The great concert pianist Russell Sherman passed away in October at the age of 93. Excellent obituaries appeared in the NY Times by Vivien Schweitzer, the Washington Post by Harrison Smith, and the Boston Globe by Jeremy Eichler.

Before the year ticks over into 2024 I am quickly publishing three posts. Often my writing is a kind of diary, where I make connections and memories public. I never met Sherman, I didn’t see him live, nor am I any kind of an expert in his complete discography. But he touched me quite deeply in a few ways.

Interview with Gunther Schuller and Russell Sherman/The Not Quite Innocent Bystander: Writings of Edward Steuermann/pedaling/Chopin/Beethoven

Russell Sherman suggests Cramer études for me and my students

Roger Sessions as played by Randall Hodgkinson, Ralph Shapey as played by Russell Sherman

Upon arriving in New York I started hanging out at the Bobst library at NYU. Pat Zimmerli had gotten me interested in atonal music, which meant Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg’s pianist was Edward Steuermann (truly amazing Wiki entry: premiered many major works, taught many important students, sister wrote scripts for Greta Garbo) which led me to The Not Quite Innocent Bystander: Writings of Edward Steuermann.

The year was maybe 1992, and the book had been published in 1989.

Most of the book was over my head, and to be honest I’ve never paid enough attention to Steuermann’s original music (written in the Schoenberg lineage), but one section I read and re-read over and over: two Steuermann students in conversation, Gunther Schuller and Russell Sherman.

After Sherman died I looked at the pages again and realized I could recall many of the words exactly.

In this excerpt, Sherman and Schuller explain a bit of how Steuermann put it all together with Chopin at the center.

Russell Sherman: As for his piano teaching and the choice of repertoire, to me it is uncharacteristic that he depended so much on Chopin to teach the piano — rather than Mozart, Haydn, or Bach, a nexus to which you would think a serious intellectual would devote himself. But I think he felt that playing the piano was a very individual task that dealt with a very strange concoction of hammers and actions and felts and bushings, that required tremendous suppleness and suavity. Also, the balance of the hands was for him tremendously important. So also the whole quality of transparency and how to create linear strands within heavily heterogeneous homophonic music, as in Schubert; and how to treat the pedal, which after all is the most important thing in Chopin. And the thing one learned from Steuermann was that you could use the pedal without creating a trough — is that the word? — of sound where everything fell into this pigpen, but that the pedal was just a subtle coloration to bring out any particular important detail. He checked off that infinite number of pedal calibrations. To play, for instance, a staccato through the pedal was no problem at all for him, which nobody can do nowadays. I try to explain this to my students but it seems to be an absolutely unknown territory.

Gunther Schuller: Yes, I remember he dwelt a great deal on that in lessons that I attended and I have a funny feeling that his was a relatively new concept of pedaling which I think he worked out in connection with Schoenberg's music — to bring out the needed harmonic and textural clarity in the music.

RS: He used to certainly feel that Schoenberg's piano music was extraordinary just for its piano style. He always had the greatest admiration for just the way Schoenberg's piano music picked the finest scents and perfumes out of the instrument. I do believe that there was a relationship there, as you suggest. On the other hand, I am aware of a book Anton Rubinstein wrote, called eighteen (or twenty-eight or thirteen) ways of using the pedal. It may have been something that was at one point much more featured and investigated, and somehow the modern piano with its voluminous sounds sort of killed instinct for differentiating and treating the transparencies through the pedal. And that's a great loss in a way. That's why people nowadays are very mystified in some sense about what is the right piano to play music on, any music; and what's the best piano and why. There is, for example, a certain return now to the German Steinway, which is considered less “bulky” and “rhapsodic” than the American Steinway, and I think there will be increasing fascination with Bechsteins and Bösendorfers and other European instruments.

GS: But this use of the pedal was dedicated primarily to what purpose? Was it on the one hand harmonic clarity and on the other hand linear clarity, I.e., polyphonic clarity, even in homophonic contexts: bringing out the lines, the voices, the voice leading?

RS: Exactly; that's why I think he went to Chopin so much. Even though you had these radiant harmonies that were so intoxicating at that saturated the sensation, the aesthetics, so pleasantly, you could still evince specific notes and voicings. I know — and I know it’s the legacy of Steuermann — that I always wanted to write an article for some magazine, called “Chopin: Master of Counterpoint.” It's a counterpoint of textures, rather than pictures, as well as individual voices and hidden in her lines.

