Guest post from Thomas Morgan: A UNIVERSE OF POSSIBILITIES WITHIN THEIR RESOURCE CONSTRAINTS

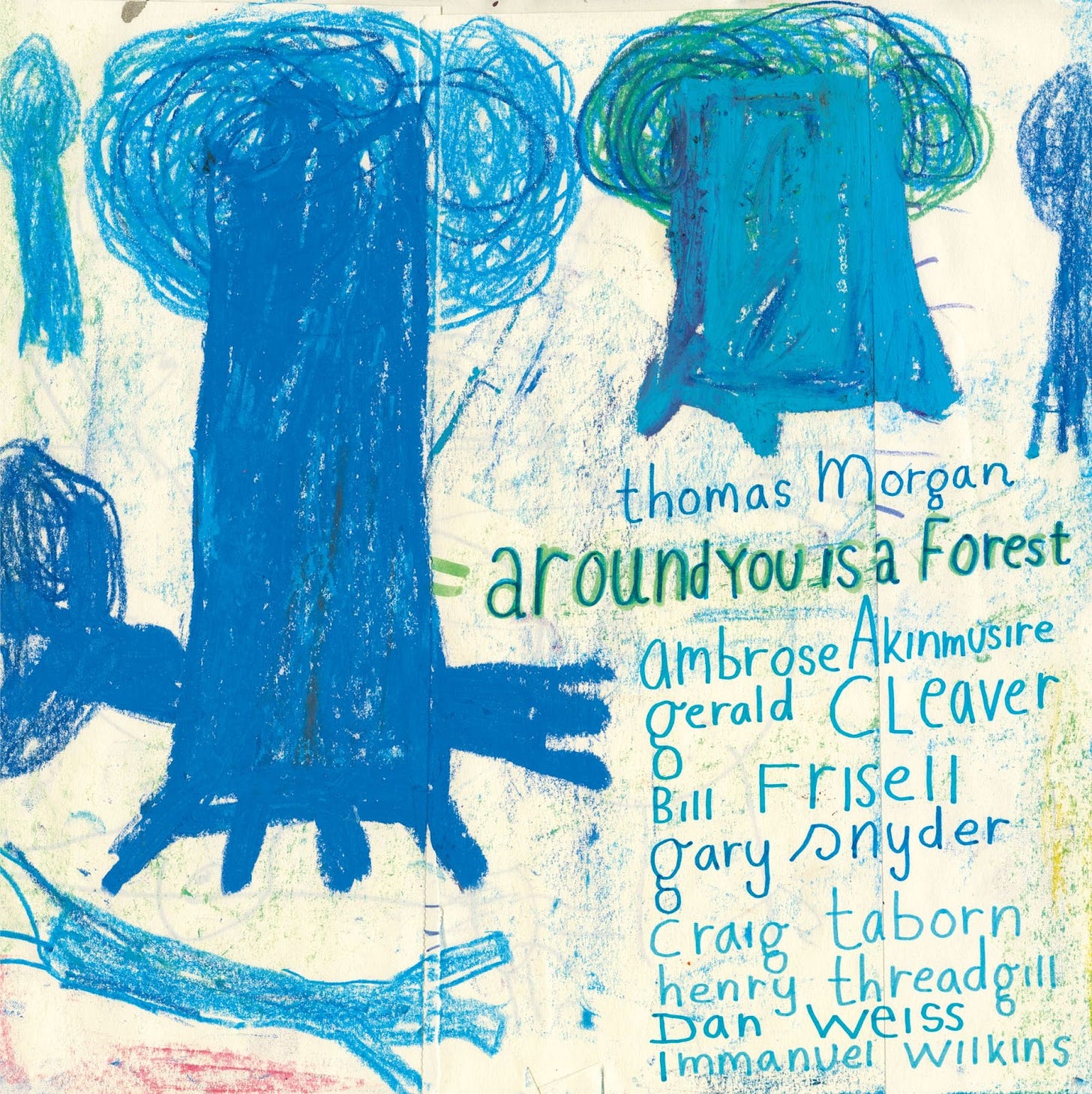

[all about the new album AROUND YOU IS A FOREST]

(Thomas Morgan is acclaimed as one of the great bassists of the era, he is both rooted and free, and boasts an exceptional lyrical sensibility. His first album is not exactly a normal bass-led jazz album, though. Indeed, Around You Is a Forest requires quite a bit of context. Strap in: I just LOVE this essay! “Jazz musicians are music hackers.” Yeah, Thomas! The music is fabulous, too. — E.I.)

[Around You Is a Forest is available in many ways from many places. Link.]

a universe of possibilities within their resource constraints

(file under: Loveland Music, MacPaint, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, Myst,BASIC, SimCity, cello, bass, jazz, Perl, Unix, hackers, Lisp, Emacs, GNU, free software, Scheme, recursion, IRC, net Tetris, MIDI, Conway’s Game of Life, SuperCollider, WOODS, Portola Redwoods State Park, Choose Your Own Adventure, “You are standing at the end of a road before a small brick building…”)

CURSORY EXPOSITION

My colleagues know me as a bass player. For the past 25 years, I’ve appeared in concert and recorded with well-respected jazz musicians in that capacity. There is some bass on this record—my first as a leader—but the instrument heard throughout the album is WOODS, a virtual string instrument comprising qualities of West African lute-harps, Asian zithers, cimbalom, and marimba.

