My first girlfriend (and eventually, first wife) was the fine mezzo Karen Goldfeder. We would read through a fair amount of easier lieder and song rep together: the Schirmer editions of Italian arias, the Unknown Kurt Weill, and so forth. In an anthology of Western music we discovered “General William Booth Enters Into Heaven.” At first glance, it seems like the opening of Ives’s famous song is a mistake, but it turns out that the notes are actually correct. It is a drum cadence on the piano.

Keith Jarrett told me, “I went through a long Charles Ives phase, and gained a lot from him. The first time hearing him is revelatory, of course.” I had that kind of revelation with “General William Booth Enters Into Heaven.” Somehow I found the LP recording of Marni Nixon and John McCabe: Most people know Marni Nixon from her time as hired gun ghost singer for Audrey Hepburn and other big Hollywood stars, but I know her from “General William Booth Enters Into Heaven.”

I was accustomed to getting away with adequate sight-reading in the sessions with Karen on Italian song and Weill, but “General William Booth” made me practice, bar by bar, note by note. Eventually I could do it, more or less, and I accompanied Karen in that piece when she successfully auditioned for Gregg Smith and the Gregg Smith Singers.

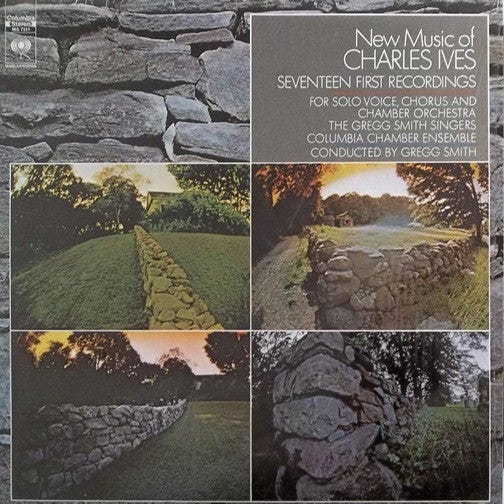

Smith was a colleague of Robert Craft; the Smith Singers were on key Craft recordings of Schoenberg and Stravinsky for Columbia in the 1960s; Smith himself conducted certain Schoenberg and Ives recordings on his own. In many cases these were the premiere recordings of major works by major composers Stravinsky, Schoenberg, and Ives. (Smith told me that one of the best of his recordings from those halcyon days was Schoenberg’s “Friede Auf Erden.”)

Soon after Karen started rehearsing with GSS, someone canceled or got sick, so I got the call to show up at the first rehearsal of Stravinsky’s Mass with Robert Craft conducting. This was probably 1993, when I was 20 years old.

The “Sanctus” movement of the Mass has an exposed slow quintuplet that is a serious rhythmic challenge to the average oboist. In rehearsal with Craft, I somehow kind of nailed that quintuplet the first time, probably a mistake as much as anything. Craft looked over at me and muttered, “Not bad.”

That tiny exchange was an extremely helpful inspiration, almost an injunction to keep learning about classical music.

Back to Charles Ives: Around the same time, during my second year at New York University, I took a jazz composition class with Jim McNeely. Jim played the 1985 Michael Tilson Thomas recording of “From Hanover Square North, at the End of a Tragic Day, the Voices of the People Again Arose.” The class sat in silence, listening to the school speakers as the 10-minute work took its epic journey. As Jarrett says, another revelation. Afterwards I went up the street to Tower Records and bought the CD — maybe the only time I was affected quite this way by a recording cued up by a teacher in a class.

What you hear first shapes the rest of the story. To this day, I don’t think there’s any better Ives than “General William Booth Enters Into Heaven” and “From Hanover Square North, at the End of a Tragic Day, the Voices of the People Again Arose.” Both are seriously dissonant and modernist, but both also offer moments of clear tonal beauty, where the sun comes out and the emotion transforms into “glory for god.” I re-listened the Nixon/McCabe and the Tilson Thomas while working on this post: both still have the power to make me weep.

