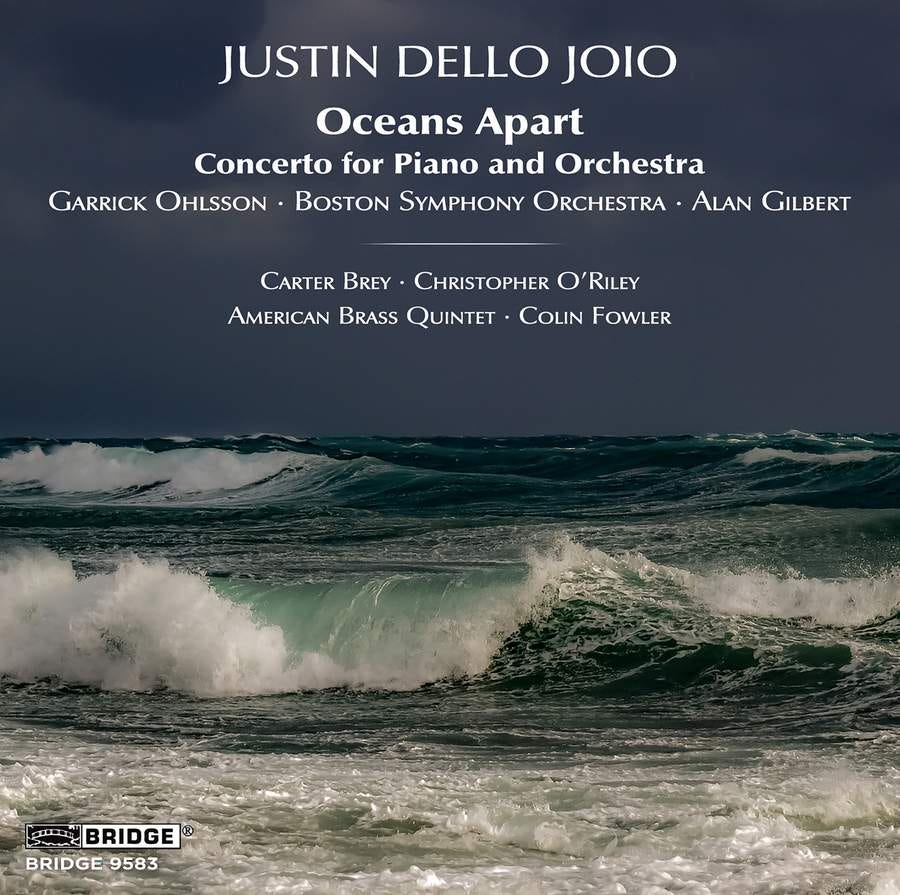

Justin Dello Joio has a dream team of marquee talent for his latest release: Pianists Garrick Ohlsson and Christopher O'Riley; cellist Carter Brey; the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Alan Gilbert; the American Brass Quintet. The excellent organist Colin Fowler might not be quite as familiar a name to the average classical music listener but I know Colin well, for he’s Mark Morris’s music director. (Hi Colin!)

These great musicians surely show up for Dello Joio because Dello Joio is in conversation with music for music’s sake. It all sounds, it’s hard but not too hard, it lays right, the emotions are clear, the harmonies are crystalline, the counterpoint is correct, the influences are the best influences. A lot of classical music written these days aims for something it can never be, but Dello Joio is perched dead center, doing exactly what is supposed to be done.

Oceans Apart is a 19-minute concerto for piano and orchestra; the recording is of the premiere in Boston. Dello Joio says:

Writing this piece conjured to my mind the unlikely images of big wave surfers; one person surrounded—nearly consumed—by the daunting force and fury of these massive 100-foot walls of water. That scale feels akin to the relationship of a piano soloist and the force of a large symphony orchestra, whose sound is a vibration that manifests as a wave.

The opening and closing sounds of the sea are conjured through orchestral special effects a bit in the Lutoslawski manner,

while the piano part is a fearless update of the Romantic tradition. It’s a good thing Garrick Ohlsson is large and in charge.

Ohlsson was 74 at the concerto’s premiere this past January, and deserves true kudos not just for his amazing performance but also for simply showing up in the first place. The famous pianist could be resting on his laurels and only playing superb renditions of Chopin and Beethoven for his devoted fans, but Ohlsson is still in the trenches, passionately promoting complex and technically difficult new music. (Also recommended: Garrick Ohlsson’s previous recording of Justin Dello Joio’s Two Concert Etudes and Piano Sonata.)

The structure of Oceans Apart is very tight, and includes such discernible elements as introduction, allegro, big tune, cadenza, apotheosis, and coda. Dello Joio’s ear is immaculate and the performance could not be better. This is a major new piano concerto.

Due Per Due rattles and sighs like a grumpy demon who has seen better days. Indeed, the first movement, “Elegia - to an Old Musician” is for Dello Joio’s father, the famed composer Norman Dello Joio, an associate of Martha Graham. After a certain amount of moping about, a truly glorious cello melody bursts forth with lush piano harmonies in support. The second movement, “Moto Perpetuo” is more straightforward, a chromatic allegro sent straight down the track, a stellar display piece for eminent virtuosos Carter Brey and Christopher O'Riley.

Blue and Gold Music begins with the Zimbelstern stop on the organ, an ancient toy for tinkling random bells. The work was written for Trinity School’s 300th Anniversary and the title Blue and Gold Music references the school colors. This somewhat unlikely commission would result in a full-throated salute to the “Americana” tradition of formal composition: Aaron Copland, Roy Harris, Samuel Barber, Leonard Bernstein, Morton Gould, Norman Dello Joio, and so forth. Naturally, the members of the American Brass Quintet are given tuneful lines in the “Fanfare for the Common Man” idiom, but that impish sophisticated offspring Justin Dello Joio undoes all that from deep inside a dense contrapuntal web. (Copland could only dream of such sophistication.) I’ve been unable to stop listening to Blue and Gold Music since getting the recording; this music is exactly what I wanted.

Thanks for these—the Blue & Gold piece is great. I had to revisit some Copland to check whether I could agree your dig on his counterpoint was justified, and I get your point, he doesn't really do a lot of dense contrapuntal textures, certainly nowhere near as much as say, Hindemith or Shostakovich, but the fact that he was such a gifted texture-painter says to me that the fact he didn't use that texture more was a stylistic choice rather than any deficiency—It's kind of like dinging Bach's kids for not writing as many fugues as he did, when they were really just doing a different style. Also: the finale to the third symphony has some ripping counterpoint, so he could certainly do it when he wanted to!

(Trivia note: my dad interviewed Copland in 1966, with mic operated by his friend the young Steve Martin!)