Kerry James Marshall, TWELFTH NIGHT, and Gary Graffman

("I Really Should Be Practicing")

Sarah and I spent the holiday week in London, where we took in many wonderful things, including two absolutely extraordinary art and theater events.

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories at the Royal Academy offers a well-curated overview of an important American painter active since the late 1970s. The galleries tell a gripping story, grouping the work within genre and period.

The Academy

Invisible Man

The Painting of Modern Life

Middle Passage

Pantheon

Vignettes

Souvenirs

The Painting of Modern Life II

Africa Revisited

Wake/Gulf Stream

Red Black Green

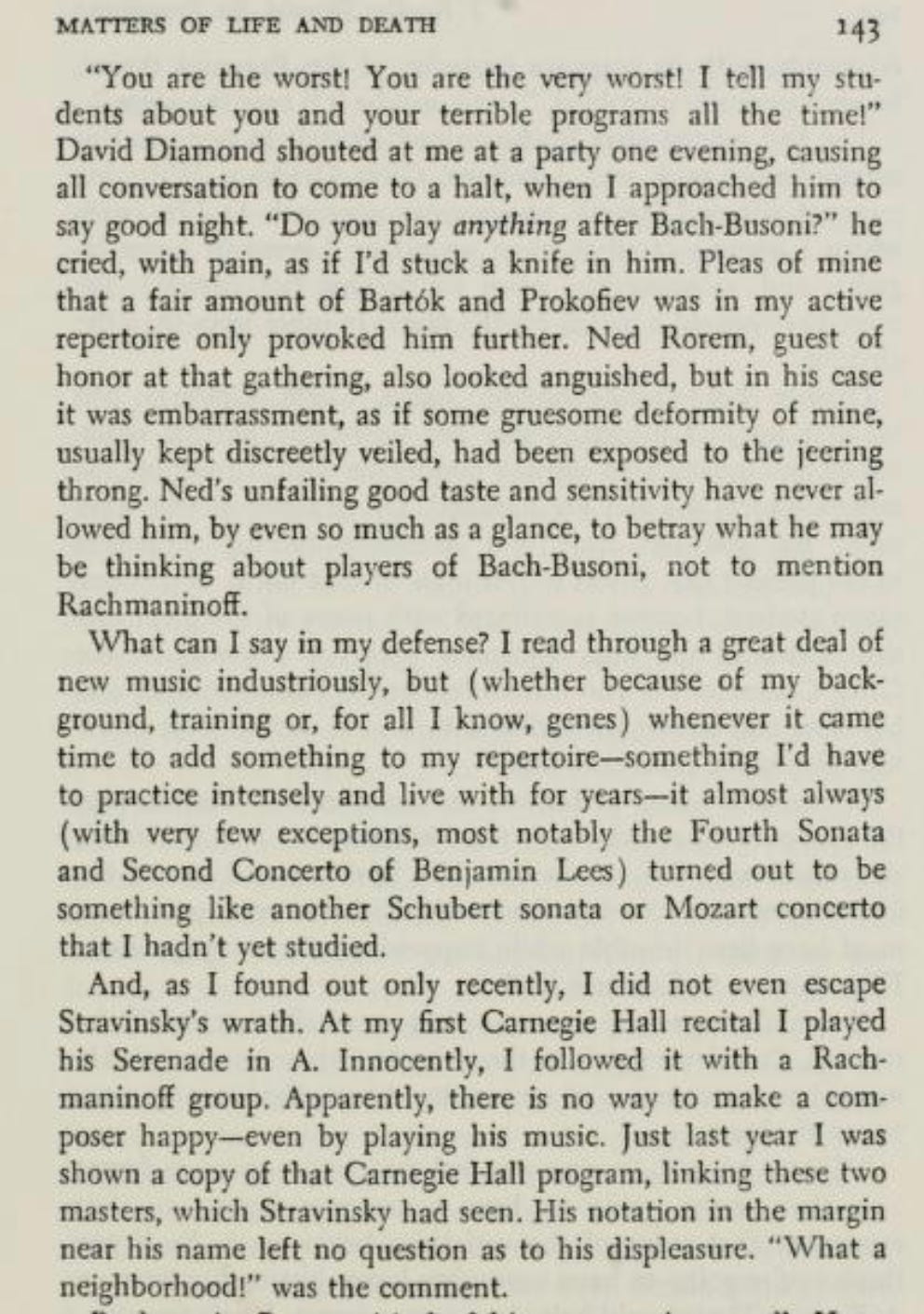

One of the “Souvenirs” celebrates famous musicians who died in the 1960s; somewhat unexpectedly included among more famous names is house favorite Booker Little.

