TT 288: Pepper Adams (by Gary Carner)

An excerpt from the forthcoming biography of the great baritone saxophonist

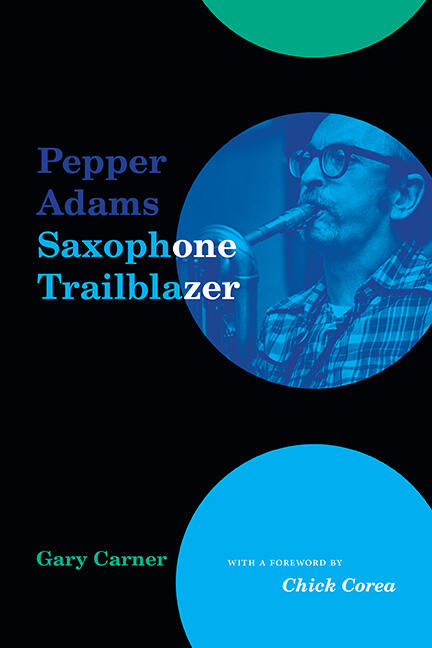

The book Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer, published by Excelsior, will be available in paperback on September 1, 2023 and can be pre-ordered on Amazon. The foreword is by Chick Corea.

Sincere thanks to author Gary Carner for letting me run this substantial excerpt on Transitional Technology. Like all jazz fans I love Pepper Adams and there is so much great information in this excerpt. Looking forward to reading the whole book!

Pepper Adams was part of the crew documented by Mark Stryker in Jazz From Detroit. I reached out to Mark and he sent back a blurb for Carner’s work: “Gary Carner has been stalking the life, music, and legacy of the brilliant baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams (1930-86) with an Ahab-like obsessiveness for 37 years. The great news for the rest of us is that Carner has landed his whale.”

Further info can be found at pepperadams.com,

On a chilly Detroit evening in mid-April 1949, eighteen-year-old Pepper Adams and two Wayne University friends made their way to the Mirror Ballroom to hear alto saxophonist Charlie Parker. Eager to see jazz’s new leader with his working group, all three met at the theater, only a mile from campus. They purchased their tickets, walked upstairs to the balcony, folded their coats, and waited patiently for the show to begin.

The Mirror, above Majestic School for Dance, was well known among Detroit’s jazz community. “I knew of its significance even then,” said drummer Rudy Tucich, who used to ride past it every day on his way to high school. “It was on the second floor. You went in—door on the right side of the building—and walked the stairway up. It was a place of wonderment to me.” Along with the Grande, Beach, Graystone, Jefferson, Vanity, and Monticello, Mirror Ballroom was one of seven majestic dance palaces constructed during Detroit’s early twentieth century Art Deco architectural boom. In 1941, it moved from its historic building on the Near West Side to 2940 Woodward Avenue, on midtown’s central artery, two blocks from the palatial Masonic Temple.

For quite some time that memorable night there was considerable doubt whether Parker would show up. With their star attraction unaccounted for, management convinced trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie—scheduled to appear later that evening at the Paradise Theatre, only six blocks away—to front Parker’s ensemble for the opening set. His surprise appearance, it was thought, would temporarily satisfy the audience while the Mirror’s staff anxiously awaited their headliner.

Eventually, Parker arrived, albeit more than an hour late. After placating the theater’s distressed crew, he exchanged words with his group, assembled his saxophone, and readied himself for the next set. The room was dark except for stage lights directed upon the bandstand. At long last it was finally time for him to count off his first number. “It was a night to remember,” said Oliver Shearer, who, along with Pepper and Bob Cornfoot, watched the electrifying spectacle unfold. “Pepper was ignoring everybody in that whole room but ‘Bird.’ I’ve never seen anyone so excited in my life! He said, ‘Can’t you hear this, man?’ He knew where he was going from that night on, I think.”

Adams had been playing baritone sax for a little over a year. Paying his way through college by working local gigs, he was searching for his own sound and musical conception. But Parker’s transcendent performance that evening gave Adams the paradigm he sought. He decided that his mission was to assimilate the many dazzling attributes of Parker’s style and adapt them to the baritone. Not by copying Parker’s licks and phrases, as so many others would do, but by refining a completely personal approach immersed in Parker’s lexicon. As with Parker before him, his efforts would take a full decade to flower, necessitating thousands of hours of solitary practice and performing with others in a multiplicity of settings.

Adams held Charlie Parker in the highest esteem. “The greatest I ever heard” was how he would assess him in 1984, thirty-five years after seeing Parker at the Mirror. By 1949, Bird’s revolutionary approach was a new way of playing jazz; highly virtuosic and intended for listeners as opposed to dancers. Sometime after his epiphany, Adams and Parker attended a Detroit jam session where each learned that both were classical music aficionados. “Somehow the name Arthur Honegger came up,” remembered Adams about their very first conversation. “I said, ‘Oh, I love Arthur Honegger,’ and immediately I was Bird’s friend because in Europe Bird had heard quite a bit of his music, but he’d never before met an American who’d ever heard of Honegger.”

To attract Parker’s attention as a teenager reveals Adams’s emerging confidence and musicianship. For the next few years Parker would serve as a sage and confidant, in time becoming a trusted colleague. Even with his encouragement, it took a leap of faith for Adams to think that one day he could become a virtuoso jazz soloist on an instrument that, as Stanley Crouch wrote, had “the stand-off qualities and the resistant fury of a stallion that dares you to break him.” In the late forties, most baritone saxophonists still had trouble playing in time with the rest of the band. To complicate matters, with the advent of Parker’s audacious new music, far more harmonic sophistication and instrumental proficiency were expected from jazz soloists. Undaunted and resolute, however, Pepper was convinced that not only was the baritone an instrument he could master, but that no style would be too demanding. Moreover, he was certain that the horn was the ideal vehicle to forge a unique identity and make an enduring contribution to the art form. “I saw it as a wide-open field,” said Adams many years later when recounting his early days as a musician and assessing the big horn’s appeal. “No one was playing jazz in the way that I felt jazz could be played on the baritone. I thought I had a chance to do something entirely different.”

In April 1947, two years before his watershed moment at the Mirror Ballroom, Adams had moved back to Detroit. When he and his parents left in the fall of 1931, America was coping with an unprecedented economic meltdown. Sixteen years later, though, the United States, with its allies, had won a world war. After two decades of deprivation and geopolitical instability, “she sits bestride the world like a Colossus,” wrote historian Robert Payne about America’s postwar dominance. “No other power at any time in the world’s history has possessed so varied or so great an influence on other nations. . . . Half the wealth of the world, more than half of the productivity, nearly two-thirds of the world’s machines are concentrated in American hands.”

No US city was more emblematic of the country’s mid-century financial and industrial might than Detroit. Its position as the country’s economic powerhouse, begun forty years earlier with the inception of the auto industry, had remained intact after the war. Although Detroit’s foundries had been converted into munitions plants during World War II, they had reverted to producing cars and trucks for American consumers soon after Japan’s surrender, and jobs were being created in a wide range of allied industries. For that reason, Detroit attracted the attention of many throughout the country who were seeking employment.

