(This reprint of a DTM interview, conducted in an East Village restaurant in 2009, is the second of three TT posts about the late great Tootie Heath.)

Albert Heath: I always felt that this music was a tradition that was handed down by my family. My father was a clarinetist, a weekend clarinetist. During the week he was an auto mechanic. But he loved music, especially John Philip Sousa, and he was in the marching band. My mother marched in the band too, in the women’s section. She didn’t play an instrument but sang in the church choir at the 19th Street Baptist Church in Philadelphia.

Together, they always provided us with plenty of music in the house, especially on recording. Duke Ellington, Jimmy Lunceford, Louis Armstrong, Mahalia Jackson: I heard those people from the very beginning. Mahalia was my mom’s favorite.

And when I really got to thinking about playing an instrument, I paid attention to my older brothers, who were listening to Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Ben Webster, Don Byas…people like that.

For drummers I listened to Max Roach, Art Blakey, Kenny Clarke, and Specs Wright, a local drummer who was an amazing musician. He was in my brother Jimmy’s band, and he took me on as a student. I learned most of the rudimental drum studies through him. I kind of cast those aside for a while: you need to be really mature and secure in your musicianship to be able to sit down and deal with the basics. When you’re young you think the basics aren’t hip. So the rudiments I got in early life, I chucked them out, but in later life I’m discovering how important they are, and how much the guys I admired and wanted to be like knew their rudiments. Kenny Clarke was probably one of the most rudimental players in jazz. And Max Roach of course, same thing. His solos were very melodic but you could still relate them to rudiments.

Actually the best young drummers have amazing rudimental control.

But when I was young, I followed my ear and heart. There’s a kind of divine intervention that helps. Alan Dawson always said that it was 90% rudiments and 10% divine intervention! That was his philosophy, and it makes a lot of sense. That divine intervention is what I always relied on, and how I was able to create a unique conglomerate of everything, rudiments included. Whenever I sit down to play, I’m quiet for a couple of seconds. Then I ask permission from the ancestors to allow me to do these things that have already been done.

A joke about that comes from “Sweets” Edison. After I played a drum solo, he said to me, “Yeah, you thought that shit was something, huh?”

I said, “Well…”

“That shit was nothin’ but a bunch of old Sid Catlett licks!” Of course, nobody in the club even knew who Sid Catlett was.

Ethan Iverson: Did you get to see Catlett play?

AH: No, never. But I heard the records.

EI: Who did you get to see live in Philly growing up?

AH: Well, Philly Joe Jones before he moved to New York. Ronald Tucker, who’s on one album with Jackie McLean, the one with the first recording of “Little Melonae.” He was really my hero, because Ronald never practiced but could play anything. Just anything. He’d see you trying something, and he would say, “What’s that you are trying to play? You mean this?” And he could do it. He could hear and play anything, Max Roach solos, you name it. We called him “The Flame,” since he used the hair straightener called Conkaline and let it get red. Conkaline was almost like lye, it would basically burn your hair, and if you weren’t careful, you would end up with red hair, which is what happened to Ronald.

Specs Wright was very technical, a great reader, wonderful smooth hands, clean, the “4”s were exact – but this guy Ronald could try anything and come out of it like magic. I also used to see a wonderful drummer named Charlie Rice around Philadelphia – in fact Rice is still there – and I’m sure I’m leaving some other people out.

Then from New York City guys would come through. Max Roach, Art Blakey, Kenny Clarke – I saw Kenny Clarke with the Modern Jazz Quartet a few times in the beginning.

EI: I like those records of the MJQ with Kenny Clarke.

AH: I do too! I like most of the recordings I heard of Kenny Clarke.

EI: Not just with the MJQ: Your brother and Kenny Clarke is one of the all-time great rhythm sections of the 50’s.

AH: Oh man! Those were amazing records, with Miles and so forth.

One time the Heath Brothers went to Paris. We went to the New Morning where Kenny Clarke was sitting up there playing with a bunch of young kids in kind of a strange environment. He had his eyes closed and it looked like he was bored out of his mind. So Percy waved to the bass player, who recognized Percy and gestured for Percy to come up. He kept playing until Percy was able to take the bass and fall right in. All of a sudden, Kenny Clarke felt this shift in intensity in sound and beat and he opened his eyes. Oh, man! The music just lit up. After the song they embraced. It was great seeing that. We all had such a good time after the gig. He died not too much later on.