WOODS is a SuperCollider-based system that I designed to generate timbres and patterns that sound natural despite their algorithmic origin. The first WOODS harmonic language is the pentatonic scale—the harmonious color palette for so much folk music of the world—including the music of zithers and lute-harps. As a mutational process transforms the melodic patterns, the harmonies become more abstract. Each track has its own mix of the wooden, metallic, and electronic timbres that follow from WOODS’s parameters, but the general effect is a self-same texture, as if WOODS were an acoustic instrument.

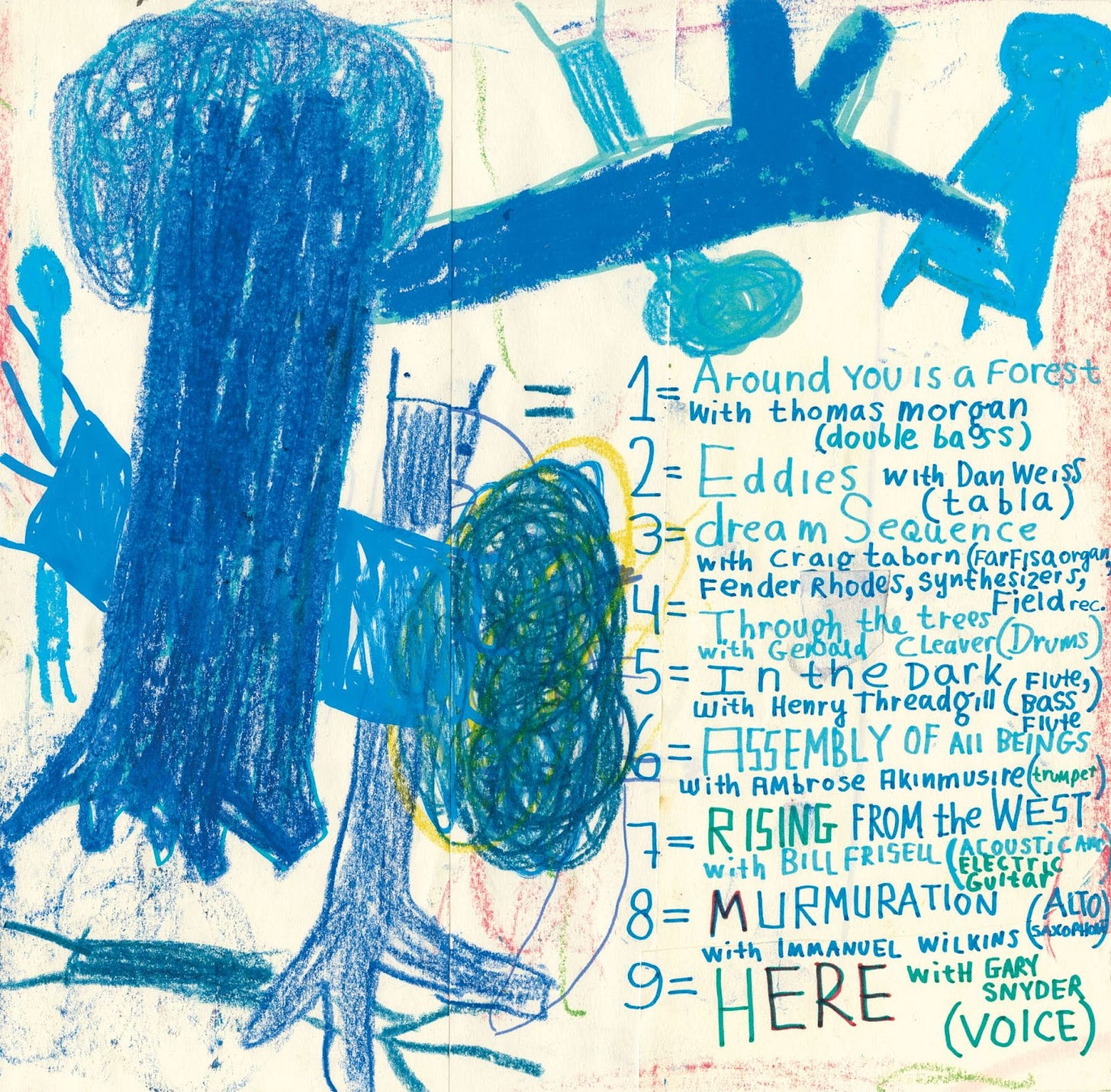

I play double bass with WOODS on the eponymous opening piece of the album, and from there, each track pairs the virtual instrument with a different artist: Dan Weisson tabla, Craig Taborn on keyboards and field recordings, Gerald Cleaver on drums, Henry Threadgill on flutes, Ambrose Akinmusire on trumpet, Bill Frisell on guitars, and Immanuel Wilkins on alto saxophone. The final duet features poet Gary Snyder, whose imagery and themes resonate through the album.

WELCOME!! IF YOU HAVE NOT PLAYED BEFORE, CONSULT THE FOLLOWING LORE.

