Just this past month I settled in to look at John Le Carré’s first four books.

Call for the Dead (1961)

A Murder of Quality (1962)

The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1963)

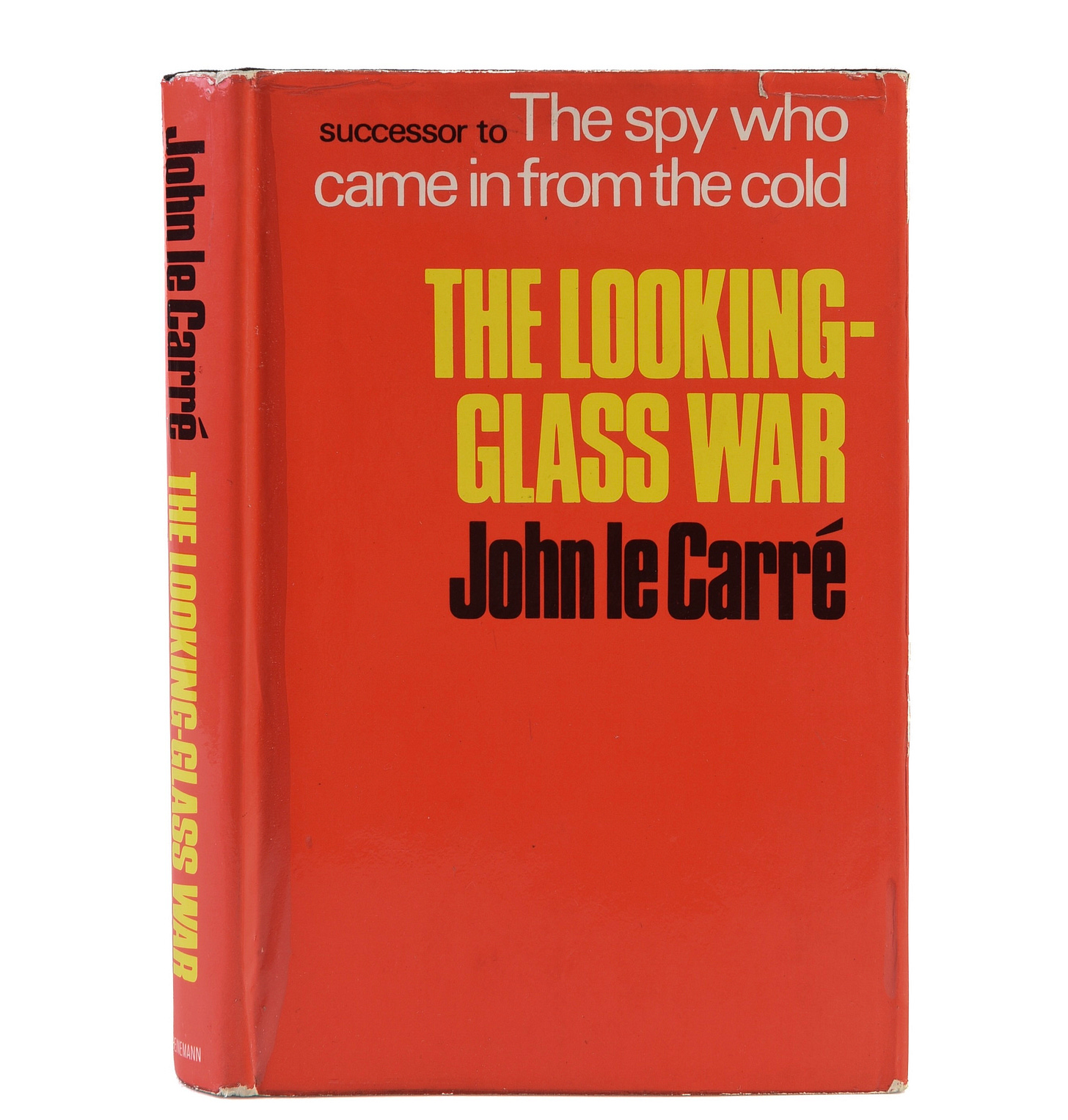

The Looking Glass War (1965)

All four early novels are reasonably short, at least compared to the doorstops Le Carré produced later. They also offer an interesting example of an author finding his way. Both Call for the Dead and A Murder of Quality are murder mysteries. Yes, George Smiley worked as a spy during the war, and there is a certain amount of espionage in Call for the Dead, but the title itself refers to a clue for Smiley’s murder investigation. Essentially Smiley is cast in the role of a Great Detective like Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot or Jane Marple. As with Poirot and Marple — and unlike most literary spies — Smiley is dumpy and un-athletic, a brilliant mind with limited obvious charisma.

Le Carré was still a young man, not yet 30, but the first two mysteries are quite old-fashioned and stuffy, laboriously winding their way to complicated puzzle solutions. Most impressive is the general high quality of the prose: Many sentences offer euphony and insight.

Smiley moves offstage for The Spy Who Came in From the Cold and The Looking Glass War. Rather than being a detective or even the central hero, Smiley is now a bit player, part of the espionage agency called the Circus, working under the devious Control. This was a masterstroke by Le Carré. Motivation moves into the shadows, but the plot reversals are rendered in shocking clarity. Le Carré invented a genre at this moment, a fabulous alternative to Ian Fleming’s flamboyant and jingoistic James Bond. Almost all spy stories conceived after 1965 owe a debt to John Le Carré.

If the first two books seem old-fashioned, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold still feels ultramodern. The novel was a huge bestseller, set up le Carré for life, and remains a template. The plot is perfect and nothing slows down the author’s momentum.

However, true fans of the genre might consider The Looking Glass War as part two of this spectacular genesis, although it flopped at the time of publication, and some of the current online discourse calls it a satire.

The Looking Glass War belongs in that unusual group of texts where an author was inspired by a big success to turn against themselves and their audience. Le Carré himself said he wrote the book as a rebuttal to those who thought The Spy Who Came in From the Cold a heroic tale.

Other examples of this author self-immolation include Charles Willeford’s unpublished Grimhaven and Thomas Harris’s Hannibal (extensive discussion of the Harris canon here). Unlike Grimhaven or Hannibal, The Looking Glass War works pretty well, although there is perhaps too much investigation of motivation. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold is marvelously hard-boiled, with many human emotions expressed as an afterthought. When we are shown the inner-workings of these sad characters in The Looking Glass War, we lose some of the previous book’s focus.

The next time George Smiley appears in print, it will be with Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, the first of le Carré’s famous Karla trilogy. At that point (and for the remainder of the le Carré canon) Smiley is cast as a Great Spy, somewhat the way he was cast as a Great Detective in the first two books. But there’s truly something to be said for his partially off-stage role in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold and The Looking Glass War, where Smiley is a superb technician of uncertain morality, someone to be feared as much as admired.