EI: What was that beat your brother and Klook play on the Miles album Bags’ Groove?

AH: It was Kenny Clarke’s cymbal beat, and how sparingly he played: he could always find the cracks in the music. When he did something, it was always a lift. Some drummers get carried away and stop listening, maybe because we are doing four or five things at the same time. You want to see if things will work or not, but you’re not really paying enough attention. Drummers have a big responsibility to be happy. We think we need to make everything happen, but it’s not true: everything is already happening, all you need to do is find your place. Kenny Clarke was a master of that. He had a ride cymbal beat…I haven’t figured it out yet. When I hear it today I still say, “Damn, man! Is it a triplet feel or a sixteenth note feel?” It is so distinct. When you listen back it is so different than other drummers. Max and Art Blakey had completely different cymbal beats.

That was the identity during that time. The influence of Tony Williams and Elvin Jones has shifted the emphasis away from the ride cymbal to the orchestration of the drum kit. It’s a bigger sound instead of the light swing with a few accents. Guys now can do some pretty amazing stuff. Drummers are off the page! They can do incredible stuff. We all need to keep listening, though.

EI: What about feathering the bass drum?

AH: That’s an old tradition.

EI: You feather, right?

AH: I try, yeah. A lot of times I get carried away and I stop feathering, and I feel it right away. I know it’s an emptiness if it’s not there. But guys can play without that and still use it as part of the overall sound, and you don’t miss it.

But there’s something about feathering: once you start doing it, everyone on the bandstand – in fact, everyone in the whole place – can feel it. It’s right with the bass, and when you can put it in the right place with the bass, it enhances the bass. If it is too loud, it will make the bassist’s notes sound very short. But if you can do it just right, like the word itself, “feathering,” it works out. Tapping it lightly is the trick to that. I was watching Eddie Locke. He’s got it. And Jackie Williams? He’s another one of those guys that can tap that bass drum…forever! Right through everything, hits and all – you keep thinking, “He’s going to miss it, he’s too busy,” but these guys keep it going.

But they are from the old tradition. The Jo Jones tradition.

Buddy Rich used to play it, but he played it like a truck. Sure, it was right there: it was accurate. But no finesse! You know, I saw Jo Jones sub for Buddy Rich once in Buddy’s big band. When Jo came in, the first thing he did was ask the whole trumpet section to put mutes in. Then he played the whole gig on brushes!

EI: I heard Blakey play the four beats on the bass drum pretty loud, too.

AH: He could do it kind of loud, sometimes. But he used to have a special sheepskin beater on his bass drum that was very soft, and he tuned the bass drum in a special way: he got a wonderful sound, with those cymbal crashes and the bass drum going. It’s a sound on every Blakey recording. Connie Kay used to have one of those beaters, too, and Lester Young used to call that beater a powder puff. Connie would tap it like that, too.

EI: It’s pretty mysterious. I heard Billy Hart sometimes and swore he was feathering, but then I watched his foot and he wasn’t.

AH: Exactly! There’s something going on in the whole that makes you feel that. Billy’s tricky, man. He knows what he’s doing.

I find that swing is really hard to do. You’ll have a nice feeling for a moment but then somebody on the stand messes it up. Often the piano player, where he puts his left hand, it’s…It’s OK, but…Piano players get carried away, just like drummers. They are more concerned with the harmony and not enough concerned with where they play that harmony in the rhythm. That’s why the way that Count Basie played the piano was so special, or the way Abdullah Ibrahim or Ahmad Jamal played. Red Garland’s left hand was either on or off the beat, in a clear way, and the drummer could play off those anticipated beats.

You leave space, too: I heard that last night. That lets me and the bass player – last night it was Ben – we can keep it right there, keep the beat consistent, and at a volume where you don’t need to bang to be heard. It gets real smooth and starts to flow. And everybody feels it, not just the musicians, but the people in the club, too.

EI: I guess I think pianists can overplay in the left hand. If you’re not playing an ostinato or stride, why not just keep it light and listen to the bass and drums?

AH: Drummers can play too much in the left hand too! It becomes a battle.

EI: I tolerate it more from the drummers than the pianists!

AH: During that battle, the bass player just starts ignoring both of us. And then sometimes he gets really busy, with their “diggety-booms” and the bass bombs! Then you got 4 or 5 guys up there, everybody’s dropping bombs – you bomb everything out, it’s blown up!