Adams’s mother was no exception. Her return to the city of her son’s birth was primarily due to her new job in suburban Roseville’s school system. Not only was the opportunity for a better life too enticing to pass up, but the move allowed her to reunite with old friends she had not seen since she left. Other circumstances, too, played a part in her decision. In 1943, three years after the death of her first husband, Park Adams, after a lengthy period of decline, she married Harold Hopkins, an employee of Langie Coal Company. They were married only two years before his death in 1945. Burying two spouses within five years, plus the strain of living during the Depression and war years, certainly made a complete change of scenery desirable.

One thing that she could not have anticipated was that Detroit’s extraordinary music culture would in time embrace her only child as one of their own, functioning as a creative laboratory that would catapult him to greatness. Returning to Detroit was the best thing that could have happened to him, Adams recalled in 1984:

Going to Detroit at that time turned out to be a very positive thing as far as I was concerned, as far as developing as a player. I already had some background and could play pretty well. There was certainly a lot of room for improvement. And by moving to Detroit right at that time, I found myself almost immediately within a milieu of fine young players, people pretty much my own age, who were all very eager to play, and get together, and teach one another, and then just hang out together. It was a terrific atmosphere in which to learn music.

Before relocating to Detroit, Adams and his mother stayed all of March 1947 at Hotel Edison in New York City’s theater district. The reason for visiting was to give her son a chance to study with tenor saxophonist Skippy Williams. Four years earlier, Williams took Ben Webster’s place in Duke Ellington’s orchestra, and Pepper first met Williams in Rochester the following year, after attending an Ellington performance.

During his four weeks in New York City, Adams learned about phrasing, how to listen to and blend with other musicians, and how to use dynamics to increase drama. He also learned how to build a set by playing some tunes softer or louder and how to vary tunes from night to night on a gig. Williams’s basic formula was straightforward. First learn the melody and the chords, then analyze the chords and learn to play everything at the proper tempo.

Williams urged his young protégé to evoke different moods on the saxophone. He told Adams that some musicians play with different tone qualities in the upper and lower registers, and to aim instead for consistency: “Some guys take a solo and they play everything loud, and they don’t know when to slow down or make it softer or louder. When you start a solo, you start it and get people’s attention. Sometimes you have to play soft to get people to listen to you and then you bring it up.”

Overall, Williams’s approach to playing jazz encompassed both musicianship and self-awareness. “Those things make you a better musician and a better person,” Williams said. “If you’re a better person you’re going to play better.” With years of accumulated wisdom and indisputable credibility as a musician, Williams gave Adams a master class on the basics of playing jazz while also instilling in him a sense of proportion about other important things in life. Serving a pivotal role as a male mentor at a time when Adams was fatherless, Williams recognized that this special young man was a bit adrift and needed a helping hand. “Pepper was a lonesome person,” said Williams. “There was something he wanted in life, and he lived for that horn.”

Adams was forever grateful for Williams’s mentorship. Although in interviews throughout his life Pepper fostered the conceit that he was a self-taught musician, he was fully aware that the adage is a myth, and in no way should his comments be misconstrued as impertinent. “I consider myself self-taught,” he told his audience at Rochester’s Eastman Theatre in 1978, “but anyone who is self-taught has had an awful lot of help from a bunch of people.” What Adams was really saying about being self-taught is that, as a rugged survivor of the Depression, he was proud of what he was able to accomplish, considering his many constraints, and that he did so mostly on his own terms.

During his first few weeks in Detroit Adams pursued employment and attended as many jam sessions as possible. The previous year he had quit high school halfway through eleventh grade so he could work full-time as a musician. Adams’s first job was at a Dodge automobile plant, followed by a gig assembling auto bodies at Briggs Manufacturing. If Briggs was anything like what Walter Reuther experienced there twenty years earlier, it was back-breaking work with long shifts and a thirty-minute lunch break.

Adams had been very much aware of the Reuther brothers and the social unionist struggle for worker’s rights since childhood. As a socialist and egalitarian who believed that America was intrinsically unjust, Pepper revered the Reuthers’s work to bring about economic justice. Adams “didn’t like the system in this country,” said saxophonist Ron Kolber. He thought it was unfair. I used to call him “the great socialist.” He said, “There’s too many people that don’t have things that they should have in this country, and they can’t get them because of what they are.” He was very adamant about that. . . . I think that deep down in his heart he was a rabid socialist. With those kind of wry witticisms that he had, he always sort of made fun of the system here. He’d always make some kind of remark like, “Oh, yeah, it’s ‘the land of the free and the home of the brave’ if you happen to be free and brave.”

In mid-November 1947 Adams left Briggs for a six-week stint at Grinnell’s, Detroit’s largest music store. After years of listening to classical music recordings and concert broadcasts on the radio, by age seventeen he was so knowledgeable about the repertoire that he was able to function in their record store department as its “classical guy.” While employed throughout the holiday season, Adams worked next to the instrumental repair department. As a saxophonist keenly interested in what was going on there, he became friendly with one of its repairmen. Over lunch one day, Pepper’s coworker told him about a Bundy baritone saxophone, essentially a student-model American-made Selmer, that had come in on trade. “It really plays well,” he told Adams. “You should take it home and try it.” Curious about the instrument, and eager to find a way to become more employable as an underaged musician in a city with competition aplenty, Adams loved the horn. By December he accumulated $125, enough money to buy it, thanks to his employee discount. Just as he hoped, he started getting hired right away.

Adams counterbalanced baritone gigs with a day job on the assembly line at Plymouth’s body plant. It may have been here that Adams participated in a labor strike. Ron Kolber said that Pepper showed him a big scar on the palm of one of his hands, the result of a wound he incurred when he was on a picket line, participating in a strike at one of Detroit’s factories, where he was assaulted by a chain-wielding counterdemonstrator.

That summer Adams first met tenor saxophonist Wardell Gray, initiating an important mentorship that lasted until Gray’s death in 1955. By 1948, Gray had already recorded with Charlie Parker and possessed an international reputation as a jazz player of the first rank. His lyrical melodic lines, magnificent tone, sophisticated use of time, and strong sense of swing had a profound effect on Adams’s emerging style. He and Pepper enjoyed trading horns when they gigged together in Detroit, and other than Sonny Stitt, Adams credited Gray as the finest baritone saxophone soloist he ever heard.

Throughout 1949, Pepper maintained his intense schedule, practicing his instrument, sitting in with various groups, and regularly jamming at Barry Harris’s house at 4721 Russell Street. Apart from his studies and a part-time job at Music Box, a record store, during the first half of the year he had a steady gig with trumpeter Willie Wells and drummer Charles Johnson. By fall there were Monday night jam sessions in the front room of Elvin Jones’s house at 129 Bagley Street in Pontiac, as well as Kenny Burrell’s Wednesday night sessions at Webster Hall.

In 1949 and early 1950 Adams often worked at Club Valley. “That was the best gig in town if you weren’t old enough to work in a bar,” said Pepper. “In Detroit in those days, you had to be twenty-one years old to work in a bar—not just the musicians, but the dishwashers, the night porter—and a lot of us were ready to work well before we were twenty-one,” said Adams. “There was a lot of playing in people’s houses, but there were places to play as well. Because of the fact that people under twenty-one could not get into bars, there were special places for them that didn’t sell whiskey. Actually enough, there was a big audience for this sort of thing.”

