TT 401: Leonard Rosenman, Professional Composer

and his truly obscure but truly excellent piece, Chamber Music V

Almost everyone has probably heard at least a little bit of Leonard Rosenman’s music, for his extensive film credits include East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause, Fantastic Voyage, Barry Lyndon, Bound for Glory, The Lord of the Rings (1978 animated version), Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, and RoboCop 2.

Not too many classic Hollywood composers got a chance to consistently create on their own terms, and Rosenman would end up handling all sorts of styles when employed by the studios. However, Rosenman was a product and a devotee of midcentury atonal modernism, and modernism was how he made his mark in three scores from 1955. The music to East of Eden was “Americana” cut with modernism while Rebel Without a Cause was “jazzy” cut with modernism — but even more shocking was The Cobweb, the first Hollywood movie with a 12-tone score somewhat in the manner of Arnold Schoenberg.

Both John Adams and John Corigliano praised Rosenman, and I suspect that these two important and popular American concert composers saw in Rosenman something of a shared spirit: All three can be admired not just for their music but for simply managing to place something comparatively esoteric in front of general audiences.

Adams went as far as to program and record suites of East of Eden and Rebel Without a Cause, which together he thought comprised Rosenman’s best work. In the liner notes to the Nonesuch recording, Adams helpfully situates Rosenman in the timeline:

Leonard Rosenman is an important transitional figure in the history of film music: a highly skilled composer whose best work evolved during a critical period between that of old school Europeans like Max Steiner and Dimitri Tiomkin and that of the later, more pop-oriented composers of the 60s, 70s and beyond. Rosenman was doubtless one of the most thoroughly schooled musicans ever to work in Hollywood. Before making an acquaintance of director Elia Kazan in New York in 1954, he studied composition and theory at the University of California, Berkeley with Roger Sessions, the most serious of all serious composers. He was thoroughly familiar with all the latest modern techniques in the works of Stravinsky, Bartók and Schoenberg. Most importantly, he possessed one thing Sessions lacked: the common touch, an ability to mirror the American vernacular experience in his music. This was an essential ability for anyone hoping to make a successful foray into commercial film music.

Despite his prodigious output in the world of work-for-hire, Rosenman did not give up on writing “serious” music for the concert hall. Recently I stumbled across a fascinating article in The New York Times from 1982 by Joan Peyser, “Composer Seeks Artistic Prestige After Hollywood.” Peyser dives right in, with a first sentence that is unusually frank: “Leonard Rosenman is a man who is confronting one of the questions of the age: art versus money.”

It turns out that Rosenman had a lot of trouble getting performances of his “serious” music. 40 or 50 years ago everything was much more stratified, people were classified as belonging to one milieu or another and that was that. A lot has changed since then. Surely it would be relatively easy today to find chamber music groups interested in playing modernist sounds from someone who scored Star Trek and RoboCop movies.

According to the Peyser article, the angel who enabled Rosenman to have a few fringe new music gigs in New York was the uncompromising gatekeeper Charles Wuorinen, who programmed Chamber Music II. Peyser also notes the upcoming premiere of Chamber Music V. Both Chamber Music pieces would end up being among the few Rosenman concert scores to be recorded for commercial release.

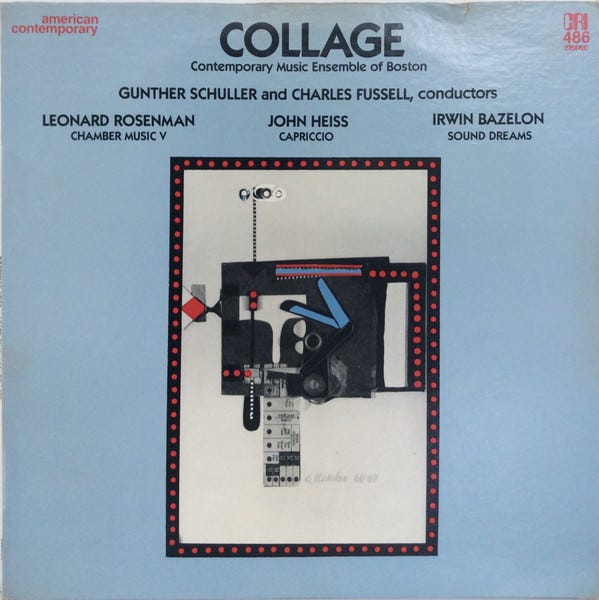

Chamber Music V appears on a low-budget CRI album from 1983 by Collage, the Contemporary Music Ensemble of Boston. (This group evolved into Collage New Music and they are still a going concern.)

The aesthetic of hardcore modernism is an essential component for well-rounded 21-century artistry. It is one aspect of the sublime. Every once in a while I take some piece of hardcore modernism and listen to it repeatedly. This is good for my ears, good for my soul, good for my everything.

Chamber Music V struck me right away as having unusual qualities, so I’ve kept it in rotation for the past few months. This piece is not streaming, which I believe is just an oversight, as many other things from the CRI archives are on the platforms. Though technically illegal, I doubt anyone will object to this upload:

The work lasts 21 minutes and is scored for piano obbligato, flute, B-flat clarinet, two percussionists, violin, and cello. The performers on the recording are new music all-stars, it’s wonderful playing, although I might be able to hear an occasional edit or tape wobble.