My father, Christopher Morgan, began his career as a computer science professor at Cal State East Bay, which at the time was named for Hayward, the city where the university is located and where I grew up. Computer science was just emerging as an academic discipline, and my father was part of that first wave. His background was in math and physics, and math always seemed especially close to his heart. He wrote books on microprocessors and developed software for the remote control of scanning electron microscopes. In his spare time, he would program things like higher dimensional graphics or waveform processing software, occasionally staying up all night in a state of sustained focus.

He introduced me to computers as a toddler, starting with MacPaint on a Mac Plus. In elementary school I moved on to computer games from Where in the World Is Carmen Sandiego? to Myst. That was also when I started playing around with the BASIC source code for a snake game, which was my first glimpse of how software was put together. As a parent, my father believed in creating opportunities and removing obstacles more than direct instruction, but when I asked him, he showed me how to edit a SimCitygame file in hexadecimal to increase city funds. Understanding how things were actually working opened up another world altogether.

By the summer before second grade, my musical path had started too, with daily sessions working through basic piano books with my mother, Carol Morgan. Music was always an important part of her life, and when she was in high school, she toured Europe with her school choir. Her feeling for melody had a lasting impact on me. She would put on records by Ella Fitzgerald and Dionne Warwick, and she introduced me to the Beatles. When my uncle came over, they would play Dvořák’s Slavonic Dancesfour-hands. As for my father, he played French horn and listened to classical composers like Haydn, sometimes whistling melodies that might have been written by those composers. My older sister Lizzie had played piano, trumpet, French horn, and oboe, in that order, and after leaving home for college she brought back mix tapes she’d made me of an exciting new kind of music, by The Pixies, REM, and The Cure.

A few months after I started piano, the local youth orchestra announced it was offering a beginning strings class. I joined immediately, switching to cello at my sister’s suggestion, and continuing in the orchestra for the next eight years. After a few years, some of my friends from church helped me get started on the guitar, and my classmate Danny and I formed a garage band duo. I played cello and electric bass, and we both played guitar, sang, and wrote songs—when we weren’t playing Super Mario Kart or wandering the canyon behind Danny’s house. In junior high, I sang in a children’s choir and recorded musical theater demos with a small version of the choir. Then, just before starting high school, I heard Todd Sickafoose play double bass at a music camp. His sound certainly made an impression: it was big, gentle, clear, and alive. I was fascinated too by the role that the bass played in the jazz big band, the way it danced with the other parts, using tension and release to color the harmonic and emotional content of the music. Soon after, my mother and I found a bass to rent, and later to buy. I’ve been playing it ever since.

A year or two earlier, when I was in junior high, my father had introduced me to the Perl programming language on our IBM PC. I had already played with ResEdit on our Mac to modify applications’ internal resources, and I had tinkered with the snake game. But Perl opened up a wider world of programming. Whatever I thought of doing, there was a convenient syntax to express it. We made regular trips to the Computer Literacy bookstore and Fry’s Electronics in Silicon Valley. We created our own home pages and used NCSA Mosaic to access the early web over a high speed ISDN line. He made me an account on his university’s Sun workstations, and later brought home for me a Sony workstation so ancient it had a built-in tape drive for backups.

These computers ran Unix, which made sense to me in a way other operating systems never did. That was a benefit that easily outweighed the near-obsolescence of the Sony. The command line interface made it simple to automate tasks, and programs were typically composable, allowing you to do complex things by pipelining small programs together—or extensible, so that you could add new capabilities to larger programs. Working with Unix, I now saw computers not just as tools with fixed functionality, but as systems to be reshaped by the user. That’s what I find beautiful in computers: Their functionality is highly malleable, offering a universe of possibilities within their resource constraints.

One day, my father handed me the book Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution by Steven Levy, which heightened my appreciation for programming, especially for the Lisp programming language and the culture that it grew out of. Envisioned in 1959 by John McCarthy at MIT, Lisp stands for “LISt Processor,” and it was designed for the symbolic artificial intelligence research of its era. Its spare syntax, contrasting with Perl’s plethora, counterintuitively helps make it flexible and expressive. With code that looks just like its data, Lisp achieves a level of metacircularity—code operating on code just as readily as on any other data—unique among programming languages. I had been using vi—the Berkeley Unix text editor—but the fact that GNU Emacs, the other major Unix editor, could be customized and extended with Lisp won me over. Religious wars have been fought between adherents of either of these two programs, but there has also been a productive influence—in both directions. Both are keyboard-driven and reward the user with efficient usage after the learning curve of initial study.

Emacs is part of the GNU operating system, the flagship of the free software movement. That movement, which rose up in the 1980s from the ashes of the 1970s hacker culture, is dedicated to giving users the freedom to read, modify, and redistribute programs’ source code. These freedoms foster community and ensure that programs are dedicated exclusively to serving users’ interests, unlike proprietary software, which often prioritizes other concerns. GNU programs were also more dependable and thoughtfully designed, and I appreciated the exemplary style in which they were written. Building them on my ancient Sony workstation was sometimes a slow and painstaking process, but it was worth the effort.

The hackers Levy wrote about, some of whom went on to be involved in the free software movement, were larger-than-life comic book heroes to me, almost superhuman in their skill and their dedication to building things and advancing knowledge for the common good—in stark contrast to the nihilistic and destructive connotation the word “hacker” was to take on. The Internet as I first knew it had something of their utopian spirit and was built on open standards and protocols from bottom to top. It was designed for inclusion, not enclosure. Today’s walled gardens and profit-maximizing algorithms that promote misinformation and fracture societies strike me as antithetical to the hacker ethic. At the same time, free software, a manifestation of that ethic, has become nearly mainstream under the name open source—even surpassing proprietary software in many domains.

