The comments section on this post is open for all readers (usually it is for paid subscribers only). The previous three threads were pretty active and interesting, so: Say what is on your mind, drop your hottest take, or ask me anything — but please keep it clean and civil.

“Kill your darlings” is a famous bit of literary advice. It means, “Get rid of lesser material, even though that material was the product of hard work or emotional investment.”

In my own small career as a prose stylist, “Kill your darlings” has often meant, “Kill your lede.” I can’t tell you how many times I have buffed and polished opening paragraphs before deleting all that time and effort. This is also true of many of my bigger projects as a composer.

There’s no shame in it. I’ve seen Mark Morris spend a week working on an opening section for a new dance before discarding the movement.

Engaging with your creativity is never time lost. Gaining momentum is its own reward. Those that sit at the top table are comfortable with a ruthless edit.

From the Wiki article on the string quartets of Johannes Brahms:

Brahms regarded the string quartet as a particularly important genre. He reportedly destroyed some twenty string quartets before allowing the two Op. 51 quartets to be published. Explaining his progress to a publisher in 1869, Brahms wrote that as Mozart had taken "particular trouble" over the six "beautiful" Haydn Quartets, he intended to do his "very best to turn out one or two passably decent ones." According to his friend Max Kalbeck, Brahms insisted on hearing a secret performance of the Op. 51 quartets before they were published, after which he substantially revised them.

For a few days I thought I had written a hell of a lede for my Louis Armstrong cover story in The Nation. That first draft compared Armstrong’s phrasing to the metronome and contextualized that esoteric concept with contemporary pop culture.

But then my wife didn’t like it. My editor Shuja Haider didn’t like it. Light dawned, and I realized it was just too far removed from Armstrong. It was inside baseball, one for the serious musicians, and the piece needed to begin with a friendlier general overview of Pops. So I killed off my 450-word darling, and began fresh with:

“I get this question all the time,” Ricky Riccardi admitted. The director of research collections at the Louis Armstrong Center looked at me carefully.

Which is quite good, at least when compared with most of my other ledes.

However, since I have my own Substack right here with no editorial oversight, I can egotistically resurrect the original 450-word lede! My darling lives, like a creature from last night’s costume parade!

Take it away, zombie ghost:

In 2023, most music is made to a computer controlled beat, usually called a “click” or “click track.” Every hit has been recorded to a click for decades, whether hip-hop, pop, rock, soul, or anything else. We just lived through the summer of “Barbieheimer." The soundtrack to Barbie is pop songs, the soundtrack to Oppenheimer is symphonic: each cue in both scores was recorded to a click.

The original “click” was the metronome, patented by German inventor Johann Maelzel in 1815. It makes sense that the Europeans came up with the click, because European culture never specialized in a truly reliable beat.

A reliable beat was one element of the culture of Africa. After Africans were brought to the New World on slave ships during the Middle Passage, the two traditions met on unequal terms and created the language that would define 20th-century American music.

Using a click, one can appropriate a superficial level of the African side quite easily. But there is another element to consider: “feel,” where the articulations of rhythm are not so mathematical and quickly supersede basic timekeeping. Some contemporary Americans might use phrases like “clave,” “ahead of the beat,” and “behind the beat” to describe ancient African ideas. Others might simply call this kind of rhythmic sophistication “black music” and leave it at that.

The spiritual predecessor to Barbie was The Lego Movie, which boasts a hit song, “Everything is Awesome.” The official video on YouTube from Tegan and Sara feat. The Lonely Island has 76 million views.

Most of the song is straight-up-and-down techno, which suits the attractive tune perfectly. But halfway through the track, there’s a kind of hip-hop breakdown, and the failure of aesthetics is palpable. The problem isn’t the choice of hip-hop as a genre, it’s that the hip-hop doesn’t feel right.

To fix their black music breakdown, the producers of “Everything is Awesome” should have checked out Louis Armstrong.

Armstrong was surely not truly the first to do behind the beat phrasing, for the science goes back to Mother Africa and all of the Afro-Latin diaspora. But the anointed ambassador of the American mix was Armstrong. As his fame grew, as he became the symbol of American music to the whole world, Louis Armstrong’s beat only got lazier and more confident. He could swing a whole band of the squarest cats all by himself.

Quincy Jones wrote: “It’s a shame that anyone takes him for granted ‘cause everything after John Philip Sousa that swings stems from Louis Armstrong.”

They called him “Pops.” Louis Armstrong: the father.

In this church, we phrase the melodies just a hair behind the time.

The critical/academic approach to the creative arts is a fraught topic. There’s a fine line between knowledgeable and self-important.

