The Billy Hart Quartet with Mark Turner, Ben Street, and myself plays Smoke Jazz Club, Thursday through Sunday, December 7 through 10. It’s our first time at this great venue.

Billy turns 83 today. Vinnie Sperrazza has been writing up his earlier albums as a leader, Part one, part two. Thanks Vinnie!

Here’s another excerpt from the forthcoming Billy Hart memoir, about John Coltrane:

When I first started learning about this music, my favorite tenor saxophonists were inspired by Charlie Parker. Johnny Griffin played bluesy and fast, then I was impressed by Sonny Rollins.

John Coltrane captured me during his solo on “All of You” from Miles Davis’s ‘Round About Midnight. I’ve talked to Gary Bartz about this, and he felt the same way: “All of You” made us John Coltrane fans forevermore. When I first saw John live, it was through the fan blades at the Spotlite room with Miles. John was back from being with Thelonious Monk, doing that “sheets of sound” or whatever they called it. I watched it happen. John would use a lot of notes, a lot what he played came straight from Charlie Parker, but he also always sounded like a romantic singer -- a pure rhapsody -- and of course he never stopped playing the blues.

I love John Coltrane. At this point, I can honestly say that John is my reason. The church is just a building, but that feeling inside a Black church goes back thousands of years. Coltrane – no matter how avant-garde his late music became – “done get you in touch with that.” A single note from Coltrane shows you he’s in command of a universal, spiritual, and philosophical message.

I was waiting for John to form his own band, but Elvin Jones was a surprise. Bassist Wilbur Little had toured with Jones in the J.J. Johnson group in the late ‘50s, and laughingly reported back that J.J. Johnson said about Elvin, “Man, this is either the greatest drummer or the worst drummer I’ve ever played with.”

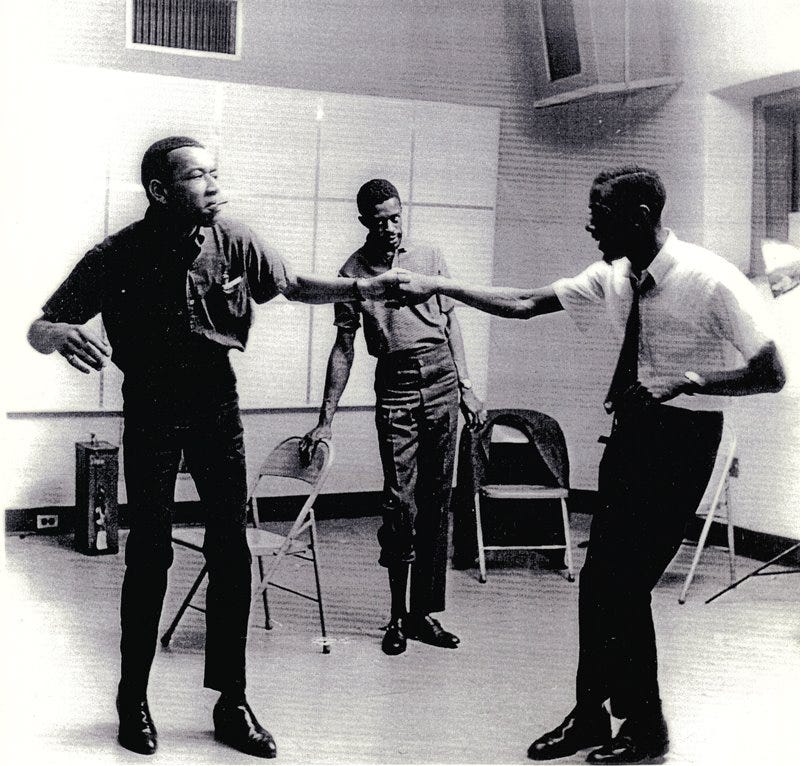

At first this music was for dancing. In the Afro-American community, dancing was very important. I danced throughout high school, we called our get-togethers at our homes “the rub,” as in, “Where’s the rub tonight?” There’s a wonderful photo of Lee Morgan and Bobby Timmons dancing together on the LP jacket to The Young Lions.

(Lee Morgan, Louis Hayes, Bobby Timmons, from the back of the LP The Young Lions.)

Herbie Hancock isn’t that young anymore, but I’m sure if you put on a record of Stevie Wonder or some such today, Herbie would immediately move his body in a certain way.