I was also inspired by friends with similar interests that I met on IRC, an open distributed chat protocol. One was orabidoo, a brilliant Catalonian programmer studying in France. He worked with cellular automata (systems of cells on a grid that evolve according to a set of rules), invented his own language, with a grammar and vocabulary, and made electronic music. For fun he created an IRC chatbot called Bot-Tom, and a networked Tetris game which he would beat me at every time we played.

In the summer before my sophomore year in high school, I took a UC Berkeley Extension course on Scheme, an elegant Lisp dialect that handles recursion efficiently. Recursion—defining a process in terms of itself—was a mind-expanding concept. It was a different way of thinking about problems, breaking them down into progressively simpler versions of themselves until the solution is reached. The professor was Brian Harvey, one of the hackers in Levy’s book. He didn’t believe in or give grades, and his class was far removed from the arbitrary rules and formalities that turned me off from my high school studies. His philosophy, that curiosity-driven exploration fuels growth more effectively than strict adherence to a standardized plan, seemed like it was straight out of Hackers—and it was.

In those same years, my relationship with music was deepening, and I fell in love with jazz. My first bass heroes were Milt Hinton, Charlie Haden, and especially Ray Brown, whose powerful and articulate sound made every note feel definitive. Thelonious Monk and Wes Montgomery inspired me just as much, and, enthralled by Charlie Parker, I borrowed an alto sax. I couldn’t get a single note out of it, so I stuck with the bass.

Steven Levy wrote about the Hands-On Imperative, the hackers’ instinct that you had to have your hands on a thing to truly understand it. He described how magical it was for them to program interactively using a relatively diminutive TX-0 computer as opposed to the more powerful but batch-processed IBM mainframes. For me, jazz represents the same magic. Whatever is shared, discovered, or invented has the potential to be applied in the very same moment or soon after. With such a tight feedback loop, ideas can compound, and the music is essentially optimized for learning as much as possible every time you play.

There’s a passionate jazz community with little hierarchy, great freedom and room for individuality, a healthy disregard for convention, and an intense pursuit of musical excellence. Whatever differences might otherwise divide people, if you dedicate yourself to your love for music, you can come together and share ideas and make something better as a group than you could ever imagine making alone.

All of this parallels the highest ideals of hacker culture. Jazz musicians are music hackers.

I moved from the Bay Area to New York to attend Manhattan School of Music. This was full immersion into jazz, with inspiring peers and elders to play with all day, every day. Soon I met Dan Weiss and Jacob Sacks, innovative and inquisitive musicians just a few years older than me. They expanded my horizons, adding Indian classical, electronic, singer-songwriter, R&B, and contemporary classical music to the jazz I already appreciated. Together they created an interactive musical language that we continue to develop as a trio.

In a college MIDI studio class, my free software leanings led me to write my own assembler for standard MIDI files using the C and Scheme programming languages, rather than use the studio’s proprietary software. I figured there was value in learning MIDI from the ground up in this way, but the teacher was nonplussed and refused to give credit for the assignments I’d completed with this assembler. It reminded me of an episode in Levy’s book where a teacher rejected a hacker’s homework because he had used his own computer program instead of the prescribed desk calculator.

Still, it was then a natural next step to try making algorithmic music with my assembler, and I experimented with musical mappings of nursery rhymes and representations of the cellular automata in Conway’s Game of Life—a game where a simple algorithm yields lifelike patterns. Although the classroom experience was frustrating, it set me on a new creative path.

I was also taking an improvisation class with Garry Dial, a superb jazz pianist and an openhearted and sympathetic teacher. He has a gift for approaching musical challenges as systematically as a computer programmer. To show solidarity after my MIDI assembler project was dismissed in the MIDI studio class, he offered to let me do a midterm test—applying specific interval patterns to John Coltrane’s “Countdown”—with my MIDI assembler instead of on bass. He was surprised when I took him up on the offer; only then did I realize he had meant it mostly as a joke.

In my first year of college, Garry had recommended me to his neighbor, the drummer Joey Baron, and we quickly formed a musical connection despite my inexperience. I played with his band Killer Joey when his regular bassist, Tony Scherr, was busy. Joey puts the highest emphasis on blend, and he teaches by example how electrifying true connectedness can be in a band. When I was packing for my first tour—in Europe with Killer Joey—he also taught me how to travel light, a habit that has made touring a lot smoother over the years.

As school sessions and one-off gigs gradually progressed into tours and recordings—with leaders such as Dave Binney, Steve Coleman, John Abercrombie, Masabumi Kikuchi, and Paul Motian—I continued making friends who inspire me. These include the musicians who have joined me on Around You Is a Forest, and guitarist Jakob Bro, whose record label is releasing the album in an outgrowth of our musical journey together. This journey played a part in Jørgen Leth’s documentary Music for Black Pigeons, which began with our 2015 quartet tour of Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Scandinavia with Lee Konitz and Bill Frisell. In a trio with Joey Baron, Jakob and I play his timeless hymn-like melodies over rich, imaginative textures, and in a septet with Joe Lovano we pay tribute to the music of Paul Motian.