GS: Steuermann also taught Schumann a lot, and maybe for some of the same reasons.

RS: Schumann was in a certain sense to him the closest to his own quality of soul, his own generosity and his own feeling terminal anguish and sadness of the music.

GS: I remember when he was teaching Schumann — and this is ironic because he is regarded by many people as a rather poor orchestrator — he treated Schumann’s piano music very orchestrally. He was always talking about the orchestral colors in the specific instruments: the horn, the viola, the clarinet, the oboe, and so on.

[…]

GS: I remember rather well his all-Chopin recital at Juilliard, I think in the late fifties or perhaps early sixties. He was very nervous about it, partly because he was a nervous player anyhow — he had a stage-fright kind of nervousness. But also it was his first major recital in a long time. And thirdly, he was tackling a repertoire with which he was not yet associated. Steuermann had been typecast as the Schoenberg expert and subjected to all those kinds of limiting labelings. And here was coming out with Chopin and invading the territory of Rubinstein, Brailowsky, and all of those people. So he was very concerned, very apprehensive about how that would go. It was not technically flawless playing, by any means, but what I remember as a young composer and still very much in formative years was that he completely transformed Chopin into the richest kind of harmonic language, full of wondrous dissonances, which was an association I certainly had never made with Chopin, and indeed I had never heard his music played that way. He brought out things which most Chopin specialists seemed to gloss over or hide. Most people play Chopin with a sort of attractive sonic patina, a glow of colors and very pianistic…

RS: Gloss and legato…kindly and tender…

GS: But he brought out the dissonance factor in the music…

RS: The demonic element….

GS: Yes….that made it late-Wagnerian in its remarkable chromaticism. I think he wanted to show how incredibly advanced, harmonically and melodically, Chopin was and that this was rarely brought out by other pianists — starting probably with Paderewski and that generation of Chopin pianists. So his performance was like a statement against that kind of performance. Do you recall anything in his teaching that respect?

RS: Only in the sense that the inner voices were always contrapuntal, subversive to the fundamental roots at the top melody line. And this intrigued him a great deal. And in general everything that was subversive [laughing] intrigued him. He was interested in every detail, not because he was such a perfectionist (which I think every decent musician is), but because he had this essential egalitarian spirit, that nothing should be forgotten. Everything I had a soul; and through him I think I developed my own particular concern for dynamics, caring about every note, and so on.

The thing that I feel is most characteristic of his playing and his approach, and which, to me, is transcending and is felt deeply through his whole legacy and school, and through the people who know that school but have very rarely spoken about it in appropriate terms — because it is somewhat mystical — is what I would call — and this is again somewhat lost — the “leggiero” school of playing, which permitted a tremendous amount of combustibility and volatility and expressive energy, offered without saturating the musical canvas, so that ideas could really rebound against each other and interact and be playful. There was this quality of play — which reminds me that he used to say very frequently child playing is a sport. He didn't say it just for my benefit [laughing] because I was a dumb jock, I think he really believed in the sheer activity and the beauty manifesting itself — a form of physical energy — that was connected to the piano.

But for Steuermann the quality of sound — what was at its center — was the capacity, the need to sing. And I once asked him in the worst painfully simplistic way, and totally against his character (and since I was trained by him, totally against mine at that point), “Well, what is the most important thing?” I wanted the secret of life, you see. “What is the secret of piano playing?” And he offered an answer — to my astonishment — which was: “Cantabile” — that it must sing. That was the fulcrum around which everything else was suspended, and that “everything else” was extremely mischievous. His playing had a great deal of “fountain play” in it, and I believe the pedal was that form of mediating the capacity for things to glide and slide, smoothly, but at the same time to admit these radiant individual sparks.

(…)

RS: Now that I think about it, there is a certain Brahms Intermezzo in C-sharp minor — a painfully beautiful music — in which towards the end the coda is a statement of the theme in in its most miraculous cast, with a sort of heaving harmonic addition, and a left hand that breaks from bass to tenor. And there he said to me a concept that I simply hadn’t heard see formulated anywhere: “Diminuendo in the pedal.” And I remember the sensation when I tried that, how this enormous sound of deepest cri de coeur would be gradually released and move into a sort of spatial levitation. (EI: I have pondered this passage at length, and have concluded that Sherman must mean not the coda of the C-sharp minor Intermezzo, but rather the middle section in A major.)

(…)

RS: Yes, his use of the pedal had a phenomenally sophisticated quality that I think was unique.

At the time of first seeing these words some 30 years ago, I had no perspective whatsoever. I believed what I read!

