TT 200: Get Carter by Mike Hodges, Ted Lewis, and Michael Caine

Michael Hodges passed away earlier this week. Minor spoilers for his 1970 directorial debut, Get Carter, are included below.

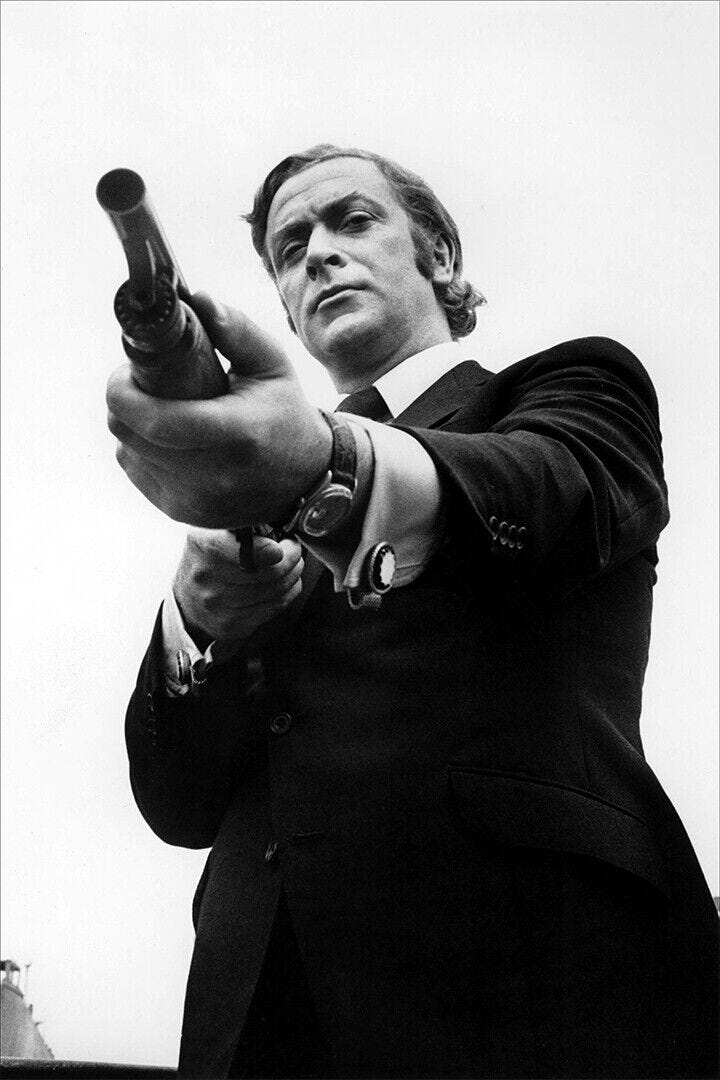

In the very early 1990s, I bought a cool-looking tough guy postcard in the East Village that simply said, “Michael Caine” on the back. There was no other credit for the image:

At the end of the decade I was on tour of England with Mark Morris. A bookstore in Manchester displayed the exact same photo, hanging as a large poster. I asked the shopkeep what the image was from. “Get Carter,” he replied.

Was that a movie?

“Yeah. Michael Caine gangster movie. Get Carter.” The shopkeep hesitated. “It’s set up north, in Newcastle. Americans can’t understand the dialect.”

Fair warning. When I got home I went over to Mrs. Hudson’s Video Library in the West Village, where they rented me a VHS of Get Carter. As the shopkeep predicted, the Northern accent was so strong that I could barely understand a word on first viewing, a problem only exacerbated by a lot of slang I wouldn’t have known to begin with. To make matters worse, the film employs naturalistic editing that can make the dialogue hard to hear.

However, the lack of verbal clarity was part of the movie’s dark spell. I kept watching Get Carter over and over.

Most tough-guy or gangster films like to think they push the envelope or are edgy. To this day I think nothing in this idiom has shocked me as much as Get Carter, at least in terms of violence and casual sex in a bleak and quotidian context.