In dance music, the drums basically have to keep a beat. However, after the so-called bebop revolution, drummers had been looking to contribute to the ensemble in a contrapuntal fashion. It could be hard to do this with most leaders, who wanted their drummers to keep steady time. Kenny Clarke said that he could tell simply by the leader’s expression mid-set if he was going to be able to leave his drums at the gig for the next night, or have to pack them up and go home.

When John Coltrane got Elvin Jones in his band, that was it. The drums were now free. Some of his intensity surely was inspired by Art Blakey. In Trane ‘n Me, Andrew White argues that John simply could not have got to where he wanted to get to without Jones:

“Trane was structuring his music around Elvin. This was the main source of the symmetry in Trane’s music… Breath is life. The music must breathe. Elvin was the breath in Trane’s music. …It was the manipulation of standard devices that established Coltrane as a thorough improvisor as well as a spontaneous creator, but it was the Elvin Jones grammar that brought these elements into clear focus.”

To see Elvin Jones play with John Coltrane was indescribable. I went every night for a week at the Bohemian Caverns. At the end of the final night, I was there looking at Jones taking his drums down. I couldn’t move, like I was stuck in cement. I was just watching him. So finally Jones called me up to the drums, and he gave me his bass drum pedal, which had broken. Jones looked me up and down and said, “Don’t ask me to show you anything, because if I could show you, we would all be Max Roach.”

When Jones told me that, it really made an impression. He was letting me know that despite being one of the most innovative drummers the world had ever known, he saw himself as a representative of a tradition.

I got nervous one matinee at the Bohemian Caverns, because Jones was really late. Was I gonna have to sit in? I went to the bathroom to hide, but I had to pass Coltrane to get over there. I tried to sneak by, but Coltrane grabbed my arm and made me stop. “Aren’t you going to talk to me?”

I said, “What are you going to do about Jones being so late?”

John replied, “I’m not going to do anything, because I don’t want to hurt myself.”

At that time I was listening to the album Coltrane, with “Out of This World” and “Tunji,” two tracks that heavily featured Jones’s style. When I asked John about the drumming on those tunes, John told me, “Sure, Elvin worked on his style. But the thing that impressed me the most when I first heard Elvin was his professionalism.”

When I looked surprised, John continued, “I noticed the way he could dot the I’s and cross the T’s.”

John didn’t say anything about poly-rhythms, innovation or intensity, John talked about the tradition.

John also said, “No matter how tense the situation gets, Elvin never tightens up.”

That was good advice, I have tried to keep that in mind in more chaotic musical settings.

McCoy Tyner was also so impressive. At some point I realized one of the reasons I was going to see the Coltrane quartet was the pleasure of watching McCoy catch up. Not just technically, McCoy always had an immense technical facility, but harmonically. I could see how the band was growing through listening to the piano.

The bass chair evolved in the famous quartet. I first saw them with both Art Davis and Reggie Workman in the band. Later it was the great Jimmy Garrison, who I had seen in a trio with Bill Evans and Paul Motian. The fact that Garrison had played with both Bill Evans and Ornette Coleman suggests some of the qualities Garrison brought to that group. Everyone in the band could “dot the I’s and cross the T’s.”

Some people left John Coltrane at Giant Steps, other people left him at A Love Supreme. Certainly many people left him at Meditations. But I hung in there all the way to the end. I loved the last band with Alice Coltrane and Rashied Ali, and “Expression” from the very last session is one of my favorite ballads.

Later, in LA at the It Club, Coltrane sat with me a minute after his set. A lot of people were walking out, musicians and non-musicians alike. He walked straight to my table and sat down. I said, “John, what are you going to do with everyone leaving during the set?

He replied, “I don’t know what I’m going to do. I just know that I can’t stop.”

When he said that, it was like the whole room turned technicolor and John was a legendary hero in a romantic setting. I told him, “John, you are really beautiful.”

John shrugged and said, “I’m just trying to clean up. Imagine if you were dirty for 30 years.”

I don’t want to sound too dramatic, but this is one of the greatest things I’ve ever read. There are so many answers to so many questions that musicians spend their lives ruminating on...

This is yet another example of why those of us who do not play (or don't play very well) need to listen to the music and words of the masters of Black Music. Billy Hart creates such a joyous atmosphere when he plays whether as a leader or as a group member. Thank you, Ethan, for these delightful excerpts and enjoy the evenings at SMOKE!!