In virtually all the ensembles he played with in Detroit, Adams was the only white musician in the band. He was scorned by Detroit’s white players for several reasons. First, they chided his full, commanding sound on an instrument that was more commonly played in a restrained manner and with far less wind. Second, “They objected to my harmonic things,” recalled Adams about his early experimentation with chord substitutions that were unusually dissonant for its time. Third, they criticized his choice of material. “Absolutely no respect for Duke Ellington,” Adams said. “Ask them to play an Ellington tune and they would say, ‘That corny shit?’ ” Fourth, “was drugs, which was part of their social milieu. I was excluded from that automatically.” Consequently, acquiring better-paying gigs was doubly out of reach. Besides ostracization by Detroit’s white musicians, who generally received higher wages from club owners, Pepper was still underage in a town where most of the best-paying gigs took place at clubs where alcohol was served.

Since he purchased his Bundy at Grinnell’s, Adams had been experimenting with mouthpieces to develop a sound on his instrument from which he could be heard without the aid of a microphone or amplification. In autumn, 1949, Wardell Gray returned to Detroit with a Berg Larsen mouthpiece that he was using on his tenor. Adams decided that Wardell’s setup was the perfect solution for getting the kind of “firm and penetrating sound” he sought. He promptly mail-ordered one that would fit his saxophone, eventually having to drive across the border to Windsor, Ontario, to pick it up, because Berg Larsen at that time wasn’t distributed in the United States.

Soon thereafter Adams decided to trade in his Bundy for a new, top-of-the-line Selmer “Super Action” B-flat baritone sax. B-flat horns were considerably lighter in weight than Low-A models and possessed improved intonation across its entire range. Adams bought his new instrument in January 1950 at Ivan C. Kay, Detroit’s Selmer distributor. Because it would oblige him to spend several years paying for it, he brought an expert to the store with him to vet the instrument: Duke Ellington’s baritone saxophonist Harry Carney. Adams had maintained his friendship with Carney and other members of Ellington’s band since he first met them in Rochester in 1944.

By the time he was fully grown in 1950 or so, Adams hardly looked like the prototypical musician who grappled with the big horn. At five feet, ten inches and 155 pounds, with a wiry frame and a narrow chest, he more resembled a bookworm than a jazz musician. His complexion was sallow, his eyes blue, his lips thin. Brown hair closely cropped on each side of his head abutted a thick tuft on top. He wore horn-rimmed glasses beneath his high forehead. Big ears hugged his head, and his front teeth were crooked from insults received while playing ice hockey. Adams projected an owlish mien, with arched eyebrows and a pointed, slightly curved nose that aimed downward above nostrils that flared out in a triangle above a firm, rounded jaw. His face, with its peregrine intensity, belied a very gentle soul. “He was interesting,” said saxophonist Beans Bowles.

Adams was soft-spoken and polite without any hint of aggression. His folksy, northern US accent was an amalgamation of upstate New York and central Indiana dialects that he acquired from his parents, with added flourishes obtained from transplanted southern factory workers and musicians who lived in Detroit. “He reminded me of Coltrane, in a way,” said drummer Arthur Taylor. “He spoke really nice English: ‘Hello, Arthur, how are you?’ Very proper. This guy was great. Coltrane was like that too . . . It has a sweetness about it.”

According to Bowles, Adams “was kind of sheltered. A very studious guy. Very Caucasian.” Nonetheless, his mild-mannered affect and understated appearance wasn’t the look of someone timid or naïve. He was keenly aware of the intricacies of the world, firmly grounded as an individual, and intensely loyal to the music. A resilient child of the Great Depression with a laser-focused mind, Adams had the capacity to envision his future as an artist, the exuberance to design his life ahead of him, and the tenacity to make it happen.

Sometime before the spring 1951 semester, Adams withdrew from Wayne University. He had gotten busier as a musician and was promoted to manager at the Music Box, taking Bob Cornfoot’s place. It’s possible that he felt he was being pulled in too many directions at once, with little time left over for his studies. As part of his decision, it’s likely he considered reapplying to Wayne as a full-time matriculating student to avoid the draft and the possibility of getting ensnared in the Korean War that had begun the previous June.

On July 12, Adams reported to Detroit’s Army Draft Board. “I had a chance for a gig in Sweden and I wanted to take it, but I couldn’t leave the country while my draft status was what it was,” he said. After seeing his name on a list of forthcoming inductees, and aware that volunteering entitled him to request a specific post, “I just went on and volunteered, hoping I’d be turned down on the physical,” said Adams. “Unfortunately, I passed the physical.” Once officially a new enlistee, Adams applied for an assignment with the military band so he could continue to practice his instrument and perform in live shows. With six years of professional experience as a musician, dating back to early 1946 while still in tenth grade, Adams’s request was approved after he passed his audition. A few days later, as a new member of the Sixth Armored Division’s Special Service Section, Adams was ordered to report for six weeks of basic training at Fort Leonard Wood in Waynesville, Missouri, two hours south of St. Louis and Kansas City, in the blazing hot and humid Ozarks.

Throughout his first eighteen months as a soldier, Pepper Adams was stationed at Fort Leonard Wood in Central Missouri. A bustling place, swelling with 100,000 people at any one time, this sprawling 61,000-acre military installation in the Ozark Mountains had once served as both a training facility for American soldiers and a work camp for German and Italian POWs during World War II. A year or so prior to Adams’s arrival, it was chosen as an ideal site to prepare American troops for the Korean War because its scalding, humid summers, subzero winters, and rocky terrain were much like the harsh weather and rugged landscape of East Asia.

From mid-July through the end of October 1951, his initial fourteen weeks in the army, Adams experienced activities at the camp that were completely alien to him, such as firing bazookas, running through obstacle courses, learning how to build airstrips, and being taught how to repair bombed-out pontoon and trestle bridges while under fire. “We all had to go through the same training,” said saxophonist Norb Grey: “Six weeks of infantry training and then eight of combat engineer.”

In mid-August while still in basic training, Adams unexpectedly received an emergency furlough concocted by Charlie Parker. Bird had called the base, posing as the physician of Adams’s mother, so that Pepper could play a gig with him on August 24. Before that time, Pepper had only played with Parker at a few Detroit jam sessions.

“He managed to get me called to a field telephone during Bivouac Week to say he was playing in Kansas City the following weekend,” said Adams. (Bivouac Week is off-base encampment training, during which soldiers learn to improvise temporary shelter.)

It’s near the end of the month and I don’t have any money left. So, he says, “If you can get there, stay with me and I’ll give you the bus fare back to Leonard Wood.” It’s about 180 miles or something. Come the weekend, I hitchhike to Kansas City, arrive around seven on a Friday evening, call up the club, and say, “Is Charlie Parker there?” “No, and the son-of-a-bitch will never work here again!” Clang! [The irate club owner slammed his telephone handset onto its base.] Here I am in Kansas City. $3!

