music.

However, some of the best things on Levs feature Cass front and center. This bass playing is just too much.

Mitchell and Okazaki are almost 50, Webber and Cass are almost 40. To finish up, a quick look at three albums from exciting emerging composers around 30. While within the idiom, these releases also showcase explicit engagement with diverse traditional forms.

Alec Goldfarb Fire Lapping at the Creek

Goldfarb, guitar

David Leon, alto sax

Xavier Del Castillo, tenor sax

Zekkereya El-Magharbel, trombone

Chris Tordini, bass

Steven Crammer, drums

As proclaimed above, we always had microtonality in jazz, and we call it the blues. Alec Goldfarb has seized on the blues aesthetic and has reverse-engineered a kind of old-school rawness through written microtonality and polyrhythm. It’s a brilliant gambit.

Are you ready for this?

(This score excerpt of “Fire Lapping at the Creek” starts a bit before four minutes in, after the tenor solo. The intonation is carefully notated, the drums have quintuplets, and so forth.)

This whole album is a bright dose of unreality. While these horn players are all new names to me, they all sound great. Chris Tordini holds it down, a man born to this microtonal mission, and gets a terrific short dark descending arco bass feature on “I Know My Name Is Written in the Kingdom.”

The press kit explains further:

The Blues itself possesses many secret things, and in these compositions Alec Goldfarb brings out this transcendent quality by making secretive the known- ghostly tunings spiderweb out from blue notes, irrational rhythms overtake loping shuffles. The improvisers in this all-star sextet contribute equally to this resynthesis of the Blues from its basic components, completing the magic trick that we have been transported somewhere alien, some distant shore, but somewhere familiar.

[Fire Lapping at the Creek at Bandcamp]

Phillip Golub Abiding Memory

Golub, piano

Alec Goldfarb, guitar

Daniel Hass, cello

Sam Minaie, bass

Vicente Atria, drums

The liner notes are by Vijay Iyer; I suspect Golub also admires other leading pianists connected to the idiom such as Matt Mitchell, Craig Taborn, David Virelles, and Kris Davis. However, Golub isn’t really that kind of extroverted and spiky new music pianist. Golub is a romantic, with a lush tone. The first paragraph of the opening “Catching a Thread” is a marvelous sentimental utterance, Eubie Blake meets Ran Blake:

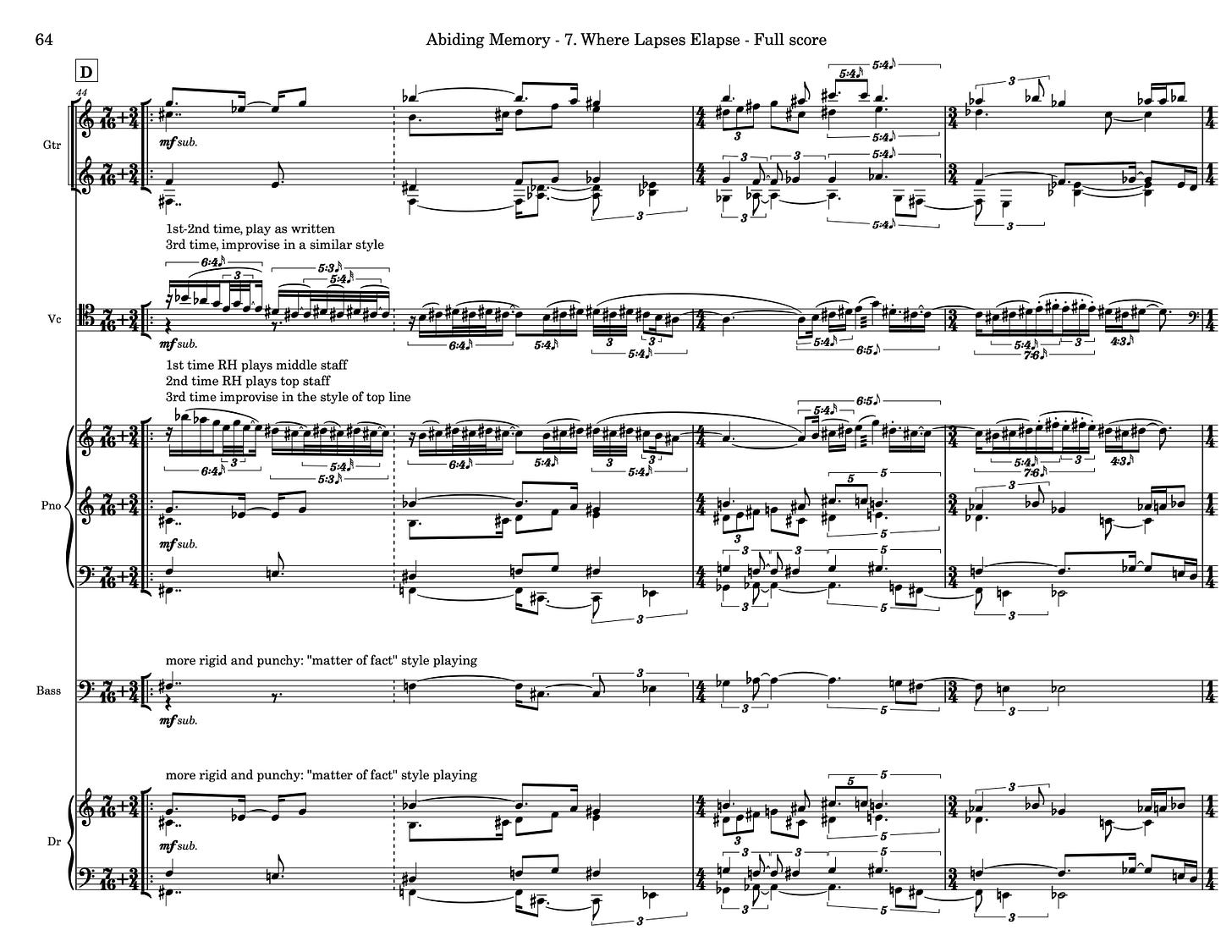

The whole of Abiding Memory is almost entirely written out. There are improvised elaborations here and there, but when I looked over the complete score (which can be purchased) I was amazed at the level of notated detail. Indeed, my jaw was on the floor during “Where Lapses Elapse,” which ends up being a kind of baroque trill study gone horribly wrong (I mean hilariously right).

Guitar, cello, piano, bass, drums. It’s an unusual quintet, and while every member gets an attractive cadenza or two, the main argument is rich instrumentation and rich counterpoint. In the press release, Golub cites Brahms and Scriabin. As with the old school blues from Goldfarb, it seems provocative and fresh to feed some of that kind of traditional harmonic control into the idiom.

Quite a bit of Abiding Memory could be played without drums in a chamber music concert by classical musicians. But! It is the drums that makes the difference. At the top of this page, when discussing Tim Berne and Steve Coleman, I name-checked Joey Baron and Marvin “Smitty” Smith.

For Phillip Golub, it is Vicente Atria. For Alec Goldfarb, it is Steven Crammer. Kim Cass has Tyshawn Sorey, Anna Webber has Lesley Mok. The cited Matt Mitchell tracks feature Dan Weiss or Kate Gentile. On every tune, each drummer has to make a thousand small but crucial decisions while seeking to project the music adequately.

I looked up Zekkereya El-Magharbel’s page after enjoying the trombone playing on the Goldfarb blues record. 8 Quranic maqamat organized by size is utterly gorgeous.

Gustav Mahler called the trombone “The voice of God.” In their notes El-Magharbel states, “Many proofs on Islamic Jurisprudence have been written regarding whether or not music should be forbidden on account of its incredible effect.”

These are original improvisations on the traditional modes; the unaccompanied recital concludes with “Pyramids,” which is less traditional and has a bit more reverb than the previous seven pieces. The work resonates; the future awaits.

[8 Quranic maqamat organized by size on Bandcamp]

[MaqamWorld is an online resource dedicated to teaching the Arabic Maqam modal system]

This loose group is the most exciting thing going on in creative music today in my opinion. (Kate Gentile's Find Letter X was my favorite album of 2023.) Thank you for bringing more attention to it, and to the names I didn't know yet! And I always love those score excerpts. It's amazing how different music can sound when you know how the musicians were thinking about it while playing.

Adding a late comment just to say thanks for this! I feel like it's good enough if you were to say "These are the cats, check them out" but the extra steps of appreciation + explanation... this was very exciting to read. Now gonna dive in & support these artists