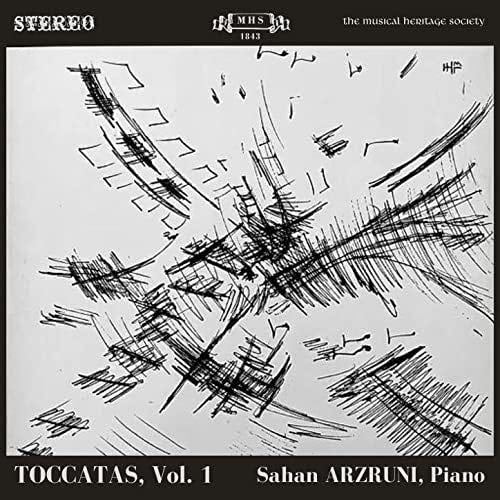

About 20 years ago I looked everywhere in vain for Şahan Arzruni’s 1974 Toccatas LP. Some of it was basic research, for I was practicing Louise Talma’s Alleluia in Form of Toccata and wanted to hear Arzruni’s version. Beyond that, I simply thought the idea of a record dedicated to toccatas was a good one.

While I never found a copy back then, the album is now finally accessible on the streaming services. However, much of the time the metadata is not obvious, a particular problem when all the pieces have the same title, “Toccata.” Taking matters into his own hands, Arzruni has uploaded a fresh digital transfer of the contents to YouTube with his own liner notes and notably glamorous credits: Engineered by Stan Tonkel at Columbia 30th Street Studio.

An older generation remembers Arzruni as Victor Borge’s straight man; Arzruni also has done a tremendous amount for Armenian composers. A budget recording of familiar Chopin from 1994 is a worthy entry in an honored genre. (Arzruni’s comment for the YouTube upload is amusing.)

The Toccatas LP is a virtuoso affair, made up of eight difficult pieces, many of an etudé nature. I have copied and pasted Arzruni’s notes followed by my own casual thoughts.

Şahan Arzruni turned 80 in June; consider this post a belated celebration.

Robert Schumann

SA (Şahan Arzruni): The term Toccata derives from “toccare” meaning “to touch” in Italian. Robert Schumann (1810 - 1856) composed his Toccata when he was twenty-two years old. Perhaps the best-known specimen among all piano toccatas, it displays remarkable maturity and craftsmanship. The work transcends the mere exhibition of pyrotechnics and conveys a rich musical substance. The widely spaced double notes, octaves, and shifting chords constitute a framework within which germinal ideas take shape to form an extended sonata movement.

EI (me): A famous piece. Talented teen pianists eagerly compare recorded versions just to see who can play it the fastest. Listening to Arzruni, I am struck by how this difficult-to-play composition is simply gorgeous music. For the jazz cats: Sullivan Fortner works on the Schumann Toccata.

Franz Liszt

SA: The short Toccata by Franz Liszt (1811 - 1886), unpublished until 1969, is a notable example of the master’s late works. Its harmonic language and quasi-improvisational sound give the music an eerie quality, creating a metaphysical atmosphere. It is a tone imagery, very much like a Debussy Prelude: one views the music as a picture, evolving details gradually from the first impression.

EI: This must be one of the first recordings of what is still today an unfamiliar (but very good) late work from Liszt. Arzruni’s comparison to Debussy is common wisdom when discussing the gnomic or mysterious aspects of late Liszt. In a blindfold test I would guess Ferruccio Busoni, partly because the piece begins in media res C major and drifts off in A minor, which seems like something Busoni (and no 19th-century composer) would do.

Alicia Terzian

SA: Toccata by contemporary Argentine-Armenian composer Alicia Terzian (b 1934) is brilliant – full of fireworks and driving rhythmic patterns. Structurally forthright, the composition is based on two contrasting motives. It’s modal flavor and characteristic open-fifth sound are the unifying elements of the work.

EI: Terzian is turning 90 next year and is an important part of Argentinian musical culture. This early work is influenced by Ginastera. Like the Khachaturian Toccata below, Terzian’s example has the “universal folk rhythm” of 3:3:2. That would perhaps be an interesting research topic: Trained composers writing folklore-based 20th-century concert music exhibiting an obvious 3:3:2.