In April 2012, around a decade after I’d built my college MIDI assembler, I discovered Overtone while reading Hacker News in an attic hotel room in Paris. Overtone interfaces with the SuperCollider real-time audio server, which is a powerful audio synthesis engine. Written in the modern Lisp dialect Clojure, Overtone represented access to audio synthesis and processing from Lisp, a perfect intersection that rekindled my interest in algorithmic music, promising greater control over expressive nuances compared to my MIDI assembler.

(defn change-random-note-octave “Raise or lower a random note in ‘notes’ by one octave.” [melody-history notes] (update-rand notes (λ [note] (update note :pitch (λ [pitch] (when pitch (let [p (+ pitch (rand-nth [12 -12]))] (if (in-range? p) p pitch))))))))a Clojure function

In 2014, the saxophonist Ohad Talmor invited me to compose music for and play a residency at SEEDS Brooklyn, his living room venue, which was my first time playing all original music as a bandleader. On the residency and on further gigs, Dan Weiss played drums and Pete Rende drew hauntingly beautiful sounds from analog synthesizers, including the classic Yamaha CS-70 and Prophet-5.

If jazz musicians are music hackers, Dan is one who particularly embodies the intensity and ingenuity of computer hackers. He seems to defy the laws of physics in the way Levy tells us the legendary hacker Bill Gosper did with his counterintuitive ping-pong shots. At the same time, Dan can focus on even the simplest elements with great patience, drawing from them more than anyone else can see.

For the residency, I composed most of the music with Overtone using deterministic algorithms, making demo recordings with sampled versions of our instruments. Some short pieces were created by mapping text to music, with pitches and rhythms derived from the numerical representation of each letter, symbol, or space. It wasn’t far from the system I’d previously made with my MIDI assembler.

THE MAKING OF WOODS

In the next few years, I grew curious about using Overtone for synthesis rather than samples, guessing that working from more primitive elements might lead to more nuanced expression. The algorithm that caught my eye was Karplus-Strong, which simulates the plucking of a string and is built into SuperCollider. With my background as a string player, using this to expressive effect looked like a relatively approachable problem, and experiments with it resulted in the WOODS virtual instrument.

WOODS developed over the course of the music on Around You Is a Forest, initially sounding similar to mallet instruments like the cimbalom or marimba, then resembling the plucked string sounds of the West African ngoni and kora, and finally taking on vibrato that brings to mind the Asian gayageum and koto. But it wasn’t so much intended to emulate these specific instruments as to sound largely but not entirely realistic, like an acoustic string instrument with touches of the fantastic.

WOODS was temporarily called “pluck,” then “garilom,” a portmanteau of GAyageum, maRImba, and cimbaLOM. My producer, David Breskin, later nicknamed it “the Thombot.” That reminded me of Bot-Tom, the IRC chatbot my friend Roger had created, and naming the instrument after the bot also crossed my mind. Eventually I arrived at

WOODS,

a recursive acronym which stands for WOODS Often Oscillates Droning Strings.

“Droning” describes the somewhat thicket-like music on “Around You Is a Forest,” which mostly—though not always—has WOODS repeating and mutating short phrases over long spans of time.

As recursive (self-referential) programming paradigms are idiomatic to dialects of Lisp, especially Scheme, recursive acronyms are a fun part of Lisp culture. Because a recursive acronym’s expansion contains the acronym itself, it expands infinitely:

$ expand-woods WOODS > step (WOODS Often Oscillates Droning Strings) > step ((WOODS Often Oscillates Droning Strings) Often Oscillates Droning Strings) > step (((WOODS Often Oscillates Droning Strings) Often Oscillates Droning Strings) Often Oscillates Droning Strings) > step ((((WOODS Often Oscillates Droning Strings) Often Oscillates Droning Strings) Often Oscillates Droning Strings) Often Oscillates Droning Strings) > continue Expanding...OutOfMemoryError

I recorded the WOODS tracks that appear on the album in 2016—the duet partners would overlay their improvisations later—but from that time on I kept getting busier playing bass, and this project drifted into the background. In particular, I was playing more often with Bill Frisell, who makes music as graceful, soulful, and personal as one can imagine while never seeming entirely convinced that he knows how to play the guitar. Our first meeting was a rehearsal with Joey Baron in 2002, then a still-unreleased recording session with Kenny Wollesen and a fifty piece band, but it was Paul Motian’s final album, The Windmills of Your Mind, that made a lasting connection.

WOODS was again in my thoughts during the pandemic. I brought the instrument back to life and started planning Around You Is a Forest. Though I slowly returned to a full touring schedule, I concluded that even if there was no perfect time for it, it was important to me to finish and release the music.

I asked David Breskin to produce the album, and it was his suggestion that every piece be a duet with a different partner, each playing a different instrument. He was a helpful advisor as I matched partners to pieces, and he always had metaphors or stories ready for the musicians in the studio, bringing fresh imagery into new takes. “Murmuration,” for example, included many layers and could have gone in many directions in post-production. David’s advice proved valuable as I edited the audio. The album is both more focused and more texturally diverse because of his participation.