EI: Your brother never got too busy. Ben and I talk about how the best recorded bass playing with Charlie Parker is the studio date with Al Haig and Max Roach.

AH: Wow!

EI: Also, you and Percy lay a smooth carpet down together on The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery.

AH: I like that record, but you know that was the only time I played with Wes.

EI: How did you end up on the date?

AH: I can’t remember, maybe Orrin Keepnews called me when Philly Joe Jones didn’t show up or something. That’s what Art Taylor said, that his whole was career was based on Philly Joe not showing up. But they kept calling Philly Joe, since if he did show, they knew that they were going get something special. Philly Joe played piano, too, like so many great drummers. Kenny Clarke could play piano, but he was really into vibes until he heard Milt Jackson. When he heard Milt he said, “No more vibes for me!” Anyway, apparently Philly Joe could play his ass off at the piano as long as it was in the key of F.

EI: We call that “The people’s key.” Bb is a little hard, but F is just right.

AH: That’s the one. I can stumble around in it myself. I don’t need too many “accidents,” that’s what I call accidentals! If you don’t see them coming it’s definitely an accident.

EI: You just mentioned Milt Jackson. Tell me about playing with the Modern Jazz Quartet.

AH: I did a world tour with them the last two years they existed. With John Lewis, “Less is Best.”

Percy told me that in advance, and it was true. I understood it when I got in that seat. I could see how Connie Kay adapted to fit into John’s concept of how the music should go. Connie did such an excellent job of playing John’s music. Kenny Clarke quit the quartet because of how there wasn’t enough activity for the drums. “I gotta play the drums, man! I can’t hold back like this all the time. It’s not jazz: I’m outta here.”

But Connie was perfect. Connie was on staff at Atlantic Records on the R&B side, which meant that he had a beat that was ridiculous. Then he could apply that knowledge to the Modern Jazz Quartet music, but down about 50 decibels!

John’s music was not easy, you know. The first gig I played, we played all the stuff I heard my whole life. I sat there like I was Connie Kay myself! But the second gig, here at the Blue Note in New York, John wanted to play some of the extended pieces like “A Day in Dubrovnik.” Milt was always argumentative, wanting to play his blues and all that. Milt and John were always in conflict. Percy always thought that John had made Milt – and had made Connie and even Percy too! – because of John’s original music, not because of those blues pieces Milt wrote.

Milt never wanted to play the hard John Lewis pieces, but John would insist, like when we were in New York, saying that people wanted to hear this music. Milt was pissed, but John got his way.

At the rehearsal, John gives me this book. Wow! I can’t even look up: I need to watch this motherfucker close. I get through the rehearsal OK, since in addition to the written parts, there was a lot of space and keeping time, thank goodness.

Milt’s part, though, was ongoing the whole time. I didn’t see a single rest in that score! There was page after page after page of the shit. Milt looked at it once and put it away. We came back and played it that night. Milt was pissed at having to play this piece, but he didn’t miss a thing or play any wrong notes. This guy had the capacity to look at written music once and know it cold. Milt Jackson had a photographic memory and perfect pitch. He was a freak!

Then, when John was soloing, Milt came over to me and started talking. “Yeah, Bubba, I see you got the rug underneath the drums tonight,” and all that shit. I told him, “Man, I can’t talk while playing, I’m worried I’ll get lost,” and Milt got so mad he wouldn’t talk to me for three days.

EI: Come on.

AH: It’s true! But that’s not as bad as what happened this other time. Milt really got mad when I got in the wrong limo. The MJQ traveled in two limos. John and Percy rode together and Milt and Connie were together in the other limo. That’s how Milt thought it was supposed to go, and when I got in the limo with John, I think he didn’t speak to me for three weeks!

Two separate limos! Also, they asked for the four corners in first class, to be as far from each other as possible. These guys did not get along. Until they got onstage, when it was phenomenal. Well, they would play cards up until showtime. During the card-playing they would get loosened up, start laughing a bit. But after the gig, bam, they were strangers. Amazing! Forty-two years of this bullshit.

EI: I would have quit the band.

AH: Yeah! Most people would. Well, Milt did quit a couple of times.

EI: I guess the bread was too good for him to stay away.

AH: The money brought him right back. Oh, he hated it. He hated John Lewis. He was very envious.

[Tootie pauses to order a beer.]

AH: The best beer I ever had was in Prague when I was there with Ron Carter. We were there to play with Frederick Gulda.