As a backup plan, Adams brought with him the telephone number of a mother of one of his army buddies. With the money he borrowed from her, Pepper got enough to eat, saw the film Roman Holiday, spent two nights at the YMCA, then returned to the base on Sunday. Despite his disappointment about not gigging with Parker nor spending a few days with him, Adams forever remained proud of Bird’s invitation.

Throughout the first half of 1952 Adams stayed on base, practiced relentlessly, and performed with Special Services only when required. Although at heart he was an introvert, who practiced alone in his bunk with a near monomaniacal fervor, when called upon to do so he was also an enthusiastic team player. It’s possible that his practice routine was based on what he learned from Charlie Parker. In his teens, Bird practiced fifteen to sixteen hours a day for three to four years, learning the blues and “I Got Rhythm” in all twelve keys, playing scales in each direction, and mastering “Cherokee” at a super-fast clip. Adams “had all these tunes, just the chord changes,” said Ron Kolber. “They were all in ‘concert.’ He got them from Barry Harris.” As saxophonist Doc Holladay remembered, “Pepper used the service as a school, in a sense”:

He’d pick a tune and he would learn that tune to where he really had it by memory. . . . He’d start playing it in all different keys, so he had that [melody line] in all kinds of keys and be comfortable with it. Then he’d start playing off the changes of the tune, and he’d . . . [do] that until he’d get the changes down to where he could run the changes on the tune. Then he’d start to run that in all the keys. He would digest a tune, just take it apart, make it his own, and then he would go on to the next tune. All the time he was in the service, in the band where I observed him, he was constantly doing that. A new tune every day or two. He could play for hours. The rest of the guys would go out to hang out and party, and Pepper would be in there taking a tune apart.

When Adams practiced chord changes, “He attacked them [with] what scales he could use against the changes, what arpeggios he could use, and then he would try to attack every note in that change from every angle,” said Kolber. After some time doing this, Adams told Kolber, “I don’t even think of changes anymore. When a piano player plays a chord, I know what it is. I can hear all phases of it and I can fit it into what I want to do. I don’t let technique hang me up because I practice all the scales going in all different kinds of directions, going up one scale, coming down another scale, and then doing them in fourths.” He said, “I’ve done this to such an extent that I can attack any change from any direction and go to any direction I want to go.” He was just progressing until it got to a point where he would have so much under his fingers, he could do anything he wanted with it.

On July 11, after completing his first year in the army, Adams received a two-week furlough and went home to Detroit. Sometime between July 13 and 26 he recorded eight tracks for Vitaphone in Ann Arbor, Michigan, led by drummer Hugh Jackson. This was Adams’s first commercial recording in which he could be heard soloing on baritone saxophone. At age twenty-one, Adams was beginning to display some of the hallmarks of his mature style: a unique sound; a consistent swing feel; precise articulation; melodic paraphrasing; tasty, harmonized counter melodies; freedom in articulating the theme; long, flowing lines and beautiful pacing; tremendous drive on up-tempo tunes; and an amazing wealth of ideas. If the session were released in 1953, it would have signaled that a new voice on baritone saxophone had arrived. Unfortunately, the world would have to wait another three years.

Before returning to Missouri, Adams attended a jam session at Elvin Jones’s house, where he first met Elvin’s brother Thad. Initiating one of the most important relationships of his life, one that would in years to come be central to jazz, Pepper realized that his and Thad’s musical approaches were very much alike. “Here’s a cat proceeding on many of the same aesthetic lines that I’ve been doing for a number of years, but in the same way of combining beauty and humor,” Adams told Albert Goldman. “He, too, was playing harmonies that were certainly not common among jazz players.” At the time, said Adams, Charlie Parker “played some very interesting and very complex harmonic substitutions but the Bird-influenced players mostly did not.”

When Pepper Adams returned to Detroit in mid-1953, it was America’s richest city. Its median family income was higher than New York, Chicago, or San Francisco. Because of concessions that the United Auto Workers secured from the automobile industry, Detroit’s factory workers had the best-paying manufacturing jobs in the nation, and its black population was wealthier than anywhere else in the country.

The US was still primarily a manufacturing economy, and that juggernaut was led by Detroit. “If the auto industry had a good year, that meant a good year for the steel industry, for the plate glass industry, for the chemical industry that supplied the paints,” said author Roger Lowenstein. Due to pent-up consumer demand for automobiles after the Second World War, Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors were awash in money, even though labor agreements had compromised some of their profit. GM had record earnings for ten years in a row, thanks to its wildly successful Chevy Bel Air.

Back in his civilian clothes, Adams spent his first few weeks in Detroit getting reacquainted with musicians he hadn’t seen since he enlisted. Most were impressed with how much Adams had improved as a soloist. In recognition of Adams’s newfound prowess, saxophonist Billy Mitchell deputized him as his full-time sub at Blue Bird Inn.

On January 1, 1954, Mitchell went on the road for an extended period, ceding the leadership of Blue Bird’s house band to Beans Richardson, the group’s bassist. Adams replaced Mitchell, joining Richardson, Thad Jones, Tommy Flanagan, and Elvin Jones. The quintet would work together six nights a week until mid-May, when Thad joined Count Basie’s band.

Those 135 magical nights were a peak experience for Adams, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to play Thad Jones’s new small-group music every night with him and two-thirds of his all-time favorite rhythm section. In the previous year Thad had written a provocative book of originals, including “Zec,” “Scratch,” “Let’s,” “Elusive,” “Compulsory,” and “Bitty Ditty,” compositions that Adams considered masterpieces and continued to play and record throughout his career. Thad had originally joined the Blue Bird band in late 1952. At that time, Roland Hanna asserted, only Dizzy Gillespie was Thad’s equal. “Miles would stand under the air conditioner with tears running out of his eyes when he heard Thad play,” said Hanna.

As an aspiring fifteen-year-old saxophonist, Charles McPherson spent a lot of time outside the Blue Bird listening intently to Adams. “I learned a lot,” said McPherson in 2018:

First of all, some articulation things that I could hear slightly Bird doing on records. But records can’t really show you everything. The technology back then isn’t what it is now, and records can show only so much anyway. But I could notice certain things that Bird was doing with his tongue in terms of articulation on the horn. When I heard Pepper in person, right in front of me, I could hear that same approach to articulation that he was doing on the baritone. And, in fact, it seemed like all guys that were playing this kind of so-called “modern music” were using this tonguing and slurring kind of thing on their horns when they played long lines. . . . This impressed me because this takes some virtuosity to bring this off.

As ethnomusicologist Mark Slobin wrote about his hometown of Detroit, “In the first half of the twentieth century, the auto industry produced cars and culture, but in the second half the city manufactured musicians.” Whereas Detroit has good reason to boast about its long history of important musicians of all types, extending well past the Motown hit factory of the 1960s and early ’70s, never before the postwar era or since has this city produced such a concentrated group of world-class musicians, all approximately the same age, who would burst onto the jazz scene at the same time and profoundly influence the music’s history. This tightly knit, unofficial collective of like-minded musicians born around 1930, refined their skills in Detroit’s vibrant 1950’s nightclub and after-hours scene. For almost ten years, from 1947 through 1955, this extraordinary generation consisted of a dizzying roster of now legendary musicians.