When it comes to making music with computers, the possibilities are all but endless. SuperCollider itself provides hundreds of unit generators, which are the building blocks of audio synthesis and processing. Do artists want to transcend all limitations, or do resource constraints paradoxically increase our capacity for expression? These are not new questions but they take on special relevance in our resource-rich digital age. WOODS is a possible response to abundance: an exploration of one small corner in a vast timbral terrain.

Just as Lisp’s uniformity of syntax facilitates metaprogramming, which is a reshaping of the language itself, WOODS plays within a specific range of timbre and texture, reshaping our perception. A jazz rhythm section creates an immersive flow that dilates time, making an hour feel like minutes, and WOODS is a kind of rhythm section for the duet partners on Around You Is a Forest. In addition to drawing us outside the ordinary flow of time, its textural homogeneity attunes our ears to its own nuances—a metallic clink or muted tap here, a shift in rhythmic emphasis there—and what’s more, it highlights the duet partners’ inventive solos.

GUIDE TO CHARACTERS AND LEVELS

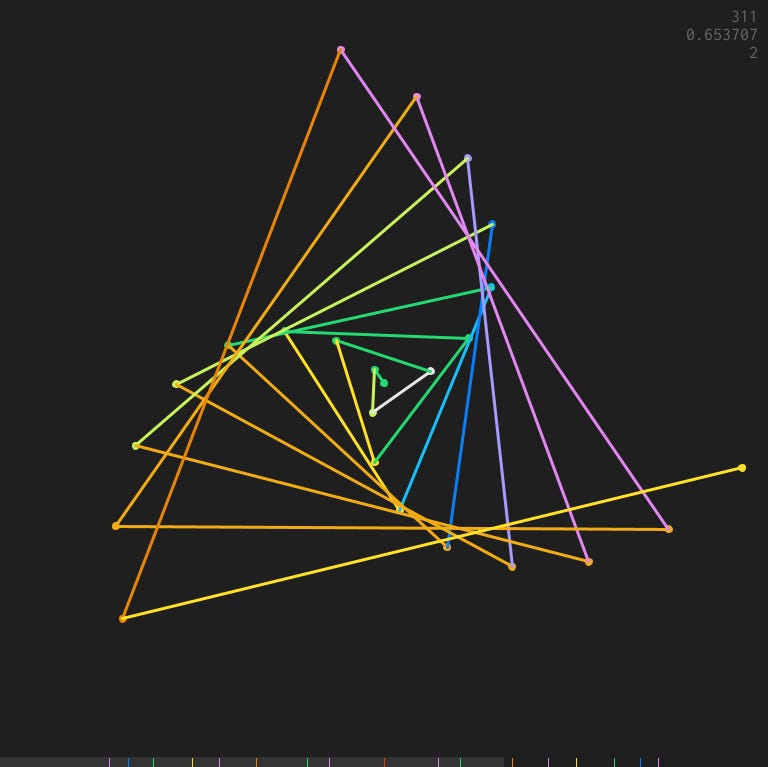

The sequence of tracks in the final album is not identical to the order in which they were recorded. It seems worth recounting the journey chronologically, especially since the way the WOODS parts were made changed after the first composition was completed. At first, I used a direct application of “Tailspin,” a generative animation by Swedish game designer Erik Svedäng. The animation features dots spaced at regular intervals from the center of the canvas, each connected to its neighbors by a line segment. Initially lined up in a row, the dots then revolve clockwise, with speeds proportional to their distances from the center. As they move, a variety of shapes emerge, starting with spirals and evolving into slightly imperfect concentric polygons, stars, and more. In a full cycle, triangles appear twice (dividing the cycle into three equal parts), squares three times, pentagons four times, and so on. Here it is spiraling toward concentric triangles:

003 DREAM SEQUENCE += CRAIG TABORN

The WOODS part was created by tracking the animation all the way through, the music continuously reflecting the shapes in the picture. Though the animation is deterministic, the music is probabilistic, and I made adjustments in real time in response to the musical output. WOODS improvised melodies while I improvised its code and parameters. Much of the fun in this process was that I was continually surprised by the music despite my familiarity with the programming that generated it.

Everyone who works with Craig Taborn trusts him to bring something unexpected to the table. In his home studio, Craig conceptualized the piece as five distinct scenes, adding electric and electronic keyboards as well as field recordings of rain, wind, crickets, and birds captured in a Balinese town surrounded by rainforest.

Craig matches intellectual curiosity and rigor with heart and vulnerability. I played extensively in Craig’s trio with Gerald Cleaver from 2007 to 2014, and the music changed in surprisingly fundamental ways from night to night as we embraced the particularities of each context. Craig’s trust and resourcefulness allow the music to breathe, to be “here.”

004 THROUGH THE TREES += GERALD CLEAVER

The rest of the music originated from single phrases created by the “Tailspin” process as opposed to continuous tracking of the animation. “Through the Trees” was the next piece if we sort by creation date. I recorded WOODS in my hotel room after a recording session with Jakob Bro, Palle Mikkelborg, and Jon Christensen which was released by ECM as Returnings. Excited to share what felt like a step forward, I played the track for Jakob and Palle in the taxi to Oslo airport the next morning. They encouraged me to keep going.

When I eventually decided to make an album from the WOODS recordings, inviting Gerald Cleaver to play was my very first thought because of his masterful creativity in shaping improvisations over long time spans. WOODS itself was fundamentally inspired by the patience and potential energy of Gerald’s playing.