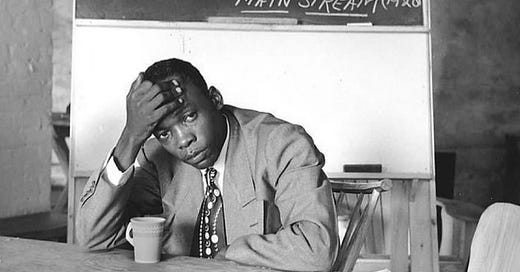

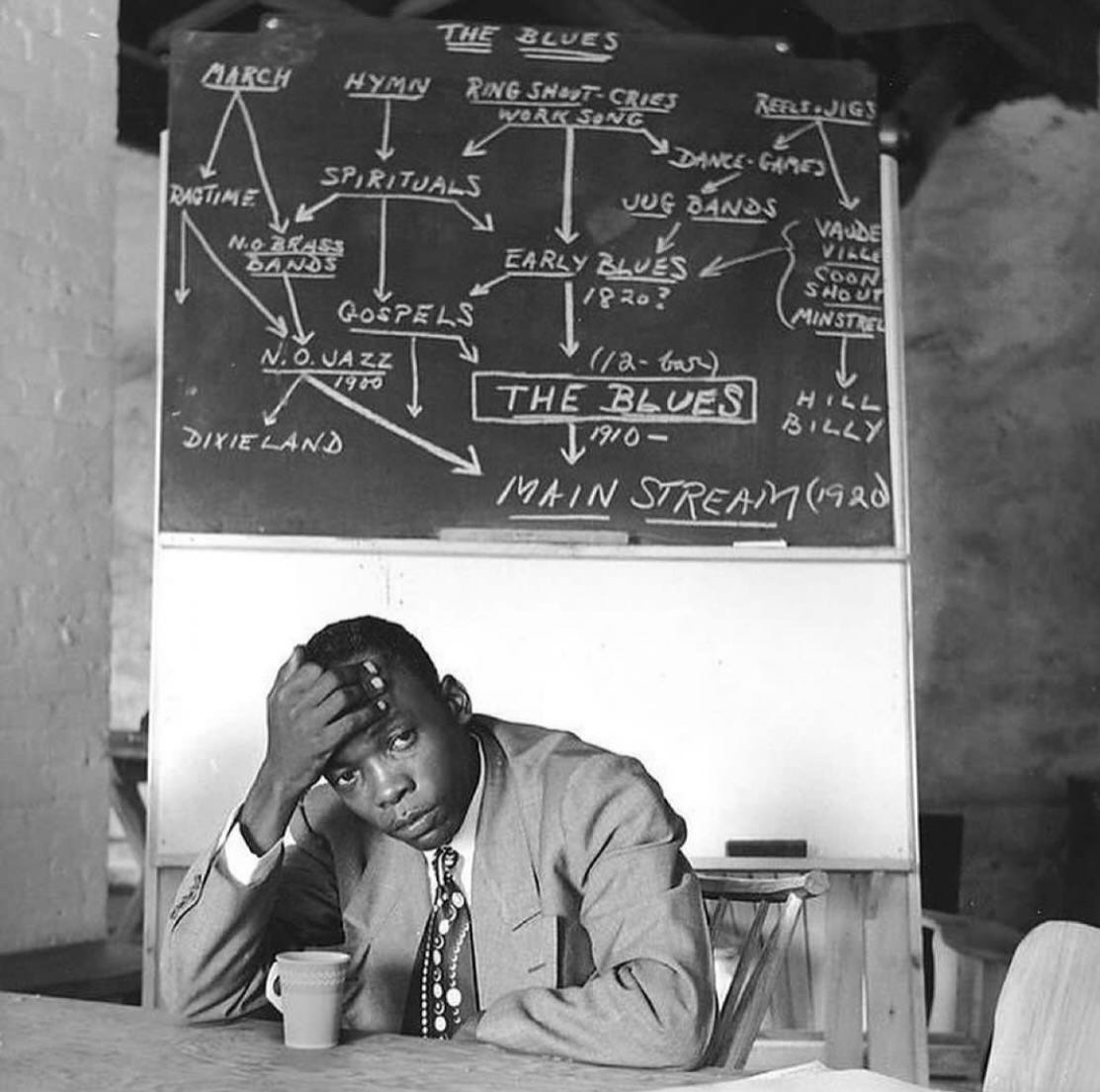

This 1950s-era photo of John Lee Hooker taken by Clemens Kalischer circulates online:

Hooker is at the Lenox Jazz School organized by Martin Willams and Gunther Schuller, and to me it looks like the great bluesman is oppressed by his surroundings.

Shuja Haider noted that this photo foreshadows the facepalm meme where Jean-Luc Picard is once again encountering the troublesome Q:

“Don’t make a hero do a facepalm” is something else to keep in mind as I continue writing about Louis Armstrong and the rest of the jazz greats.

Recently I was doing a shoot for my next Blue Note disc with the excellent photographer Keith Major. We were looking over a few shots in the studio and I said one was “Not bad.”

Keith replied, “Not bad is not good.”

Again, the comments section is open to all for two or three days. Ask me anything! (Doesn’t need to be about the creative process.) If you don’t chime in this time, I will host another open thread at the top of December. Sincere thanks for reading and listening.

The comments are now closed. Thanks for reading!

Just wanted to submit some friendly criticism, for whatever it's worth (probably not much!). The lumping together of all “African” culture is something jazz musicians do a lot and it is a deeply inaccurate practice from both cultural and musical perspectives. It was a specific subset of African music that arrived here in the United States of America which did rely on a steady beat, at least some of their musical genres did, but in other parts of the new world there were African slaves that arrived with very different concepts of musical pulse and time. If it’s of interest, “The World That Made New Orleans” and “Cuba and its Music”, both by the one and only Ned Sublette, dig deep into these matters!

Was reminded of this quote from the new Henry Threadgill book: "..You can't explain art. It simply doesn't work that way. .. I find that the less I say about my music, the better. If I say anything, it tends to be oblique or oracular: words meant to jar the listener out of the complacency of expectation." Somehow still finding Easily Slip Into Another World's 400 pages of Threadgill "not explaining his art" a thrilling page-turner to be sure.

No question really, just another book recommendation.