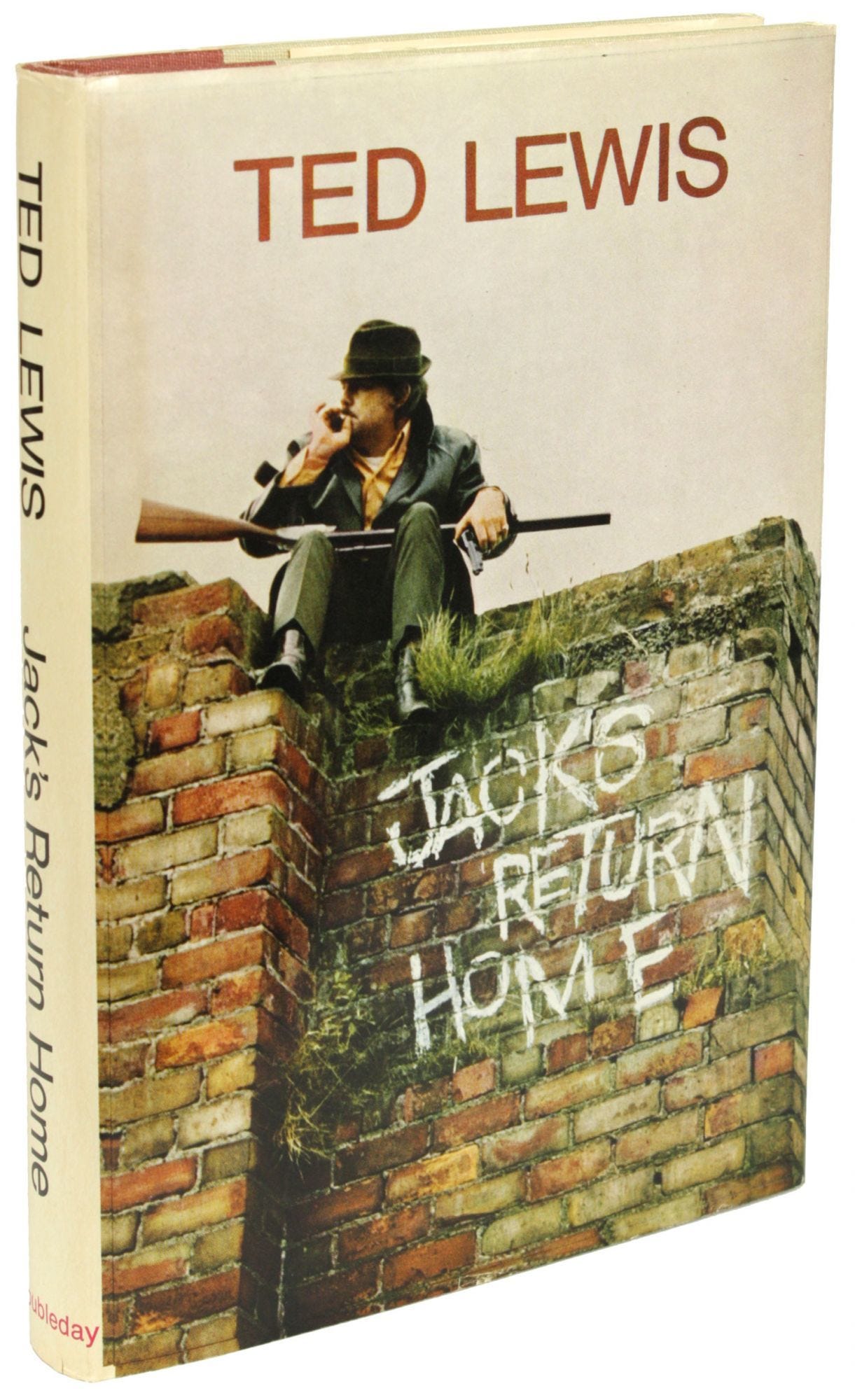

The story is adapted faithfully from a novel by Ted Lewis, Jack’s Return Home. Lewis’s particular kind of grittiness has a true working-class environment. He writes about well-to-do London gangsters with envy in his eyes.

In the press photo above, a man holding a shotgun is dressed to the nines, but to some extent that misrepresents the movie as a classy kind of affair. (Indeed, that particular still is not in the movie proper.) The cover of the first edition also sports a man holding a shotgun, but decaying bricks defaced by graffiti take up more room, surely an appropriate design for the story.

Jack Carter was from Newcastle but he hates it there. Contempt radiates off him in waves, especially when played by Michael Caine. He’s returned from his fancy life in London to avenge his brother’s murder, but he’s also simply proving that he’s better than everybody. The posh peacock flies back to the nest, where he wanders around lowly pubs, bingo games, and the disgusting colliery at the beach dumping slag into the sea, all the while killing as he sees fit, using the women, and getting associates beaten up, arrested, or worse. By the final credits, Jack’s homecoming has proved to be an unhappy occasion for all involved.

Some actors just light up the screen. Michael Caine was an uncredited co-producer for Get Carter, apparently he liked the book and was an advocate for the movie. After a string of successful star turns where he played war heroes or humorous/lovable rogues, Caine wanted to do something truly tough and unethical. He succeeded.

There was a certain moment in the history of crime film from about 1967 to 1975 where directors made all sorts of arty decisions. The audience was forced to follow a confusing plot carefully. Experimental editing was even more abundant than in ‘40s film noir. At the end, the movies slip out of gear and drift to a confused stop, like a car driving aimlessly off the road after the driver has been shot.

Point Blank (1967)

Bullitt (1968)

The French Connection (1971)

The Long Goodbye (1973)

The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973)

Chinatown (1974)

Night Moves (1975)

Even something as mainstream as Dirty Harry (1971) has arty decisions from director Don Siegel including a downbeat ending: When Harry Callahan hurls away his badge into the water after the final showdown, it really feels like he’s absolutely done being a cop. (Even more than usual, all those sequels were a mistake.)

This genre and era speaks to me. Perhaps this mixture of smart and base riffing over a familiar tune comfortably aligns with jazz.