I dropped out of college after two years, but pretty soon I was the regular pianist for the Gregg Smith Singers. Touring was a madcap adventure that lived on scandal and gossip. Most important was the music itself, of course. Through that job I briefly met many composers, including several that have gone on to be important in later studies such as Hale Smith, Louise Talma, William Duckworth, and Leo Smit. The best piece I played in performance with the GSS was Irving Fine’s The Choral New Yorker, which laid the groundwork for my eventual centennial overview. (Gregg Smith told me that he thought that Irving Fine and Ravel had the best command of harmony, that each chord in their works was a jewel.)

Smith loved all sorts of music, and addition to a steady diet of modern choral composition he would give masterclasses in the Monteverdi Vespers. I asked a lot of questions, and he was always very kind. Smith must have appreciated my enthusiasm for learning, for he suggested I play Hindemith’s serious concerto The Four Temperaments with orchestra at his music festival in Saranac Lake. I refused, thinking (quite rightly) that it was beyond my capabilities.

While I didn’t play the Hindemith at Saranac, I did end up being house pianist for a few GSS cabarets, where the members of the choir would sing solo songs. The singers were impressed that I could play basic jazz for the Great American Songbag (Cole Porter/Gershwin etc.) event, but I learned more from the salon presentation of Ives selected from his massive collection 114 Songs.

The great singer Rosalind Rees (also married to Gregg Smith) was the musical director for the Saranac cabarets. When we went through the list of singer-generated requests from 114 Songs, Roz looked at me and smiled. “Maybe not that one,” pointing to “Housatonic at Stockbridge.” I was relieved, because “Housatonic” was one of the longest and the hardest in the book, even harder than “General William Booth.”

Fortunately, many of the 114 Songs are comparatively easy. Ives was undoubtedly thinking about what in Ives’s era they called a “home pianist.” In my early twenties I was probably about one small step above “home pianist” level.

When Gregg Smith could get an organist and a few extra percussionists, he would program Charles Ives’s Psalm 90. (The common edition used for many years was edited by John Kirkpatrick and Gregg Smith.) For many this is Ives’s greatest choral work, an other-worldly meditation on life, the universe, and everything. One time in Connecticut we were short a percussionist so I stepped in to play the chimes part, marked “As church bells, in distance” in the score. How hard could it be? Actually: pretty hard. While the chimes part is only 3 notes, those notes go in a steady and exposed 5-beat sequence, and don’t have anything to do with the other percussion, the organ, or the chorus.

I got lost at one point and certainly didn’t manage an even, “distant” sonority. Afterward Gregg Smith teased me about how loud some of my “bings” and “bongs” were. He also said the same thing happened to him years ago, when he sat in on chimes for Psalm 90, thinking it would be easy, and didn’t pass muster!

So, I learned to practice a hard score from Ives’s “General William Booth,” and I learned to study up and take a simple ensemble part seriously from Ives’s Psalm 90.

The book 114 Songs also taught me so much. I would leaf through Karen’s copy and wonder how the composer could write in such varied styles. My favorite was “At the River.” (If someone is seeking to tease out the influence of Charles Ives in my own jazz music, I’d suggest starting with “At the River.”)

Not all of Ives is equally successful. Indeed, of the great composers, Ives is one of the most inconsistent. (This is common knowledge: even someone like Gregg Smith, whose career was inextricably intertwined with Ives, wouldn’t argue otherwise.) The Concord Sonata is famous, so I bought the score and heard it live and on record. I liked atonal music (I still do) but I just didn’t respond to this truly bizarre score until 1999 and the release of Ives plays Ives. Much of the CD is only for specialists and historians, but it closes with a flawless take of the relatively accessible slow movement of the Concord Sonata,“The Alcotts.” Previously I thought endlessly quoting the motto of Beethoven 5 was an embarrassing gaffe, but I was wrong. In the composer’s own playing, “The Alcotts” spoke truths to humanity. With this fresh inspiration, I was able to go back to the rest of the Concord and make more sense of it all.