EI: Oh, no, that must have been a drag.

AH: Gulda was nuts! And he wanted to play jazz. Oh, how he wanted to play jazz, so badly…

EI: I’m sorry to be negative, Gulda obviously had amazing talent. But he seems like a tourist when he deals with jazz.

AH: He was very arrogant and very insecure.

EI: There I have sympathy: playing with you and Ron? Who wouldn’t be insecure, Christ.

AH: I also went to Brazil with Gulda and Jimmy Rowser. It was supposed to be what we did in Eastern Europe: the first half solo piano classical music, the second half with the jazz trio.

EI: Well, I hope you got paid.

AH: Oh yeah we got paid! Really well. In fact, in Brazil they didn’t want us, they just wanted Fredrick Gulda, so Rowser and I hung at a great hotel for two weeks with a pool and everything and still got paid well without even having to go the gig!

EI: When was this?

AH: Early sixties maybe.

EI: Of course you and Ron Carter were playing with Bobby Timmons around that time.

AH: Now that was fabulous, man. Every time I see Ron we immediately start telling each other the Bobby Timmons stories. He says, “Man, we had a nice thing, didn’t we?” And I say, “Yeah, Ron, did you ever listen to the record?” and he says, “I do all the time!”

EI: It’s a classic record, live at the Village Vanguard.

AH: Bobby was struggling with his addiction. It was the height of his popularity as a composer of “Dis Here” and “Dat Dere.” He was getting a lot of attention. So Orrin Keepnews arranged a tour for us with Riverside Records backing it.

Bobby was trying his best to straighten his life out and get rid of his addiction. So he lied to me and Ron. He was a chronic liar, which had something to do with his addiction. We told him, “Man, we don’t want to go to San Francisco if you are strung out and sick and can’t play and all that.” “Oh no, I’m cool! I went to the doctor and got this bottle of dolophine pills.” Heroin addiction is very painful: your hands ache and everything, and dolophine was supposed to suppress the pain.

So we get on the plane, and we are all happy. Bobby’s going to get clean, we’ve got a great band, the press is waiting, the records are selling: great! We even had little uniforms. In these green jackets me and Ron – both young and handsome – we were sharp!

Unfortunately, on the plane, Bobby took all of the pills at once and starting drinking vodka. He started feeling the pain, I guess. So by the time we get to San Francisco he was out of it! We check in the hotel and Bobby hooks up with this guy Jason. I don’t know if Jason was a supplier or an addict, but we had an adjoining room. We thought we had gotten Bobby safely into bed but this Jason shows up. Bobby obviously couldn’t use anything, since he was already poisoned with everything, so I don’t know exactly what was going on. It was time to go to soundcheck, and Bobby said he’d meet us there.

The club owner greets me and Ron, we set up, and finally it’s time to play. No Bobby. The club’s full and the owner says, “You and Ron have to do something, I don’t want to give any money back.” So Ron and I play the first set duo. We’d played everything we could possibly play duo while staying in the context of the Bobby Timmons trio! We didn’t go nuts, we played the tunes. We both soloed a lot, of course. I played everything I knew on the first song, really. My shit was over even then.

After that was done, on the break: still no Bobby. When it was time for the second set we went up there again to try it some more. While we are playing Bobby finally comes in, and he and the club owner go into the back room behind the bandstand together. They had some words, you know, and the next thing I know Bobby comes out with blood all down the front of his green uniform. The owner had punched him in the nose and fucked him up. Bobby told me and Ron, “Pack that shit up. We are out of here.”

That was our grand opening on the West Coast.

The club owner later said that Bobby came at him with a knife, and Bobby did carry one, I know that, since Bobby pulled it on me a couple of times. The owner said he popped Bobby on the nose to protect himself. And, actually, Bobby and the owner settled whatever it was and we went on to play the two weeks.

Ron would always push me to negotiate with Bobby since Bobby and I grew up together. When we got to Detroit, after two nights at the club, the hotel was demanding some money to keep staying there. We hadn’t given them a dime yet. Ron said, “That’s your man. Go tell B.T. we need some money!” So I’d go over and say, “Bobby, we need some money.” “Okay, man. I’ll get some tonight.” He’d say that all the time but every night, after drawing the money, he’d leave with this dope dealer and go shoot up somewhere. On the third night, Ron says to me, “Tell your man if he doesn’t give us some money they are going to throw us out of the hotel!” So I confronted Bobby again and that’s when he pulled a knife on me in the dressing room. I got scared: I saw the rage in his eyes. “If you ask me again…”

But then he did give up some money that night and we gave it to the hotel.

