Brian Glasser is a UK journalist and the author of In A Silent Way: A Portrait of Joe Zawinul. Every month in Jazzwise magazine, Glasser asks a musician to talk about a record that was a “Turning Point.” (Great idea!)

The 2012 “Turning Point” where Steve Swallow talks about Saxophone Colossus is not online, so I’m reprinting it below. (Swallow and Glasser did not object to my petty theft.)

Doug Watkins died tragically young in a car accident but was very active in the studios and is on many classic records. One of the Watkins disciples is Peter Washington, who sent me Swallow’s “Turning Point” earlier this year. In discussion Peter taught me about how long a note Watkins had, that there was a purr in Watkins’s sound. A good place to hear that wonderful sound is the walking bass solo on “Candy” from the Lee Morgan album of the same name.

By the way: Happy Birthday (August 28) to Peter Washington, one of the true modern greats.

Steve Swallow: Turning Point

As told to Brian Glasser

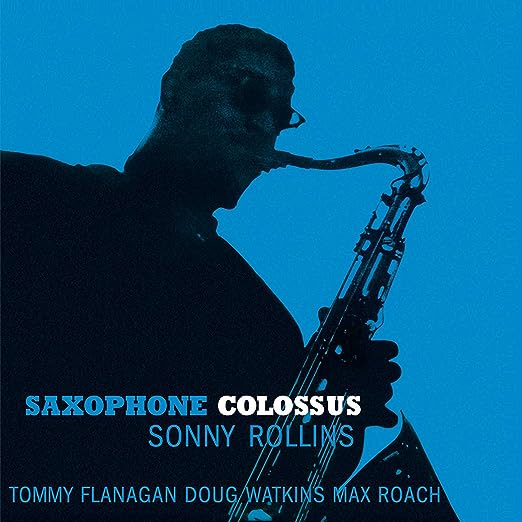

Saxophone Colossus Prestige (rec. 1956) – Sonny Rollins

Personnel: Sonny Rollins – tenor saxophone; Tommy Flanagan – piano; Doug Watkins – bass; Max Roach – drums.

Tracks: St Thomas; You Don’t Know What Love Is; Strode Rode; Mack The Knife; Blue 7.

My record is Saxophone Colossus. In addition to whatever content grabbed you, the choice of record also very much has to do with the season of your life – when you’re at a point that you need something in particular, and when you’re open to influence at the deepest level. The last time I was really grabbed by the neck by some music was when I was in my 50s, when finally the Beethoven late quartets made sense to me. Not so much musical sense as human sense - I heard them as profound. I realised that I’d grown into the ability to be deeply moved by that stuff – either that or Beethoven had gotten better!

Sonny Rollins recorded Saxophone Colossus when I was 16 or 17. I was a fervent buyer of Prestige and Blue Note records at that time and beginning to discover a calling to be a jazz musician. The record had a wonderful confluence of musical skills and personalities that encapsulated everything I needed to know and everything that I loved.

It had these four guys, each of whom had something important to tell me. I didn’t know it was going to be so special to me - I was just buying records as they came out. I knew I liked Sonny Rollins and Prestige, and went to the record store and got five or six albums, brought ‘em home and this one just leapt out at me. What a wonderful afternoon those guys had! Tommy Flanagan’s solos are sublime; Max Roach is at the top of his game, Sonny is just endlessly inventive, for chorus after chorus. As the Gunther Schuller essay points out, his sense of thematic improvisation was so strong, so highly developed. Flanagan’s phrasing was so important. Of course he came out of Bud Powell and the bebop piano tradition; but also I could hear Lester Young there - that kind of pliability in the phrasing to extend over bar lines gracefully. There was a gentle reserve to what he was playing. At some point you decide whether you’re a Lester Young guy or a Coleman Hawkins guy - Tommy’s playing steered me towards Lester.

Doug Watkins is nearly perfect - a greatly undervalued bass player, who died young. He had an enormous unrealized potential that was snuffed out by a car accident. For me, he had the ultimate left hand: he was better able to shape a note than anyone – the attack, the decay, there’s so much you can do with the left hand that’s often not perceived on a conscious level by listeners other than other bass players. Shaping the envelope of a note was something I was made aware of by him and by this record, and it’s a lesson I haven’t exhausted yet.

Doug had come up in Detroit alongside Paul Chambers; and he was somewhat in his shadow because Paul got the higher visibility gigs. They’d gone through the same schools system - this was in the black ghetto - which just by chance had a wonderful music department, with one particular guy who insisted on rigorous study. As a result, they both had scrupulous technique. And even that was a lesson I needed, and heard very strongly on Saxophone Colossus – this was not the jazzman-as-noble-savage myth. As a young middle-class guy, I was susceptible to that myth - it was even part of the attraction of jazz. Listening to Doug, I was deeply aware that his approach to playing this music was studious, disciplined - everything that I was being told to do in the study of Latin literature at school applied equally well to jazz.

I was moved by this recording to search him out in the clubs; and I got to know him a bit - which is also a memory I cherish - to ask him questions, to enlist him as a teacher. That’s how it was done in those days: I learned to play by approaching bass players and asking them questions. I found them all remarkably forthcoming, because it was understood that what we operated on was an apprenticeship system. I asked Doug all kinds of questions about how he positioned his hand and his elbow relative to his hand and so on. He was extremely articulate. I was doing the same thing with Paul Chambers and Percy Heath, Wilbur Ware and my other heroes. All were happy to help – even Mingus, in his gruff way!

So I need to stress again, Doug Watkins meant so much to me. I don’t think I listened to Sonny’s solos until I’d heard that record 20 or 30 times. First things first! Bass players have a focus: they’re learning stuff at a specific level that can be obscure in the ensemble, and having to lean in carefully to hear what the bass is doing. I had a discussion recently with someone about hearing the Coltrane quartet live. He said that he’d had to take Jimmy Garrison on faith because there was no amplification in those days. I completely disagreed – as a bass player, I had some sort of radar that let me isolate every note Jimmy played in vivid detail.

Max is not the easiest drummer to play with – he’s very forthright and didactic and controlling. Doug was much younger than Max, and yet he was able to cajole from Max one of his greatest performances. Especially at mid-tempo - and there’s a lot of mid-tempo on that album. Max is usually at his best at fast tempos; but Doug just nailed him on tracks like “Blue Seven”; and he didn’t do it by bullying – he did it by cajoling. He was kind of the anti-Ray Brown, and I wanted that for me.

So I realise know that my perspective on Saxophone Colossus is a specific one – it’s almost coincidental to me that it’s regarded as one of the best albums of that era!

— Steve Swallow

Peter Washington is the Virgo

People’s (park) Larry Grenadier….

Mark Weiss

From Lytton Plaza, near Stanford (but not of it —- it might be fun to fly them both out here the day of the big game and have them do a cutting contest…