By this time I was ensconced in playing classical music regularly for Mark Morris and the Mark Morris Dance Group. There’s no doubt the only reason I could work with Morris at this level was my previous experience with Gregg Smith, which again, started with Ives and “General William Booth Enters Into Heaven.”

I spent over five fruitful — even life-defining — years with Mark Morris, but then I started to panic that I would never play any jazz gigs if I was safe and secure inside a dance company. After quitting Morris in 2002, I was suddenly in the jazz limelight with The Bad Plus. It was like I written my own script for a movie about me.

There wasn’t too much literal Charles Ives influence in TBP, but the fact that I had spent a decade seriously investigating modernist classical music was surely one reason TBP sounded so different than most other piano trios at that time.

In 2007 The Rest is Noise by Alex Ross was published, and I ended up playing for the book release party and a few gigs on the road during the following years. Since Alex was a classical music critic and I was a jazz pianist, he thought there was not too much conflict of interest, for there would be no occasion to write about me in The New Yorker.

It was an honor to be associated with Ross and his terrific book, but privately I did not feel like I was in an enviable position. Sure, I could play classical music well enough in chamber ensembles, but I wasn’t a finished virtuoso in solo repertoire, and Ross’s audience would be used to hearing the best of the best. (I was certainly proven right: To my horror, Marc-André Hamelin came to the San Francisco performance. Thank god he didn’t say hi before the show, I only knew he was there afterwards.)

To do something a little different, I tried to find pieces that I could learn from a recording made by the composer. The final Rest of Noise tour playlist included Stravinsky, Shostakovich, Bartók, and of course “The Alcotts.” I started with the score, but after the notes were locked in, I just played along with the composer at the piano. I figured that was one way to deal with interpretive issues.

As it turns out, Ives changed a few things in his recording of “The Alcotts.” He nails all the harder and more dissonant passagework, but a few slower and melodic events are strikingly different. I went with the recording, of course, wanting to prove to the world there was a good reason for a jazz pianist to be turned loose amongst standard repertoire!

Truthfully, I figured nobody would notice or care, but then the tour took us to the Gilmore Keyboard Festival, where I met the fabulous composer Curtis Curtis-Smith. After the performance, Curtis-Smith found me, eyes alight. “You play the rhythms in ‘The Alcotts’ more like Ives himself than most,” he said.

Like the quintuplet interaction with Robert Craft, this small moment with Curtis-Smith was a big boost to keep going, to keep practicing, to refresh all the streams in American music.

My most recent public Ives performance was two of the 114 Songs, “The Cage” and “Housatonic at Stockbridge,” with tenor Mark Padmore for his “Songs of the Earth” recital. While preparing the repertoire, I was delighted to finally get my own copy of 114 Songs and look it all over again three decades later. I now call 114 Songs “The Bible” and recommend it to my jazz students at the New England Conservatory.

While Roz and I agreed to set aside “Housatonic at Stockbridge” way back when, now I can play “Housatonic,” and even play it pretty well. My good friend Rob Schwimmer came to hear my first run-through of the program with Padmore before we took it on tour. Afterwards he said to me, “I never heard many Ives songs, but that ‘Housatonic’ piece was amazing!”

A very interesting article. Thank you for it, Ethan.

Hi again Ethan... this is off topic, but I took note of your mention of The Unknown Kurt Weill (and I assume the landmark Nonesuch album by Teresa Stratas.) I was wondering if you’re familiar with the John Lewis/ Michael Zwerin/ Eric Dolphy Orchestra USA recording of Weill theatre tunes in a Third Stream-ish setting. Since my high school days, I’ve found Weill endlessly fascinating. Cheers!