Josef Rheinberger

SA: Josef Rheinberger (1839 - 1901), born in Liechtenstein, is known primarily for his organ compositions. His unusual Toccata is a synthesis of three elements: baroque counterpoint, classical form, and romantic temperament. The structure is ingenious: the first theme of the main section is derived from the introduction, while the second theme is actually the two parts of the first subject reversed. Superimposed thirds and sixths give a strong flavor of Brahms’s music, while spaciousness and contrapuntal writing is reminiscent of Bach. The sequential development and orderly recapitulation give way to an extended coda. Its cascading thirds and stirring patterns bring the work to a tumultuous close.

EI: I’m intrigued when a composer writes in an “ancient style,” and always buy that kind of thing when I find it in a sheet music shop. Yes, that means I have owned a copy of the truly obscure Rheinberger Toccata for several decades. As Arzruni notes, the piano writing presents itself as thick like Brahms, but the opening is à la Bach. True story: When I interviewed Marc-André Hamelin in his home, I brought along the Rheinberger to see if he would consent to a friendly test of sight-reading. Hamelin wasn’t familiar with this score, but proceeded to read it down quite well. A memorable moment!

Domenico Scarlatti

SA: The present version of the Toccata by Domenico Scarlatti (1685 - 1757) is based on the Coimbra manuscript 58. It’s an example of early Scarlatti, specifically of the Portuguese period. It consists of four movements. The first (K. 85) is full of virtuoso keyboard figurations. The second movement (K. 82) imitates the sound of a string orchestra, recalling the style of Vivaldi. The third movement (K. 78) is an Italian Giga, quicker than the French gigue, with running passages over a harmonic basis. The final Minuet (K. 94) is marvelously refreshing, with its chromatic alterations of certain obvious pitches in the melodic line.

EI: There are around 550 Scarlatti sonatas; the big name pianists played a couple dozen of them. A Google search of “Coimbra manuscript 58” seems to only return results connected to Arzruni, so he might have essentially made this particular grouping of what are often called “sonatas” his personal property under the rubric of “toccata.” At any rate, it is wonderful music.

Aram Khachaturian

SA: Next to Sabre Dance, Aram Khachaturian’s (1903 - 1978) Toccata is arguably his most popular work. The Armenian composer combines various musical traits in this dazzling work. Shifting angular rhythms, bravura instrumental display, flowing melodies, and improvisational structure are employed in a free and rhapsodic manner.

EI: Arzruni plays Khachaturian’s showpiece beautifully. I’m 100% certain Chick Corea worked on the Khachaturian Toccata.

Karl Czerny

SA: Karl Czerny’s (1791 - 1857) Toccata is very much like an étude – an exercise on double note. At times it is powerfully brilliant, reminding the listener of the style of Beethoven, and at other times chromatically surging, recalling one of Chopin. It’s a work requiring strength and stamina.

EI: There is no doubt that Schumann was influenced by Czerny’s example when working on his own Toccata. Unlike the Schumann, the Czerny has not entered the repertoire. Probably music like this is really only for other pianists and those who understand the instrument. Czerny’s composition may seem a bit bland on the surface, but the writing exhibits true pianistic genius and requires a performer of Arzruni’s caliber to stay the course.

Louise Talma

SA: Louise Talma (1906 - 1996), a neo-classicist, calls her work “Alleluia in Form of Toccata.” Following a brief introduction, the main subject states the theme “al-le-lu-ia.” The second subject is more melodic. The combination of the two develops the work into a scintillating virtuoso vehicle. Underlying its irregular rhythmic patterns, the uncompromising and driving pulse gives the composition its unique character.

EI: Arzruni knew Louise Talma personally and was an advocate for her wonderful music; Alleluia in Form of Toccata is a strong closer for this unique recital.

I studied piano with another in the Talma circle, the late Sophia Rosoff. When I produced a 2012 concert of Talma, Miriam Gideon, and Vivian Fine for Sophia, I learned Alleluia in Form of Toccata and played it from memory. My program note from that concert:

After a brief herald of bells, a syncopated perpetual mobile commences its cheerful but tightly-structured course. Talma called it “a tonic to encourage optimism.” Despite a history of success in recitals, this piece unfortunately remains on the fringe of the literature.

At that time a program of women composers was a bit of a novelty. No longer! Indeed, there are at least seven versions of Alleluia in Form of Toccata on YouTube at the moment (including a scrolling-score video by Kaisar Anvar), suggesting that the work is finally on its way to becoming a repertory staple.