Today I’m more skeptical. In particular, I am critical of Schuller putting Steuermann in opposition to the lesser (?!) Chopin pianists Paderewski, Rubinstein, and Brailowsky. He is protecting his mentor, but I highly doubt that Steuermann had something that other great midcentury pianists didn’t.

Schuller’s comment that Steuermann was not at ease as a performer seems more correct. Steuermann didn’t record any Chopin, but he did make records of Schoenberg and Busoni. Those records aren’t overwhelmingly impressive, they are a bit uniform and stodgy, although of course they will always be of historical interest since Steuermann worked with both.

Many significant artists embrace the advice of their early mentors, even if those mentors were underpowered or just plain wrong. After all, one needs to start somewhere. Schuller and Sherman are right to celebrate a key teacher, their living link to Schoenberg, but it’s a bit provincial to place Steuermann so very high in the pianistic firmament at the expense of other contemporaries even greater than Steuermann.

Still, the detailed comments about pedaling less have always stayed with me. While listening to Chopin performances over the years, I always dock a point or two when everything is pedaled in a uniformly thick manner, “gloss and legato” as Sherman describes. Certainly the early sensational records of Josef Hofmann and Ignaz Friedman have distinctive pedaling, often shocking in their dryness. For that matter, the very great Artur Rubinstein (lumped in with Paderewski and Brailowsky by Schuller above) had all sorts of wonderful pedal finesses (including dryness) that Rubinstein applied to Chopin. So too did Vladimir Horowitz and probably any other famous midcentury pianist.

Russell Sherman’s own recordings range from solid to inspired. Just about the finest studio performance of standard repertoire I’ve heard is the Chopin Barcarolle. (YouTube link.) Part of the magic is the lack of thick pedal. Sherman is quite risky, controlling the counterpoint, interweaving the voices, and letting the cantabile pilot in waters that are not always that smooth.