One way to gauge the degree to which these Detroiters influenced jazz is to acknowledge the well-known bands that some of them joined once they first left Detroit. Frank Foster joined Count Basie. Paul Chambers was hired by Miles Davis. Curtis Fuller recorded with John Coltrane. Barry Harris played in Max Roach’s quintet. Donald Byrd joined Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. Kenny Burrell joined Oscar Peterson’s group and toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic. Tommy Flanagan worked with J. J. Johnson, Miles Davis, and Sonny Rollins. Elvin Jones toured with Charles Mingus and Bud Powell. Pepper Adams recorded with John Coltrane, then toured with Stan Kenton and Chet Baker. Doug Watkins worked with Blakey and Rollins. Louis Hayes joined Horace Silver’s group.

Philip Levine, who served from 2011–2012 as poet laureate of the United States, was deeply impressed by the Detroit jazz musicians he knew in the late forties and early fifties. “I had no idea that somebody not born with millions could make a life out of art, but I saw these people doing it in the face of all kinds of discouragement,” said Levine.

It gave me a model. You do the work and you don’t whine. You do it for the sake of the work. They played because that was what they were meant to do. All of these guys to me were real eye-openers. I was starting to write poetry, and here are these guys who were about my age . . . and they all knew what they wanted to do already. Not only did they all know what they wanted to do but they were very serious about it. There wasn’t any [romanticized] get up in the middle of the night and write poems shit. It was, “You got to master an instrument, you’ve got to master the classical aspects of the instrument.” I remember Tommy, and Bess [Bonnier], and Barry. You’d sit down and hear them play Chopin. They loved this stuff! Kenny Burrell would play classical guitar. The literature for the instrument they were out to master. All of them. Pepper too. And they were into it with such seriousness. I thought, “Jesus!” They were the greatest thing in the world for me. When I looked at these guys, and women, I saw what real dedication was all about. I would say, at that time Pepper (and Tommy) were just totally into what they were doing. It was, “Out of my way. Nothing is going to derail me. I know what I want to do. I’m gonna be the best goddamn baritone saxophonist in the world.”

How did Adams’s remarkable generation of Detroit jazz musicians come to be? First was the influence of Grinnell’s, a special retailer and piano manufacturer. Second, a great industrial city’s affluence was leveraged to create a first-rate public-school music program. Third, the longstanding custom of informal jazz education was a well-established means of passing the tradition’s vocabulary from Detroit’s professional musicians to those on their way up.

The Grinnell brothers always had big ambitions. At the turn of the century, when they first opened their factory in Holly, Michigan, an hour’s drive northwest of Detroit, they proclaimed it the world’s largest piano facility. Eventually, with more than forty stores in Michigan, Ohio, and Ontario, Grinnell’s became the nation’s largest music supplier and piano distributor. “Grinnell’s had this thing where you could take lessons down at the store on Woodward, but the other thing you could do is buy a piano ‘on time,’ on layaway,” said historian Dan Aldridge. “So, you have all these working-class families in Detroit who had their own piano. It was because of Grinnell’s.” Their business model of supplying pianos to so many Detroit families is one of the main reasons for the city’s dazzling success in producing such an abundance of influential musicians. “The family piano’s role in the music that flowed out of the residential streets of Detroit cannot be overstated,” wrote David Maraniss:

The piano, and its availability to children of the black working class and middle class, is essential to understanding what happened in that time and place, and why it happened. . . . What was special then about pianos and Detroit? First, because of the auto plants and related industries, most Detroiters had steady salaries, and families enjoyed a measure of disposable income they could use to listen to music in clubs and at home. Second, the economic geography of the city meant that the vast majority of residents lived in single-family houses, not high-rise apartments, making it easier to deliver pianos and find room for them. And third, Detroit had the egalitarian advantage of a remarkable piano enterprise, the Grinnell Brothers Music House.

Coinciding with Grinnell’s start-up, Emma A. Thomas, Detroit’s first supervisor of music, established a visionary elementary-school program that emphasized singing. Due to her influence, “public school music programs in Detroit had been recognized among the country’s best by the mid-1920s,” wrote Mark Stryker. “Elementary students had specialist-taught music classes three or four times a week, and it was common in the 1930s and ’40s for students to start playing an instrument in the third grade.”

Ultimately, four high schools—Cass, Miller, Northern, and Northeastern—produced the bulk of Detroit’s greatest jazz musicians. Lucky Thompson, Yusef Lateef, Art Mardigan, Kenny Burrell, Willie Anderson, Lorenzo Lawson, Frank Rosolino, and Milt and Alvin Jackson attended Miller. Situated in Black Bottom on Detroit’s Lower East Side, Louis Cabrera was their band director and the main reason for so much of its success.

Sam Sanders, Barry Harris, Alice Coltrane, Ernie Farrow, and Bennie Maupin attended Northeastern. The school had a glee club, marching band, and instrumental music instruction. “There was a strong emphasis on learning the basics of the language of music,” said Maupin. “I had been in the glee club. Everybody sang. There was no way you could ever go to that school and not sing on some level.”

Charles Boles, Claude Black, Sonny Red, Donald Byrd, Paul Chambers, Doug Watkins, Roland Hanna, Teddy Harris, and Tommy Flanagan attended Northern High. Northern’s jazz program started in ninth grade and was run by Orvis Lawrence, who had played with Glenn Miller and the Dorsey Brothers. “Lawrence [was] a very good Teddy Wilson-type piano player, a very good musician,” said Boles.

Pepper Adams didn’t attend public school in Detroit, but many of his colleagues attended Cass Tech, and the school exerted a strong influence upon Detroit’s musical culture that invariably shaped Adams. Cass functioned as a magnet school for the city’s most gifted young musicians, including Doug Watkins, Paul Chambers, Wardell Gray, Donald Byrd, Bobby Byrne, Hugh Lawson, Ron Carter, J. C. Heard, Bob Pierson, Major Holley, Roland Hanna, Gerald Wilson, Al McKibbon, Howard McGhee, Lucky Thompson, Billy Mitchell, Sam Donahue, Julius Watkins, Dorothy Ashby, and Alice McLeod Coltrane. (Byrd, Watkins, Chambers, Hanna, Thompson, and Coltrane transferred to Cass.) Its music program was as rigorous as graduate-school programs are today. “You got there at something like seven in the morning and you were never through before 9:30 or 10:00 p.m.,” said bassist Charles Burrell. According to Burrell, “You started taking piano, harmony, theory”:

On your respective instrument, all the principals of the Detroit Symphony taught there. You did all your academics on top of that. You started with those, and then you had Orchestra three nights a week and you had Jazz Band two nights a week. . . . In the meantime, you’d listen to the big guys who were playing in joints and things. You’d go out to these joints. A part of your experience was getting to hear them play. You had your mother’s consent.

Cass was a total immersion. “When you finished Cass Tech, you could go out and audition for any symphony in the world,” said Burrell. “You were a finished musician.”