Christopher Oldfather, piano — who deserves a special bravo!

Randolph Bowman, flute

Robert Annis, clarinet

Frank Epstein and Thomas Gauger, percussion

Joel Smirnoff, violin

Martha Babcock, cello

Charles Fussell, conductor

Doubters would insist that there is already simply too much hardcore modernism that inhabits the same sound world as Chamber Music V. But I dunno, there’s something about this piece that just catches my fancy. The harmonies and melodies “speak.” Perhaps it is also just a shade theatrical, as if all that Hollywood work-for-hire found its way into how Rosenman shapes an atonal and disjunct narrative. The piano is obviously the jittery protagonist, while the winds and strings wail alongside in uncomfortable microtones. At one point the percussionists swarm the piece like Godzilla, destroying everything in sight. Eventually proud stationary gongs are summoned. For the end, an abrupt piano descent collapses the piece into a puff of smoke.

The work also feels bigger than a septet. This is called “good orchestration,” a slight-of-hand trick that must also be connected to Rosenman’s experience as a practical musician.

I’d like to see the score sometime.

Bonus tracks: In 1977, two years before Chamber Music V, Leonard Rosenman puts “Dies Irae” through a few paces for the “it’s so bad it’s good” cult classic The Car.

Marcus Welby, MD was one of the few television shows that Rosenman worked on that was also a bonafide hit. While the opening symphonic fanfare is typical Rosenman, the big tune over a disco rhythm section lives next to someone like Henry Mancini.

A thread at Film Score Monthly discusses the slender non-film Rosenman discography. Duo for Violin and Piano is streaming, it’s quite attractive if this is your sort of thing. Great performance from Robert Gross and Richard Grayson, and the production values are higher than on Chamber Music V.

Again, just to be clear: The hit theme to Marcus Welby M.D. and the utterly dense and esoteric Duo for Violin and Piano were written at exactly the same time by the same person.

Further reading (thanks to Matthew Guerrieri and Jon Opstad for help with this section):

Film Music: A Neglected Art by Roy M. Pendergast has several pages of manuscript sheets from The Cobweb, and Rosenman is quoted as saying that he basically based the score on Schoenberg’s Piano Concerto.

The Composer in Hollywood by Christopher Palmer goes through the complex cues of both East of Eden and Rebel Without a Cause almost scene by scene.

Double Lives: Film Composers in the Concert Hall edited by James Wierzbicki includes a valuable chapter on Rosenman by Reba A. Wissner. The other composers considered in the book include such celebrated 20th-century names as Bernard Herrman and Ennio Morricone. Few had an easy time getting established as concert composers outside of their film work.

Knowing the Score: Notes on Film Music by Irwin Bazelon is fun but also a bit cranky. Bazelon — another modernist composer represented on the above Collage album — asks leading questions seemingly designed to bring out the grumpy side of those interviewed for this book. Rosenman is no different, who vents at length.

Bazelon: In all the years that you have been writing music for television and films, what percentage of directors and producers that you have worked for knew anything at all about music or how to communicate with you on an elementary level?

Rosenman: I would say less than one percent.

Film Score: The View From the Podium by Tony Thomas includes not just a substantial overview of Rosenman’s work but the article “Leonard Rosenman on Film Music.”

At one point Rosenman praises David Raksin’s “Laura” and complains about Maurice Jarre’s “Lara’s Theme.”

The film Laura was a slightly better-than-average suspense melodrama, based on a contrived and absurd premise. Its musical theme, a haunting ballad by David Raksin, was totally responsible for the film’s becoming something of a “classic.”

[…]

An example of another sort is the score to the recent success Dr. Zhivago by Maurice Jarre. “Lara’s Theme,” which is the central selling point of the score, is plugged and re-plugged by an orchestra seemingly in the last stages of elephantitis. Even the most superficial scrutiny of “Lara’s Theme” disclosed its imperfections (a charitable term). Its amateurishly twisted progressions aiming at modulation (and missing the mark), its actual wrong notes and unlettered harmonic choices simply make a bad tune. But all these elements, repeated incessantly by a huge and bloated instrumentation, succeeded in successfully selling the product and itself to a brainwashed consumer public.

Ouch! Well, I admit I’ve never liked “Lara’s Theme” that much myself, and, yeah, that early modulation from G to B-flat is indeed pretty questionable. In this case I have to side with Rosenman…

[UPDATE, a day later, a few more Rosenman items came in, including a hilarious comment from Tom Myron.]

I am listening Chamber Music V as I write this. I have long felt that avante garde classical music and free jazz converge at some point and this piece supports my notion. Thank for your wide ranging interests! You are certainly making me aware of many artists I would not have encountered. It is great you straddle the jazz and classical words with such an open mind.

Heavy stuff... interesting criticism of Jarre there-- in that case feel it's worth mentioning Jarre's '70s and '80s scores usually seem to be very good (even the synth heavy ones). Most recently, the cue for the closing credits of 'Once apon a Time in Hollywood' is a well- curated and poignant example soundtrack recycling.