The music, though, that was all fun. I loved playing with Bobby Timmons and Ron Carter. The intrigue before and after the gig, though, that was a problem!

I remember when Bobby was dying at Saint Vincent’s right across from the Vanguard. I went in to see him. He was all tubed up and shit. “Hey, Toots, what’s happening? Yeah, I’m getting out on the weekend. ”

I went outside the room and the doctor said, “Can I speak to you a minute? Are you a close friend?”

“Yeah! Bobby Timmons and I grew up together, he was around the corner from me and then we went to school together. I’ve been knowing him my whole life.”

He said, “He’s not getting out on the weekend, and if he is getting out on the weekend, it’s going to be in a box, because his liver is like a sieve.”

So Bobby was lying all the way until the end! His son tragically committed suicide in his twenties, I never knew him though. I knew Bobby’s wife, of course, since we all were in school together.

EI: Who else did you go to school with?

AH: I’ll never forget when Jimmy Garrison came up from Florida. He was very country, with thin and colorful clothes – flowery shirts and such – that were way out of season for Philadelphia, where it was cold as hell. We used to laugh at Jimmy Garrison. In Florida, Jimmy was a singer in a quartet like The Orioles. So when he hooked up with me in high school, somehow he got to my house because he knew I was into music. When he came over, he saw Percy playing the bass, and that was it! He started playing bass.

EI: Jimmy Garrison started playing bass because of seeing Percy practicing at your house?

AH: Through his whole career, Jimmy said that Percy was the guy that started him off.

EI: Did you play with Garrison much besides those three tracks with McCoy Tyner on Today and Tomorrow?

AH: I called Jimmy once for a gig uptown at a place called Mikell’s. This was after Coltrane died, and I thought he might want to make the hit. I said, “Damn, James, can we do a gig together?”

He said, “I’d love to make it, Tootie, but after playing with Coltrane for so long, I don’t know any songs! After seven years of vamps, I forgot all the tunes!” I thought that was some funny shit. Of course, the way Elvin played so loud and rumbled through everything, you couldn’t hear those vamps anyway!

EI: Did you play with Wilbur Ware at all?

AH: Yeah, I did. Just a few times at jam sessions and in lofts. Guys like Wilbur Ware who had no place to stay, you could often find them hanging out and begging! But he was one of the greatest, though. Like Bobby, he fought that addiction.

EI: You’re on so many records with so many great people. Billy Hart told me about a fabulous Yusef Lateef quartet with Kenny Barron and Bob Cunningham that I don’t think was documented properly.

AH: We were in there about eight years! I did about eleven years with him: after Kenny left, Danny Mixon played piano, and there was an electric bassist named Steve Neil that took Bob’s place. There’s about three Lateef records that I’m on. Yusef was always searching and trying to do different things. We used to have one-act plays in the club! We’d be running all around, and the audience would say, “What the hell is this?” Yusef is a very interesting man. He’s in his eighties now but hasn’t stopped yet.

EI: I’m not sure, but there doesn’t seem to be a record of that quartet that doesn’t have heavy studio overdubbing. Is there one of those you especially like, anyway?

AH: I like The Gentle Giant, but it’s out of print for sure. There was some different people involved in that, too. But Yusef let me play flute on it, I remember that. He always pushed every one of us to compose and play other instruments, and also advocated going to school.

Yusef taught a composition and arranging class here at City College in New York, and encouraged us all to attend. We all did, we registered and everything, and Kenny went on to get an undergraduate degree. I was discouraged because the class was in atonal music. I wanted to write songs, not deal with atonal music, tone rows and all that, where the notes don’t repeat until you use them all. Donny Hathaway was in one class. He came one time and got the assignment for the term project. I did a string quartet and Donny Hathaway did a brass ensemble. For the recital students played all our little pieces and Hathaway’s was the best by far! I can still hear this music Donny Hathaway wrote for brass! It was incredible, and he didn’t even come to hear it played that one time.

EI: So there’s a Tootie Heath string quartet out there?

AH: Somewhere. Atonal stuff, pretty wild. But Donny took that atonal concept and made it musical, more then the rest of us. Even Kenny Barron couldn’t do that.

The songs on my second record with Kenny Barron came out of Yusef’s class.