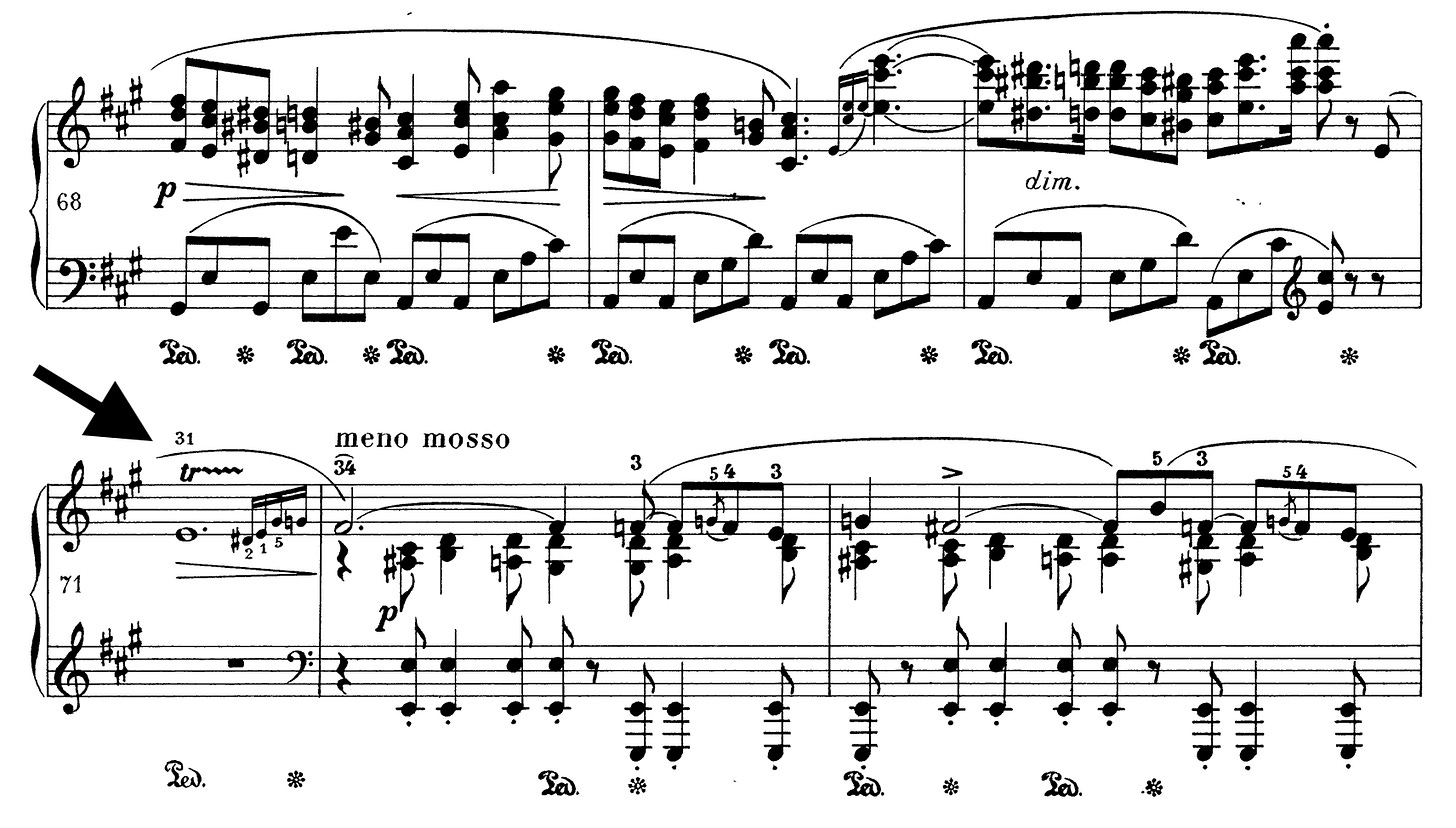

At 5:20, Sherman starts Chopin’s long trill (bar 71 marked with arrow below).

The trill starts under pedal (naturally enough), but then Sherman slowly lifts up his right foot. After the trill becomes “dry,” the meno mosso chords that follow are also dry. It’s quite stunning and, as far as I know, unique.

Undoubtedly every other recording of the luscious mid-tempo Barcarolle made in the last 40 years has far more pedal than Sherman. I am praising the midcentury pianists like Rubinstein and Horowitz, but to my taste Sherman’s contemporaries (and those even younger) have often had trouble finding their way in Chopin, mainly because they can be too correct and impersonal.

Sherman’s Barcarolle makes good on what Sherman describes to Schuller about Edward Steuermann:

…The “leggiero” school of playing, which permitted a tremendous amount of combustibility and volatility and expressive energy, offered without saturating the musical canvas, so that ideas could really rebound against each other and interact and be playful…

…“Cantabile” — that it must sing. That was the fulcrum around which everything else was suspended, and that “everything else” was extremely mischievous. His playing had a great deal of “fountain play” in it, and I believe the pedal was that form of mediating the capacity for things to glide and slide, smoothly, but at the same time to admit these radiant individual sparks.

The student does what the teacher said to do, but in this case I suspect the student far surpassed the teacher.

I started working for the legendary choreographer Mark Morris in about 1997 or so. Mark talked about how much he loved Russell Sherman playing the first Beethoven concerto, so I borrowed Mark’s 1986 Pro Arte CD with Václav Neumann and the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra.

I was advised to pay attention to the Rondo, that the phrase lengths were unpredictable, that “some of it went on too long." (Mark meant this as a compliment, of course.) After listening, I had to go find the score to figure it out: Ludwig van writes phrases of 6, 8, and 6.

This was a key moment. I basically liked Beethoven (and Mozart and Haydn everybody else in that area) but all of a sudden I started hearing how the longer phrases interacted with each other in a new way. What was very old was suddenly incredibly fresh.

It’s still fresh. This Russell Sherman recording of a Beethoven rondo gave me the answer for a lifetime.

addendum:

I’ve just learned that Edward Steuermann recitals of C.P.E. Bach, Weber, and Schumann from 1959 and 1961 are available on YouTube. While hardly note perfect, they sound relatively healthy, communicative, and personal. Indeed, Steuermann goes some distance towards turning C.P.E. Bach into Schoenberg, which was surely his intention. This gives a bit more credence to Gunther Schuller’s bold suggestion that Steuermann, more than other pianists, made Chopin “incredibly advanced, harmonically and melodically.” (I still would not put Steuermann up against Artur Rubinstein in Chopin.)

Bruce Brubaker recorded the intriguing Steuermann Piano Sonata, which can be heard on YouTube. Allan Kozinn reviewed a 1990 Brubaker recital in the New York Times.

Obviously, as shown by the interview, Russell Sherman speaks beautifully about beautiful music. There is much more in the interview with Gunther Schuller in the Steuermann volume, although the place to really sink into Sherman’s worldview at length is the 1997 book Piano Pieces.