Detroit’s jazz players were extremely charitable when it came to passing the tradition onto younger aspirants. “There were a lot of private lessons going on, and all kinds of opportunities to hear some of these guys and be exposed to their playing,” said saxophonist Bennie Maupin. In 1944, for example, when saxophonist Ted Buckner returned to Detroit from Jimmie Lunceford’s band to lead a small group at Three Sixes, he tutored Yusef Lateef. There were the Jones and McKinney families passing down their musical traditions. “I had good teachers,” asserted Curtis Fuller. “I didn’t have trombone teachers necessarily. I had people like Pepper, and Miles, and Coltrane.” Joe Henderson, Maupin’s tutor, invited his acolyte to work alongside him on local gigs. “Detroit was like that,” said saxophonist Mike Coumoujian. “Even when you are learning, you can get a chance to play with Barry or somebody like that. They would always let you come up and play.”

In 1949, when Frank Foster moved to Detroit from Cincinnati, he taught many young musicians, including Barry Harris, how to work with tritone substitutions. “I think Frank Foster was probably one the best things to happen to Detroit when he came,” said Barry Harris. Before joining the army in 1950, Foster mentored some of Northern High’s budding musicians. “He was becoming a pretty astute arranger,” said pianist Teddy Harris. “He would get Donald Byrd, Sonny Red, and myself and Claude Black, and take us to his house where he would teach us how to read his arrangements.”

Although Foster during that period influenced Detroit’s jazz players, and other musicians, such as Sam Sanders, Teddy Harris, Harold McKinney, and Marcus Belgrave, would later serve as important local mentors, no Detroit jazz musician has had a greater intellectual reach than Barry Harris. As a theorist and sage, Harris influenced his entire generation of musicians, both in and outside of Detroit, as well as many younger and older musicians. “I learned more about improvisation from him than any one person I studied with,” said Yusef Lateef. “We called him the ‘High Priest.’ He’s a brilliant man.”

Beginning in the late 1940s, the workshops that Harris led at his home every week became so widely respected in the jazz world that they drew established touring musicians from around the US, including John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins, who would stop by when they were working in Detroit. Harris’s salon was a place for the exploration of all sorts of ideas. “They discussed literature, politics, philosophy,” Charles McPherson told Richard Scheinin. “I would hear these names batted around: Spinoza, Schopenhauer. I thought, ‘Man, these people are really different.’ ” Harris, a taskmaster who took education seriously, at one point asked McPherson to show him his high school report card. He had a C average and Harris was unimpressed: “Oh, you’re an average kind of guy,” the pianist told McPherson. “It won’t work because this music is complicated and you’re not going to be able to play it if you’re a C kind of guy.” The admonition continued: “You have to read more. You have to broaden everything about your mental capacity. You can’t be in this narrow, skinny bubble here. You have to expand, because when you play this kind of music, the bigger your view is, the better you play. It’s not just notes and chords.”

Detroit’s workshop environment was extremely supportive despite its earnestness. “We would exchange music, we would transcribe music and share it, we would rehearse a lot,” said Kenny Burrell. Adams remembered that time as such a great environment in which to thrive, “because the contemporary kids—I was growing up and playing in kid bands when we were in our teens—were such great musicians. And having so many good musicians in a city like that provides an incentive too. There’s so many highly efficient players that one has to get pretty good on one’s instrument or you have no chance of ever getting a gig. You really got to work at it.”

There was a genuine brotherhood; a sense of being a part of something together that was culturally significant and much larger than themselves. “Every musician I know from Detroit has said this,” remembered drummer Eddie Locke in 1988: “I saw Donald Byrd not too long ago. He said, ‘I never got the same feeling that I got in Detroit.’ There was something else going on there.”

What Byrd and Locke were referring to was Detroit’s non-judgmental approach to teaching the art form, and the profound connection that bound all of them together because of it. “The friendship [shared by Detroit’s jazz musicians gave you] the feeling that you could go ahead and play,” said Locke. “There were so many little, funky joints that had music in it. . . . When you’re in [those] joints you could go ahead and do your thing!” Although young musicians knew better than getting on the bandstand until they had acquired a certain level of technical mastery, playing alongside Detroit’s older musicians was a liberating experience. Coupled with the down-home informality that was found in the city’s many cozy neighborhood venues, it allowed aspiring jazz musicians to take risks in front of an audience. It gave them a chance to develop their identity as soloists without the fear of both embarrassing themselves and of dealing with the suffocating machismo that was customarily meted out by aggressive musicians in other cities. Thus, the hallmark of Detroit’s jazz apprenticeship model was its nurturing way of passing down the tradition. Its jazz musicians became so accomplished in part due to the city’s remarkable, truly anomalous, female-centered educational culture that contrasted so dramatically with the prevailing male-dominated, cut-throat ethos, historically a part of America’s jazz culture since its infancy.

That’s not to say that playing jazz in Detroit was a lighthearted walk in the park. Quite the contrary. “Pepper was a player!” inveighed Locke.

He was serious! There was no bullshit up on that bandstand! That was another thing about Detroit. When you got on that bandstand there was no fucking around! Play! When the cats would play, [they] would tell you [if] you weren’t playing. They would try to show you when you weren’t doing it, not just say it. They’d say, “Come over to my house.” They cared enough about the music to do that. That’s what Pepper was involved with and that’s what made him such a beautiful, beautiful cat.

The immutable bond that connected Detroit’s jazz family lasted well past the time they left town. “A large number of musicians, and people who are friends from Detroit, have continued to be good friends here for thirty years or so,” Adams told Ben Sidran in New York. “I can sit and name forty or fifty people that I’ve maintained friendships with consistently over at least a thirty-year span. I doubt if there are many people in other walks of life that could do that.”

If a Detroit musician needed money, another Detroiter provided it. “I can remember many times when we’ve helped each other out,” said Billy Mitchell. “One just gets the money and walks up to the other and says, ‘Hey, I had a couple of record dates today. Here, you take this.’ ” If someone needed a homie for a gig or recording date, they willingly showed up. When Tommy Flanagan was busy touring the world with Ella Fitzgerald, he was happy to fit into his dense schedule an Eddie Locke recording date in New York. “He didn’t say, ‘How much money you got?’ ” said Locke. “He said, ‘Where? What’s it gonna be, man?’ ” The love and loyalty that Detroiters felt for each other, based upon so many hours of working, eating, and laughing together in Detroit, was in their bones, something they carried with them forever.

On March 6, 1954, a few weeks after Adams began his steady Blue Bird gig, Kenny Burrell formally established the New Music Society. Its dual mission was to produce ongoing Monday-night jam sessions, held at World Stage Theater, and to organize occasional Tuesday-night concerts elsewhere in town. Adams played there every Monday. Because it wasn’t far from Wayne’s campus, many college students would attend, and before long it was packed with excited jazz fans, many of whom were underage and couldn’t get into other clubs. Much like the Blue Bird, the crowd was enthusiastic and respectful. “One hundred fifty people would have been a really large crowd because the place wasn’t big,” recalled Elvin Jones. “It was just as if you were in Carnegie Hall. It was the same kind of reverence, the same sort of atmosphere.”

That July, Wardell Gray returned to play the Blue Bird. Nine years older than Adams, Gray served as one of Pepper’s most important mentors. When they exchanged horns on the bandstand for their own amusement, it gave Adams a chance to hear Gray on baritone, an instrument he rarely played. Other than Sonny Stitt, Gray was the only improviser at that time who played baritone saxophone with precise articulation and a confident time-feel.