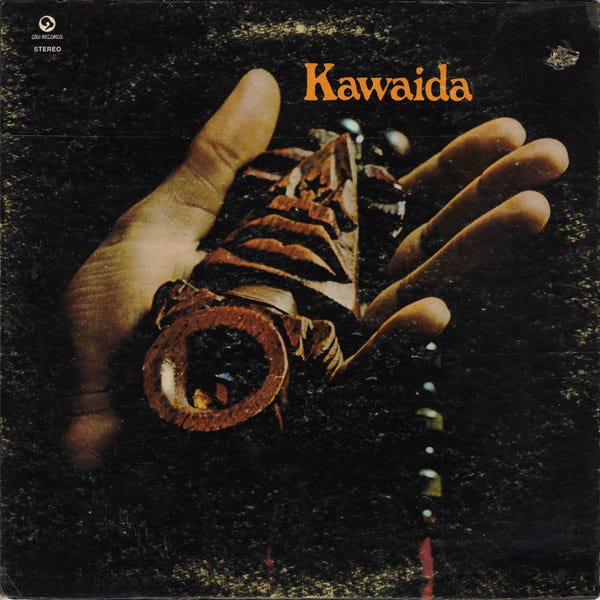

EI: You aren’t associated with the avant-garde that much, but your first record has Don Cherry on it. I think that’s the only meeting of Herbie Hancock and Don Cherry, actually.

AH: Kawaida.

My nephew, Mtume, was in an organization called US which was a counter-organization to the Black Panthers. It was a black nationalist group interested in Nigerian culture, religion and the history of the African-American people. Mtume was involved with them and for a time followed the teachings of Maulana Karenga (now Dr. Karenga; he’s out in LA). We learned about Swahili and that we should rename ourselves since our given names are slave-owner’s names.

When I had the opportunity to make a recording, I got Mtume involved and he came in with the music and poetry. He also named everybody: that’s when Herbie became Mwandishi. I was Kuuamba.

I don’t remember what he called Don Cherry, but I know Johnny Griffin named him “The Traveler,” since Don Cherry could show up anywhere in the world, surrounded by strangers, playing his little trumpet. It could be an airport in Istanbul, he’d just show up. The next week you’d hear that someone just saw him in Pakistan, again surrounded by people and playing the pocket trumpet.

EI: Did you call Don for the date?

AH: Yeah. Don has always been my hero as far as trumpet was concerned. I like two trumpet players: Miles Davis and Don Cherry. Of course there are others but those are my heroes.

Now, one of the reasons I loved Don Cherry so much is that he knew how to play conventionally, but he chose not to. He found his own voice. Him and Ornette Coleman together, with Charlie Haden and either Blackwell and Higgins, that was my favorite music. Don and I lived in Stockholm together for some years, too.

EI: Don’s the highlight of Kawaida, for sure.

AH: Oh, man! He could play. One time we went to Europe together, in George Russell’s band. That Lydian Concept, man, a lot of the time it sounded like you just sat on the piano at that was it: every note at one time, instead of real chords. I hated it. But Don came and played all of George’s hard music like it was nothing, and then played incredible solos on it. In France they booed us after that arrangement of “You Are My Sunshine.” I’ll never forget that! We played it in twelve, and everybody played the melody in a different key, and the French said, “BOO!”

EI: It sounds like I would dig that arrangement!

AH: It wasn’t for me.

EI: It’s interesting you had such a positive reaction to Ornette. Not every straight-ahead musician did.

AH: Compared to George Russell, Ornette Coleman was Guy Lombardo!

I used to live on Fifth Street between Bowery and Second Ave. Tons of musicians were on the block: Elvin Jones, Joe Farrell, John Hendricks, Ted Curson, Bobby Timmons, Lee Morgan… We used to go on the roof, get high, and have jam sessions. And around the corner on Bowery and Third was the original Five Spot, where Ornette would play every night for months. We’d walk around, smoke a couple of joints, and say, “Hey, let’s go listen to the Cold Man.” We called Coleman “the Cold Man.”

At the Five Spot, everybody in the place was high, and at first, the music seemed real out. But after awhile…Billy Higgins was the one who helped me begin to understand that: “Hey, man, these guys are actually playing together. I don’t know what it is, but they’re together.” I loved it. Ornette didn’t count off anything, didn’t tell anybody any changes, he would just do it like this: “Boom!” They’d start, and be in the song, together. I was amazed by Ornette.