In “Through the Trees” and all the following pieces, a seed phrase evolves over a long period by accumulating tiny mutations. Like the “Tailspin” process, this second procedure was also probabilistic, and it involved adjusting the likelihoods of the various kinds of mutations in real time.

The pieces made with this process were quite long in their original forms—“Through the Trees” was over 30 minutes—and my partner Emi Makabe and the engineer Nate Mendelsohn edited the WOODS tracks before the duet partners improvised with them. Emi has supported this project from the very beginning, her discernment and encouragement helping me keep on course. It might never have been finished without her. I’m grateful to Nate as well for his complex and delicate edits to the WOODS tracks.

Character and quality of sound can be the first invitation into an album. Recording engineers Philip Weinrobe, Michael Coleman, Adam Muñoz, David Luke, and Tyler Hicks artfully captured what the duet partners played. Joseph Branciforte edited their parts, in some cases painstakingly recreating edits I had made in another DAW, and mixed the album. He drew on his wealth of experience as an engineer, musician, and electronic music composer, making creative panning choices, adding outboard effects to WOODS, and finding the right reverb for each moment.

008 MURMURATION += IMMANUEL WILKINS

“Murmuration,” the second piece created with the mutational process, features Immanuel Wilkins layered eight times. Take after generous take, the music seemed to burst out of him. His vibrant, funky, and tightly coordinated alto sax lines call to mind a flock of birds soaring, swirling, dispersing, clustering, and quickly changing direction.

WOODS provides propulsion and sounds most like an ngoni here, a resemblance I recognized when I heard the instrument played by Don Cherry.

006 ASSEMBLY OF ALL BEINGS += AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE

On “Assembly of All Beings,” Ambrose Akinmusire creates blurry sound textures that then come into focus, as if in a movie. He takes his trumpet beyond conventional vocabulary to summon dinosaurs, elephants, and horses, and one might imagine these animals joining their voices in an evening performance. Ambrose and I first played together as high school students in the Bay Area, touring Japan and performing at the Monterey Jazz Festival with a student big band. His integrity, already apparent then, has led him to the practice of an original and deeply resonant art.

The title comes from Gary Snyder’s book The Practice of the Wild, which raises the possibility of human beings reactivating our membership in the wholeness that is the wilderness. On this piece, WOODS resembles a steel-stringed zither, somewhat like a cimbalom.

While creating the WOODS part, I implemented a system for saving any point in the musical development as a new seed, and then switching between seeds in real time. Music made with this feature can take on a tree-like structure, branching off in multiple directions and potentially hopping from branch to branch.

002 EDDIES += DAN WEISS

As a child I took camping trips to Portola Redwoods State Park with my friend Paul and his family. Running through the forest was a creek that the two of us would explore all day long, crossing on logs and rock paths. For me “Eddies,” with Dan Weiss on tabla, conjures up the flow of water around rocks in a stream.

I made wider use of the new save/restore feature, resulting in improvisatory changes of meter and phrase length that set the piece apart from the others. They yielded a dynamic rhythmic current that Dan navigated with both ease and playfulness. The tabla is sometimes an organic extension of the music’s unpredictable flow, and sometimes a stable bedrock against which the surface dances.

The seed from “Through the Trees” reappears as one of several seeds for this piece, and the two pieces were recorded on the same day.

007 RISING FROM THE WEST += BILL FRISELL

“Rising from the West” features Bill Frisell on acoustic and electric guitars. Bill grew up in the West, in Colorado, and I grew up on the West Coast. We’ve both ended up on the East Coast, in Brooklyn. The title might signify a reversal of the natural order, with the day’s light moving from dusk to dawn. Time often flows backwards in the imaginative effects Bill creates with his loop pedal. Memory is also a movement backward in time, and in conversation, Bill exhibits a particularly rich inner life of memories. Rather than lock him in the past, they deepen his creativity as they intertwine, coalesce, and rise into transcendence.

For the final three pieces—“Around You Is a Forest,” “Here,” and “In the Dark”—I implemented a feature to save WOODS’s improvisations so they could be refined, rearranged, and re-recorded. With this feature, I edited their long unfolding developments into tighter forms, making these the shortest pieces on the album.

005 IN THE DARK += HENRY THREADGILL

Henry Threadgill is among the most original musical thinkers alive. I was fortunate enough to record with him in one of his projects, and equally fortunate that he agreed to take part in this one. He recorded two layers, the first on bass flute, and the second on flute without listening to the first. I still can’t understand how he wove them together thematically, rhythmically, and harmonically, somehow seeing “In the Dark.”

009 HERE += GARY SNYDER

While I was programming and recording WOODS in 2016, I saw the Gary Snyder poem “Here” on the New York subway and felt right away that it spoke to the music I was making. I listened to an NPR interview that Snyder gave, sampled his reading of the poem from the interview, and wove it into a WOODS piece that was in progress. As the poem progresses, WOODS takes some of its furthest stretches into unexpected and complex harmony.

The poem has cosmic and existential themes, and for me it brings up a question: Do we need to question why we are here, or is it enough just to be here?