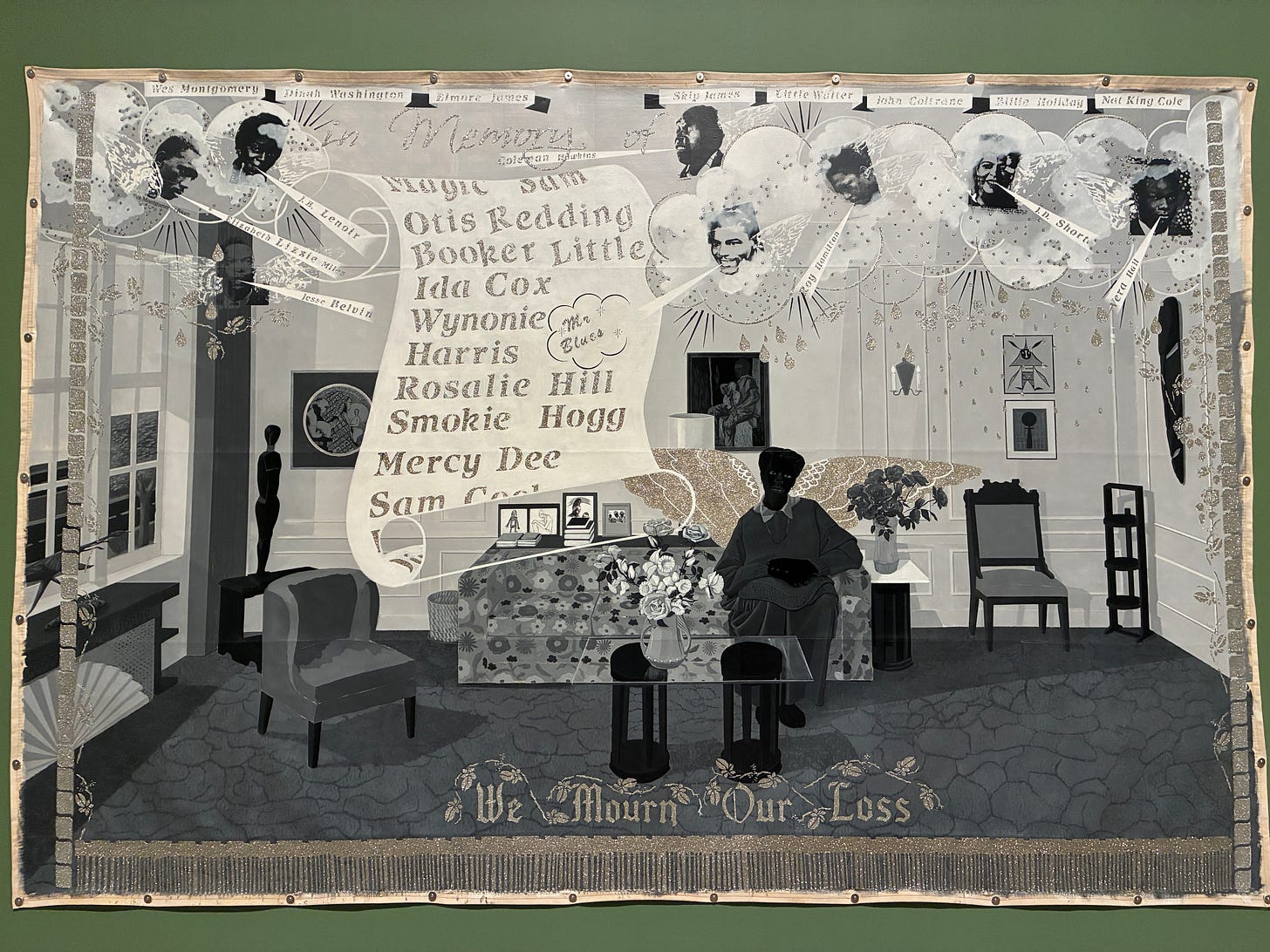

And from “Painting of Modern Life II” there is a proud cop, a work dated from right after the buzzwords “defund the police” entered the then-current political lexicon.

Sarah had previously known Marshall’s work much better than myself, but I’m catching up, for I left the exhibit exuberantly clutching the related coffee-table book. (The only other occasion where I’ve made a similar purchase was at MOMA after a Gerhard Richter retrospective.)

There is quite simply nothing like seeing Shakespeare in London, and both of us were left reeling by the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Twelfth Night at the Barbican.

Director: Prasanna Puwanarajah

Designer: James Cotterill

Music: Matt Maltese

starring

Freema Agyeman (Olivia)

Michael Grady-Hall (Feste)

Gwyneth Keyworth (Viola)

Samuel West (Malvolio)

Daniel Monks (Orsino)

Once again I am left with the impression that this playwright from so many centuries ago wrote scenes that still manage to encompass all of human behavior today. Puwanarajah’s contemporary take is hilarious and profound. Quite literally: I laughed, I cried.