On either horn Gray was a magnificent soloist whom Adams greatly admired. “There existed a certain kind of elegance in those long, smooth, swinging phrases,” wrote Mike Baillie. From Gray, Pepper learned “playing in various ways to break up the feelings, having different approaches, different sounds on the instrument, like playing a lyrical phrase with a lyrical sound and then being able to alter your sound to play something else.” Besides emulating Gray’s long lines, gorgeous tone, timbral variations, use of quotations, adroitness with the time, and his unparalleled melodic gift, Adams similarly adopted his use of a Berg Larsen mouthpiece.

Gray’s shocking death on May 26, 1955, when he was found dead by the side of the road outside of Las Vegas after playing Benny Carter’s first set on opening night at brand-new Moulin Rouge hotel, was a personal tragedy for Adams. “The night when he heard about Wardell Gray, if Pepper had known who it was that took Wardell out, Pepper would have [taken] a gun and killed him,” said Doc Holladay. “He was pained, he was angry, and by his own admission, he was violent.” According to Buddy DeFranco, Gray “OD’d and the guys around him panicked, threw him out in the desert.” Bassist Red Callendar, in agreement with DeFranco’s account, blamed dancer Teddy Hale for not acting responsibly: “If the guys he was with had any brains, they would have taken him to a hospital. They could have saved him. Instead, he died and they dumped him in the desert. . . . Had he lived, he would have been one of the truly amazing players of our time. He was anyhow.”

Other than Gray, the only other baritone soloist that Adams admired was Sonny Stitt. Widely respected for his alto and tenor saxophone playing, Stitt also played baritone from 1949–1952 when he co-led a group with tenor saxophonist Gene Ammons. “I heard them several times in person,” said Adams. “Only three years later, Sonny and I worked together, and I tried to get him interested in playing my horn, but he said he didn’t play baritone anymore. He just wouldn’t touch it, wouldn’t even consider it.” Besides his swinging, fluid lines, Stitt’s articulation made a deep impression on Adams and many other players. “Stitt set the pace for articulation on the saxophone,” asserted saxophonist Gerry Niewood. “The clarity of his ideas and his technique [were] just at the highest level.”

Harry Carney, Duke Ellington’s baritone saxophonist for nearly fifty years, of course, served as a model of how the baritone could be played. “He was the baritone player that made me think of filling up the instrument with air, keeping the instrument full at all times,” said Adams. Nonetheless, Carney wasn’t the kind of soloist that Pepper aspired to become. “Carney I always admired, still admire greatly,” Adams explained to Lucinda Chodan in 1986, just weeks before his death.

He was a master of the instrument: The way he could express himself on the instrument, and the range that he was capable of. . . . He had technical facility, everything. He was phenomenal but he was not your jam-session-type player who would go and play “Perdido” for twenty choruses in a club. His solos with Duke: He would compose a solo that would fit where it fell in the arrangement, and to enhance the arrangement around it. He was marvelous at that. He played marvelous solos but he did repeat himself. Every solo on the tune would be pretty much the same because it was geared to fit in the specific spot. So, he was not your basic improviser.

Two other bari players that Adams heard in Detroit though never cited as overt influences were Leo Parker and Tate Houston. Parker played at El Sino and other local clubs in 1947–1948, when Pepper was new to the instrument. “I think he played better than the records tend to indicate,” said Adams. As for Houston, he “was a fine baritone player, a fine soloist,” said Adams. “Tate was not very much into harmonic exploration, but just playing the simple changes and playing with good time, which, in itself, was extraordinary on the baritone.”

Gerry Mulligan and Serge Chaloff, two prominent white baritone saxophonists at the time, held no appeal for Adams. Mulligan played in a Lester Young-influenced, Swing Era-type style, not the intricate Charlie Parker approach that Pepper was busy mastering. As Adams told Bill Rhoden, Mulligan’s “light, airy tone, which was supposed to be hip at the time, I never liked.” Regarding Chaloff, Pepper heard him play in the summer of 1955. “I found [him] extremely disappointing,” Adams told Brian Case. “His lack of swinging, for one thing, and I think that’s largely because he didn’t play the instrument very well, so that he was always technically behind, had to struggle to catch up, and that made his time uneven.” As Pepper told Peter Danson, “I think it’s a common tendency for uninformed people to think of me as a bebop baritone player influenced by Serge Chaloff. But I don’t care for Serge Chaloff at all. That nanny-goat vibrato, the flabby rhythmic approach to playing, turned me off something terrible, particularly contrasted with the way I heard Wardell playing.”

In the summer of 1954, Adams felt it was time to test whether he could land his first record date. Elvin Jones had recorded three quartet tracks for bari and rhythm section, and by September, Pepper had an acetate pressing that he could bring with him to New York. Taking a few days off, he headed east to play the recording for Bob Weinstock, owner of Prestige Records, and Alfred Lion, who ran Blue Note. It’s likely that Adams secured the meetings thanks to Miles Davis’s recommendation. Davis had recorded for both labels, and only a few weeks before, during his six-week run as guest soloist, had worked with Pepper at the Blue Bird.

Nothing in the short run arose from Pepper’s meeting with Weinstock, though it initiated a relationship that led to various dates he would do for Prestige beginning in 1957. Similarly, beginning in 1957, Adams would participate in his first of many dates for Blue Note. Interestingly, although Pepper was always treated by Blue Note as a sideman, from 1957 until the company was sold in the early seventies, he would become the only white musician who would consistently record for the label during its golden era.

While in New York City, Adams sat in at Birdland with Miles Davis, playing Sonny Rollins’s tenor saxophone. Pepper’s appearance, dress, and affect once again fooled someone into thinking that he was not what he at first glance appeared to be. “When I was working with Miles Davis at the Birdland nightclub in New York, Pepper came by,” said Rollins.

He was going to sit in with the band. I thought, “Oh, gee, this guy is probably some guy that can’t play.” Miles knew him, I didn’t. Miles likes to be the instigator of a lot of things, so he said, “Oh, let him play.” Miles knew that Pepper would sound good and would surprise me, and, so, he did. I mean when he played it was really great! It completely flabbergasted me! He played with all the requisites of that time: energy, ideas, drive, and swing; everything! And Miles was looking over there like he told a joke on somebody.

Alto saxophonist Phil Woods recounted a similar incident that took place at a Paris restaurant about fifteen years later when he, Adams, and Swiss drummer Daniel Humair had dinner. This was one of Pepper’s earliest visits to Europe, so very few musicians there knew him. “Humair is quite conversant in the arts, and on wines, and on food,” said Woods.

Pepper was over there on tour, just happened to be passing through. . . . Daniel was kind of making fun of Pepper, figuring this cat was a rube, and didn’t know anything about French culture and all that. Pepper kind of took it and then proceeded to do a diatribe on Daniel. He discussed art to its fullest, proceeded to order an eight-course meal in . . . French, checked the wine list, knew exactly what the good wine was. Daniel felt like disappearing. He had no idea that Pepper was so hip.