Get Carter was the first British film that I’d seen that had that sensibility. While I can’t call myself a serious movie buff, I know this particular genre well enough that I can use it a prism to learn a bit about overall culture. Get Carter has taught me a little something about England. Le Cercle Rouge (1970) has taught me a little something about France. Although from more recent eras, Sonatine (1993) and Drug War (2012) have that authentic “arty downbeat crime movie” sensibility and have taught me a little something about Japan and China.

For my own taste, a two-hour movie is about the right length to stay close to an anti-hero. While many love the extended journeys of Tony Soprano and Walter White, at some point I resent being asked for so much concern and sympathy as these frankly dastardly souls ascend through their convoluted character arcs.

Michael Caine’s Jack Carter is self-serving and evil, especially towards women (who usually get a kind of gentleman’s pass in this sort of fictional context). A few things occur in Get Carter that are simply beyond redemption.

Jack gets his revenge at the end. It’s “good” that he gets his revenge, we are with Jack — but we also aren’t upset when a bullet unexpectedly goes through his forehead a moment later. The posh rabid dog has been put down, and that’s almost a relief.

(In the remake starring Sylvester Stallone, Jack Carter reforms and lives to fight another day, which is about all you need to know about the state of American crime movies thirty years later.)

Ted Lewis writes Jack in the first person for Jack’s Return Home, but, just like the movie, Jack bleeds out at the end (while somehow still writing the final sentences of a full-size crime novel). Lewis was up against it when his breakthrough book was successfully filmed; probably the author was almost forced to resurrect his famous character for the prequels Jack Carter’s Law and Jack Carter and the Mafia Pigeon. Fortunately Lewis kept Carter vicious and amoral throughout all three books. (Jack Carter’s Law uses the physical characteristics of Michael Caine, George Sewell and Tony Beckley when describing Jack Carter, Con McCarthy, and Peter the Dutchman.)

In the internet era, one can get the essential Lewis oeuvre on Kindle. (Twenty years ago I had to haunt used book stores in London to find these hard-boiled diamonds.) Some think GBH is his best, but in the end I still give highest marks to the first, Jack’s Return Home. The stench of industrial poverty is real.

It’s a great book, but the movie is even better.

Two particularly sensational scenes are not in the book. Presumably they were created by Mike Hodges, who wrote the screenplay as well as directed.

When he first lands in Newcastle, Carter orders a pint in a pub. As the barman starts filling a mug, Carter angrily snaps his fingers and corrects the server, “In a thin glass!” Locals look and then quickly look away. Caine’s facial expression is fierce as he establishes big-town dominance over his former community.

One of the key works of post-war Britain is the play Look Back in Anger by John Osborne. In Get Carter, Osborne plays suave heavy Cyril Kinnear, who is not quite Carter’s boss, but the major associate of Carter’s bosses back in London. Great performance by Osborne, especially during a card game. When Carter bursts through Kinnear’s security to penetrate the card game, Kinnear says, “See what it’s like these days, Jack? You can’t get the material.”

It’s a beautiful line, made all the more beautiful by the blocking: Osborne does not look at Caine or get any visual cues as to the nature of an intrusion.

In the pub, Carter visibly cows the locals; at the card game, Kinnear establishes a more casual kind of dominance through omniscience.

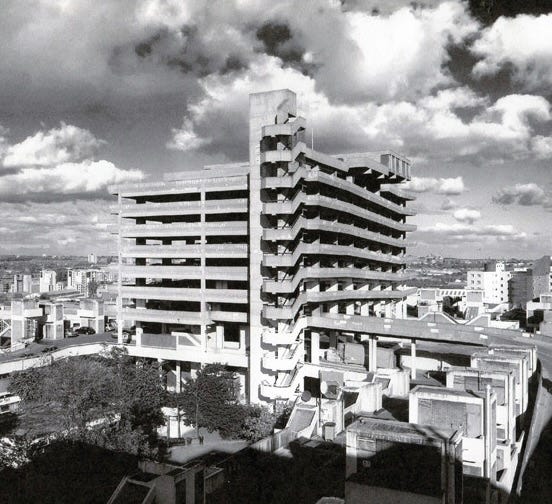

On a later UK tour with the Bad Plus, we played Gateshead, next door to Newcastle, and after sound check I went in search of a famous Get Carter location, the Trinity Square car park designed in Brutalist fashion by Owen Luder. Is it appropriate to feel grief when a car park is demolished? If so, yes, I am sad that the Trinity Square car park was blown up and replaced by something safer and more shopper-friendly a few years after my visit.

The whole film exudes this particular kind of car park flavor. There are thousands of books and movies that follow a similar general revenge plot with a related complement of thieves and murderers, but Get Carter remains in a “Brutalist" class of one.

Footnotes:

1) Roy Budd’s jazzy score is just perfect for the opening scene as the train heads north from London through the tunnel. A few years later, Budd created the theme for another personal touchstone, The Sandbaggers (where I don’t like the music nearly as much).

2) Bernard Hepton is a minor ineffectual villain in Get Carter, but you might know him better as Toby Esterhase in the BBC adaption of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. Tony Beckley is perfectly nasty as Peter the Dutchman, but any serious Doctor Who fan my age grew up with his star turn as megalomaniacal millionaire Harrison Chase in “The Seeds of Doom.”