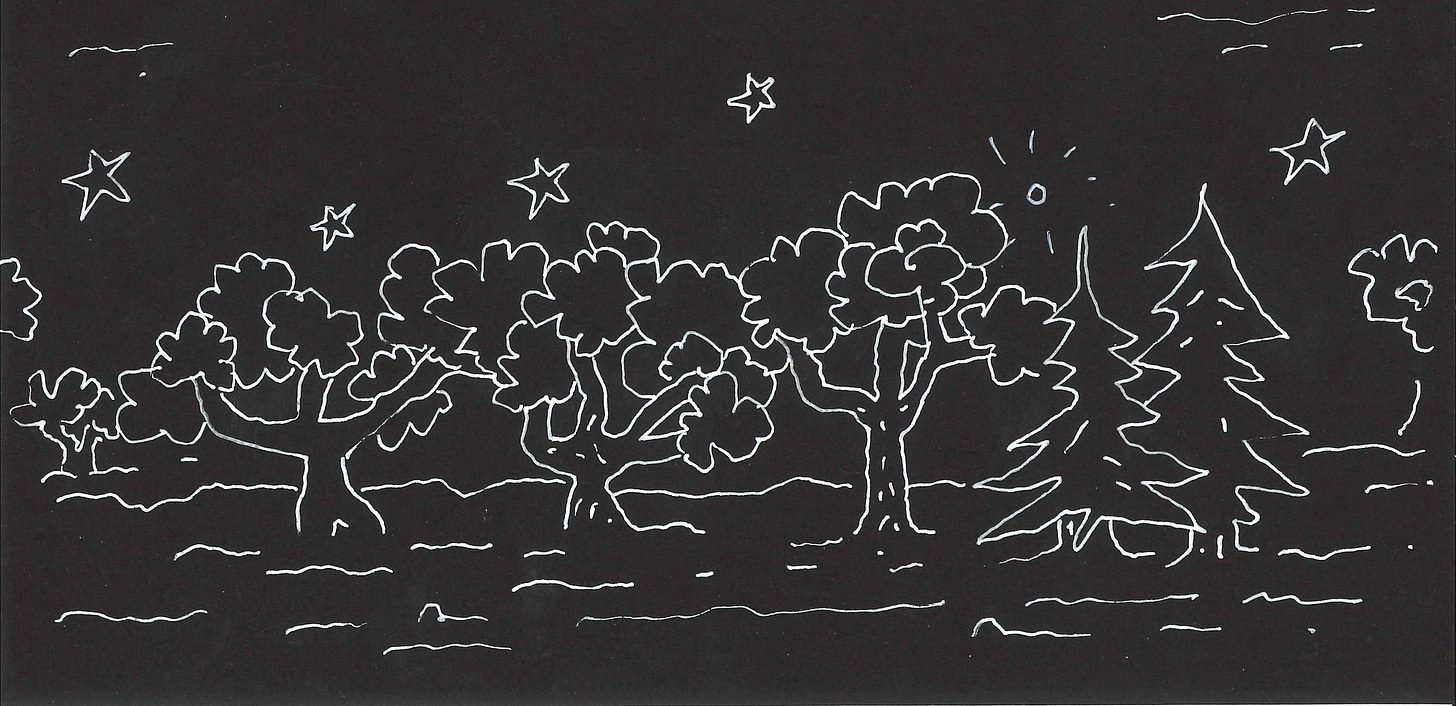

I’ve come to see WOODS, particularly in the pieces that unfold slowly over long time spans, as akin to geological or cosmic processes. The duets, then, are reflections of how each human partner exists and relates to a nature-like environment or process in their own way. In the poem, a planet shines through the trees—we see the cosmos from our human vantage point.

At the same time, the partner musicians on the album show us how to be here. As they improvise in the moment, there is only being, and perhaps there is no need to ask why.

001 AROUND YOU IS A FOREST += THOMAS MORGAN

Finally, the bass.

The opening of the 1976 text-based computer game Adventure is famous: YOU ARE STANDING AT THE END OF A ROAD BEFORE A SMALL BRICK BUILDING. AROUND YOU IS A FOREST. A SMALL STREAM FLOWS OUT OF THE BUILDING AND DOWN A GULLY.

On the title track of the album, “Around You Is a Forest,” my own acoustic instrument is surrounded sonically by WOODS. I can picture WOODS’s notes bubbling up to the surface in an onsen occupied by a bear.

On another level, a forest is a community, where knowledge and nutrients are shared through root systems. In that sense the musicians on this album are some of the trees that teach and nourish me and all the rest of the forest.

Taking still another perspective, the image of trees in “Here” grounds the music in our human reality, as the poem shows us the universe through their branches. WOODS is made up of code, an abstraction devoid of physical form, but there is always a human element in its operation.

In my childhood I enjoyed Choose Your Own Adventure books, the concept of which coincidentally also dates back to 1976, and I played Oregon Trail on an Apple IIe in an elementary school class. Though my experience with Adventure is more limited, its opening is an iconic piece of computer history, and it puts the player straight into the scene.

YOU MAY NOW CONSIDER YOURSELF A “SEASONED ADVENTURER.” YOUR STEREO IS NOW ON. PRESS PLAY TO ENTER THE WOODS.

—Thomas Morgan, May 2025

Shuja Haider and Ethan Iverson provided invaluable editing for this essay —TM.

love reading about the process and history, revealing as it has been

Incredible essay! as a longtime hacker myself who's done some work with Overtone via Clojure, this is just so incredibly cool to read!!!