I saw Sonny Rollins in there a lot, hiding in the phone booth, checking out the music but not wanting to be seen. Trane was down, Lewis from the MJQ. Everybody started coming down.

Percy was the one that kind of got me on Ornette. He brought me the record that he’s on with Ornette, saying, “This is some funny stuff these guys play!”

I loved some of the phrases Ornette played, they sounded like he was saying things, which he was, so I made up little sayings that went with the music. I know in that interview, Billy Hart said I made up words to whole songs, but that’s not really true, it was just some phrases.

But I did love Ornette, especially with Charlie Haden and Don Cherry. Blackwell and Higgins each had their special magic.

Higgins could play anybody’s drums and still sound like Higgins. It could be a huge bass drum and the wrong kind of snare, but he could sit down and start swinging right away. There was some happiness in his playing that related to his beat. He had a great ride cymbal beat that was consistent, that never stopped, no matter what else was going on.

Blackwell had the New Orleans street stuff that he could incorporate into swinging. He’d play swing for a while but then he would leave it, and with Ornette he could do that. He was a master of swinging, leaving it, and coming back to swing. One of his signature things was something that sounded Nigerian, too.

I called Blackwell alongside Cherry for that same record with Mtume. I had him on there with Don. I would have had Ornette too if I could have paid him enough!

EI: Kawaida is a record of grooves, with nothing swinging. You played a lot of grooves with Herbie Hancock and others in that era, too. In fact, you are one of the few guys that played the real bebop with the masters in 1960 and then the new groove languages with the cats in 1970. Not everybody could – or was willing – to do that.

AH: I always try to look around and see what’s important in the time. Like now, hip-hop is very important, and I pay a lot of attention to it. I pay attention to the beats and what they are saying. It’s the music of this generation.Its influence is unbelievable. You go to Paris, and you see these kids with their pants around their ankles and their hats sideways. That’s prison stuff, man, they take your belt away so you don’t hang yourself (or somebody else). And you put your hat on backwards because you know you aren’t going forward.

So I paid attention to Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, and Sunny Murray when it was their time. Or the way Mingus talked about the Civil Rights movement in his music. Or the way Herbie and Yusef played the groove music in the late 60’s and early 70’s. In true forms of art you need to express the time. You can just be self-involved or you can try to deal with the world.

Hip-hop started in the community, in the hood. They took the instruments out of the schools? Ok, we don’t need no instruments: we’ll start scratching, and make music that way. It’s important to have a spectrum. Coltrane used to say, “When you think you know it all, it’s over.”

I’m very grateful I was in Coltrane’s early life. We were in a group together called the Hi-Tones with Shirley Scott on Wurlitzer and her husband Bill Carney, who sang, played some conga, got the gigs, and drove.

John and I had to lift that heavy-ass organ and put it the truck. We hated that! The Hammond was in two sections, but this Wurlitzer was in one piece. Horrible! Shirley played that because then you couldn’t look up her dress. (The Hammond B3 was open.)

We had that group for a long time around Philly, and I remember John playing kind of like Sonny Stitt and Dexter. He was the ultimate searcher. He would practice all day and fall asleep with the horn in his mouth.

EI: But you’re not a fan of the classic quartet with Elvin?

AH: Not really. It was important at that time, but I thought Elvin played too loud sometimes. Of course it did get exciting…and long! Man, they played one tune for 40 minutes.

EI: There’s two other tenor players I want to ask you about while we still have a second. You played a lot with Warne Marsh in California.

AH: Wow! Warne Marsh was amazing. He was always, always, always high. And to play with him, you needed to be high yourself or be sober for a week in advance. Otherwise you’d be lost playing with him. Lennie Tristano put a hurting on Warne Marsh. Tristano was great! We don’t talk about him enough. But Marsh had a hard time getting away from thinking about Tristano. Great tenor player, though.

EI: And you played on the last Sonny Rollins live stuff from Denmark in the ’60s, before Sonny left music for a while. Speaking of forty-minute tunes, that forty-minute version of “Four” is legendary.

AH: That was a hard gig. This is what I felt about Sonny Rollins: that he could play anything I played back at me, twice as fast and twice as good. During the first chorus I would play the hippest stuff I knew, but then Sonny would make mincemeat of that and keep going. What a musician. What a career.

Wow! What great interview!!

Ethan, fine interview. A treat to read through that history.