We’d both rank both activities as a “must” for those in London. Twelfth Night is on through January 17, Kerry James Marshall until January 18.

In terms of the American public’s interest in classical music, the Eisenhower and Kennedy years were the height, a time when many young virtuosos produced beautiful and even bestselling LP records while playing well-attended concerts all over North America.

Several of the most imposing and virtuosic postwar American classical pianists also suffered more than their share of bad luck.

William Kapell: born 1922; died at 31 in a 1953 plane crash

Julius Katchen: born 1926; died of cancer at 42 in 1969

Gary Graffman: born 1927; mostly lost the ability to play with both hands in later 1970s

Byron Janis: born 1928; derailed by arthritis in the early 1970s

Leon Fleisher: born 1928; mostly lost the ability to play with both hands in early 1960s

John Browning: born 1933; had many wilderness years starting in the 1970s

Van Cliburn: born 1934; a major career drifted off in the 1970s

Gary Graffman died last month at 97, and thus the last living link to this American era is severed. (The great Bella Davidovich was born 1929 and is still alive; however, she emigrated to America from Russia in 1978.)

In addition to his work as practitioner and eventually as teacher (high-profile students included Lang Lang and Yuja Wang), Graffman also published an 1981 memoir, I Really Should Be Practicing, which included reminiscences of conductors Toscanini and Szell, violinist Heifetz, and scores of pianists. Graffman admired Hofmann and Rachmaninoff on the concert stage, but felt more influenced by performances and advice given by Schnabel, Rubinstein, Serkin, and Horowitz (Graffman studied intimately with the last two).

In terms of his recorded legacy, perhaps the concertos of Rachmaninoff and Prokofiev are standing the test of time more than the solo repertoire. Sviatoslav Richter thought the Graffman LP of Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini (with NY Phil and Bernstein) was excellent, going as far to declare that he wouldn’t play the work himself after hearing Graffman.

At the time of his first ascent, Graffman did not program much modern music, and from this vantage point it seems rather a pity that so little midcentury repertoire is represented in his discography alongside conventional LP recitals of Chopin, Schubert, Liszt, and etc.: Indeed, the only American composer recorded by Graffman in the early years was the somewhat obscure Benjamin Lees. An amusing page from I Really Should Be Practicing confronts this topic head on:

However, I just now learned there is a terrific late entry, the Alfred Schnittke Piano Quintet, a great work, recorded in 1998 with the Lark Quartet. As this piece of introspective chamber music was not really a virtuoso undertaking, Graffman was able to coax his injured right hand into action, and the result was a sensitive and stylistically acute performance.

Footnote one: My old DTM post Write It All Down name-checks Graffman and Benjamin Lees. (“While Benjamin Lees is also in the Prokofiev to Bartók tradition of Sessions to Kirchner, most of what I’ve heard is a comparatively ‘easy’ listen with the composer making a direct and uncomplicated argument. (Perhaps Lees shares something with the Argentinian Alberto Ginastera.) Gary Graffman was Lees’s high-powered advocate, and Lees credited Graffman with good ideas for the pulsating Sonata No. 4 (1963).”)

Footnote two: Graffman made headlines in 1964 when he canceled a concert in Jackson, Mississippi. A chapter of his memoir is dedicated to this event, and while the whole story is complicated, the short version is simple: Graffman refused to play in a segregated hall. Due credit to Graffman for taking a stand, and apparently it was the beginning of some local change, for he was the first classical artist to cancel on a series that was already under pressure from the jazz and popular music community. (1964 NY Times article.) The memoir makes it sadly clear that Graffman’s booking agent, Columbia Artists Management (a major player in the industry until the Covid pandemic), did not support the pianist. After the dust settled, Graffman needed a new agent.

(In a related topic, there have been many recent cancellations after the renaming of the Kennedy Center to the Trump-Kennedy Center.)

I wasn't in London but I was lucky. Despite my wife being in bed, still fighting off whatever she picked up at the Japanese place we went to for Christmas, downstairs I finally caught up with the programming available via the Cleveland Orchestra's Adella streaming service, specifically this: conductor David Robertson leading the orchestra through Copland's Suite from Appalachian Spring; Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue; Ellington's New World A Comin'; and Copland's Suite from The Tender Land. With Marc-André Hamelin performing on both the Gershwin and the Ellington. Great start to the New Year. I had seen this concert in person, but watching the performers, including a favorite local sax man, Howie Smith, via camera close-ups was a much more intimate and moving experience.

KJM is producing beautiful and important work. If any Baltimore-area gigs are on your schedule (An die Musik?), the Amy Sherald exhibition @ Baltimore Museum of Art is worth a look—the paintings, short film and coffee table book are all fantastic!