According to Ron Ley, “Pepper may well have encouraged Humair’s misimpression so as to set him up for the take-out humiliation that Humair finally suffered.” Although Adams’s soft-spoken politeness and unassuming looks fooled some into thinking that he was an unsophisticated bank clerk or the like—certainly not a hip jazz musician—“meek is not a word that applies to Pepper,” said Ley. “The ferocity of his playing gets closer to the strength and emotion that underlay his personality.”

From at least the beginning of 1955 until early January 1956, Adams was a weekend fixture at West End Hotel’s early morning jam sessions. What I loved most about Pepper “was his sound,” said Bennie Maupin. “He had this beautiful sound and he had already some great ideas. There was continuity to his playing. There was something about it. Every time I heard him I really liked it. . . . He inspired me, just listening to his ideas and his command of the instrument. It was just great to hear what he could do! It gave me perspective. He had an influence on me and I certainly loved what he did.” Gerry Niewood felt similarly about Adams’s playing. “Something that really turned me on was the continuity, from the time he started to play ’til the end of the solo”:

There was a real continuity, one continuous invention, that was tied together. It wasn’t little, short phrases, or little ideas that were not connected or kind of peppered the landscape. I think of him more as a person who would tell a story. Maybe start with an idea, and then explore that idea in many different ways over the time and through the harmony. He would let his mind explore that idea and let it unfold through the solo. The state of his craftsmanship got higher and higher and higher as it went. It’s difficult to do. What separates the best players from the not-so-great players is their ability to connect it all and have that logic. That gets back to his intellect. His intellect was at such a high level that he could really be so inventive with his thought.

At 515 South West End Avenue in Delray, a Hungarian industrial neighborhood downriver from Detroit, the Friday and Saturday late-night get-togethers gave Detroiters an opportunity to work with each other and play opposite visiting out-of-towners. No matter how illustrious a jazz musician might be, he had better be at the top of his game when he came through Detroit, warned bassist Major Holley. “They were in for a rough time. Detroit musicians were like hyenas, vultures, buzzards, sitting around, waiting for these guys to come in and devour them!”

Gerry Mulligan was one of many touring musicians who got manhandled at West End. “Pepper really cut him!” said Mike Nader.

There was a lot of excitement in the air. Gerry Mulligan’s there. Pepper is playing his horn. Pepper’s going to cut him. Everybody was rooting for Pepper. It was almost as good as an athletic event. It was a contest. Two titans on that huge instrument. . . . Pepper outshone him. It was nothing overtly hostile. Pep outplayed him. Pep was really, really on! He was in top form. [Mulligan] was, I think, at times bemused because of the stridently partisan attitude we were displaying towards Pepper. It was very exciting for those of us that were there, and we were all rooting for the hometown guy.

This event may have occurred on the same night that Mulligan and trumpeter Chet Baker descended on Klein’s Show Bar. “Him and Chet Baker came in on us one night and he demolished the guy!” said Curtis Fuller about Adams versus Mulligan. “We went from Klein’s to the West End. He totally embarrassed him and made him look like a kid with that saxophone.”

Just after Christmas, about seven months earlier, Pepper had left his yearlong Blue Bird gig to work with Kenny Burrell, Tommy Flanagan, and Elvin Jones at Klein’s Show Bar. “That was a wailin’ little band,” said Adams. At 8540 Twelfth Street (now Rosa Parks Boulevard) at the corner of Pingree, it was “a very unique place,” said Curtis Fuller. “If you bought a mug of beer, you got free corned beef sandwiches. The kids loved it. They could play chess.” Like the Blue Bird and World Stage, the audience mostly consisted of respectful jazz listeners who came to hear the music and quickly silenced those in the audience who transgressed.

Around May 1955, drummer Hindal Butts assumed leadership of the band, Adams became music director, and Pepper brought in Curtis Fuller, forming the group they called “Bone and Bari.” During the day, Adams and Fuller would often practice together at Pepper’s house. “He heard a little something in my playing that he wanted to cultivate,” said Fuller. “Race relations being what they were then, he had to pick the times that I could come out to his house because the neighborhood he lived in was all white.” To drive Fuller from his place to Adams’s house at 19637 Ryan Road, close to Eight Mile and less than a mile away, he’d put Fuller in the trunk of his car, drive to the back of Pepper’s house, then the two would slink in so that Fuller wasn’t seen by his neighbors. “He liked to run over a lot of Thad Jones, teach me a lot of things,” said Fuller. “Anything that Thad wrote. He just loved Thad!”

One of Adams’s littlest known influences is his mentorship of Fuller, and how, by doing so, he influenced the lineage of jazz trombone playing. “Coming up with Pepper on the Detroit scene, he inspired me, taught me to reach, [to] try to get more out of the trombone without the slide,” said Fuller.

Pepper inspired me with his selection of material to play on trombone, and he wouldn’t release me. He was determined to make me play it by playing it over and over again. Of course, that took me in another direction. I sort of released the path of J. J. Johnson, who was a master, and found a direction where I started listening to saxophonists. That’s due to Pepper Adams. I used that to take me down a path that would lead me to a better place on that instrument. . . . At that time, it wasn’t being done on trombone. He kept telling me the advantage, that no one else is playing like this: “You have the ability. . . .” I can actually say that [Pepper is] responsible for a lot of things I’m playing.

As he reiterated with Mark Stryker, “Playing with Pepper was pivotal. I can’t impress upon you how much I respected and admired him. If I hadn’t met Pepper, it never would have happened for me.” Thanks to his tutelage, Fuller would refuse to accept the limitations of his instrument, just as Adams had done with the baritone. In the next decade, Fuller would record with many of the major musicians of the period and become one of jazz history’s greatest trombonists.

As impressive as the 1950s Detroit jazz scene seemed to bassist Bill Crow, he was left with the impression that Detroit’s musicians weren’t making any money. That might very well be true, particularly for Adams. In 1955 he still lived at home and worked a day job at Al’s Record Mart. Moreover, Detroit had no recording industry of its own and its illustrious radio orchestras were long gone.

The allure of joining a major group based in New York, or, better still, being in such a band and freelancing in New York City—with its exciting recording and studio scene, and the opportunity to earn a living and play on any given day with countless extraordinary musicians—was too enticing to keep these great Detroit musicians in town much longer. New York’s magnetic draw, of course, wasn’t a new phenomenon. The Big Apple had served as America’s musical hub since the 1920s, when “centralization of recording and radio studios, booking agencies, and publishing companies had,” in the words of journalist Otis Ferguson, “turned New York into a ‘microphone to the nation,’ making it necessary for promising musicians around the country to migrate there if they were to parlay their talents into lasting professional success.”

Many of Adams’s colleagues left Detroit within just a few months of each other. “It was looking for broader horizons,” Pepper told Ted O’Reilly. “Some, like Elvin, got a gig on the road and then just decided to stay in New York. Some others of us, like Tommy Flanagan, and Kenny Burrell, and I, all moved to New York at the same time. That was really in search of professional advancement, which I think in the long run has been good.” And so, just after New Year’s Day, 1956, with his life so full of promise, twenty-five-year-old Pepper Adams packed his belongings and moved to New York.

By Gary Carner, excerpted from forthcoming Pepper Adams: Saxophone Trailblazer.