TT 371: Four Bossas and a Shuffle

"Blue Bossa," "Recorda-Me," "Recado Bossa Nova,""Ceora," and "Right Off"

Much pre-1960s jazz was informed by Cuban music and other aligned sounds from the nearby island communities including Puerto Rico, Trinidad, and Haiti.

In the ‘60s, the Cuban theme certainly continued. I just listened to Blue Mitchell’s fabulous “Fungii Mama” with Chick Corea and Al Foster on 1964’s The Thing to Do; in the liner notes Ira Gitler calls the beat “from the West Indies.”

However, for the first time, that decade saw an infusion of Brazilian know-how. Bossa Nova was the new sensation, and composers like João Gilberto and Antonio Carlos Jobim had translated something of the vertical sonorities of bebop and west coast jazz onto the guitar. With that kind of harmony built into the genre from the git-go, Bossa Nova was a perfect fit for the jazz cats. (The “A” section of Jobim’s “Wave” can even be seen as a Charlie Parker-styled 12-bar blues.)

Stan Getz scored two massive back to back hits with Jazz Samba and Getz/Gilberto in 1962 and 1963, and suddenly everyone from Coleman Hawkins and Gene Ammons to Zoot Sims and Paul Desmond had to do a Bossa Nova album.

Joe Henderson was notably interested in Bossa Nova, and his debut LP Page One from 1963 includes two of the most famous examples written by a jazz composer, Kenny Dorham’s “Blue Bossa” and Henderson’s own “Recorda-me.”

Dorham’s comments in the liner notes are intriguing:

Blue Bossa — a mystic Kenny Dorham original with an authentic feeling of melancholy and buoyancy, and easy structure to follow, and on of the best of Joe Henderson’s solos.

Recorda-Me — which in Portuguese means “remember me,” is and 16 plus 16 composition which was written in 1955 right after he came out of school. It is a Bossa Nova tune using jazz techniques in design which maintain the Brazilian feeling and buoyancy.

This was not Dorham’s first attempt to get a Brazilian feeling in his music, for both “Una Mas” and “Sao Paulo" from 1963’s Una Mas (1963) feature Bossa Nova beats. (The rest of the Una Mas band includes Joe Henderson, Herbie Hancock, Butch Warren, and Tony Williams. More on Tony Williams below.)

Dorham describes his own “Blue Bossa” as “mystic.” Merriam Webster defines “mysticism” as “the belief that direct knowledge of God, spiritual truth, or ultimate reality can be attained through subjective experience (such as intuition or insight).” Perhaps Dorham is suggesting the whole-hearted embrace of Bossa Nova by the jazz cats was a matter of intuition rather than study.

Dorham also says “Recorda-me” was written in 1955. I’m not sure what Bossa Nova records Joe Henderson would have heard that early, probably Henderson wrote the theme at that time and added the rhythm later. (For whatever it’s worth, Dorham’s “Una Mas” was recorded as the swinger “Us” on 1961’s Inta Somethin’.)

At any rate, the melody of “Recorda-me” features a profile not unlike the melody of Bronisław Kaper’s “Invitation” from 1950, wide-ranging and ending on a sixth above a minor seventh, a striking dissonance.

JoeHen played “Invitation” a lot, it is almost a “Joe Henderson tune” in the common practice jazz repertoire. (If “Invitation” is called at a jam session, it is automatically played the way Joe Henderson played it, it is not played in the manner of John Coltrane or Quincy Jones.) “Recorda-me” and “Invitation”: A sixth over a minor seventh seems to be part of the “Joe Henderson sound.”

I just love the way McCoy Tyner, Butch Warren, and Pete La Roca play the time on “Blue Bossa” and “Recorda-Me.” To my ears, Tyner and Warren are in a fairly direct and spiky Cuban bag, while La Roca is putting his own spin on the basic Brazilian drum style heard on Jazz Samba and Getz/Gilberto. La Roca’s right hand is tracing fast eighths on the snare with a brush, the left is freely interpreting the Bossa Nova clave with a cross-stick. At times La Roca sneaks in a double click on the cross-stick. Just gorgeous.

Unfortunately, both “Blue Bossa” and “Recorda-Me” have been played poorly and inaccurately by innumerable legions of inexperienced jazz students. There are many walking wounded in the annals of jazz education, but “Blue Bossa” seems to have suffered actual extinction at the professional level. Some day we may have to answer for our sins.

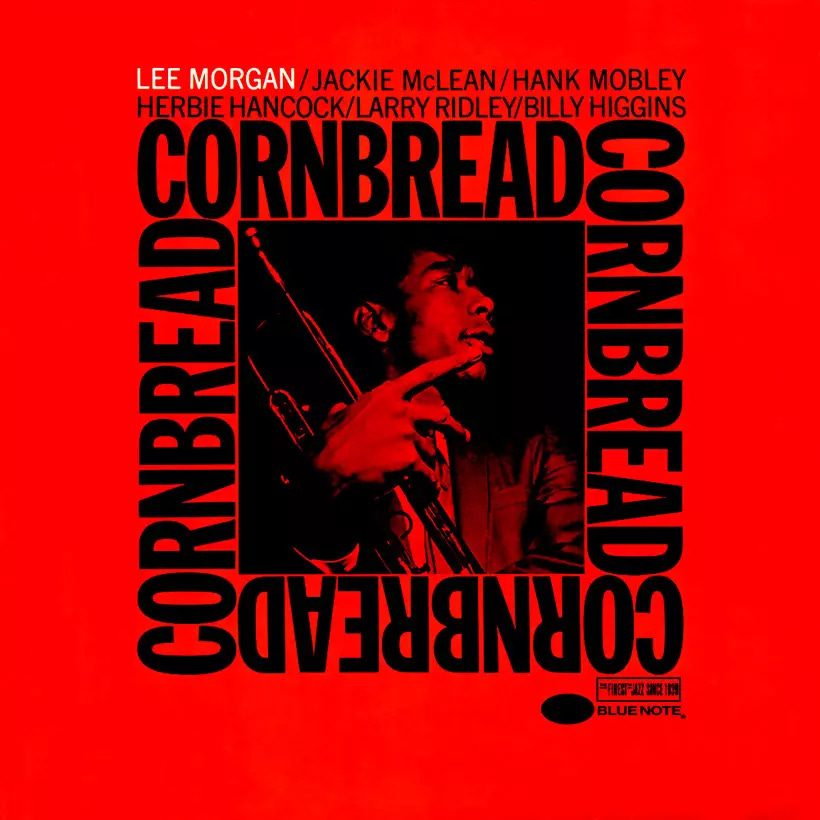

Lee Morgan was constantly in the Blue Note studios during the 1960s. Indeed, one way to look at the label’s music of that decade is just through the lens of Lee Morgan, who recorded the biggest jazz hit for Blue Note, “The Sidewinder,” alongside bushels of superb hard bop, not to mention experimental dates with Andrew Hill, Grachan Moncur, and McCoy Tyner.

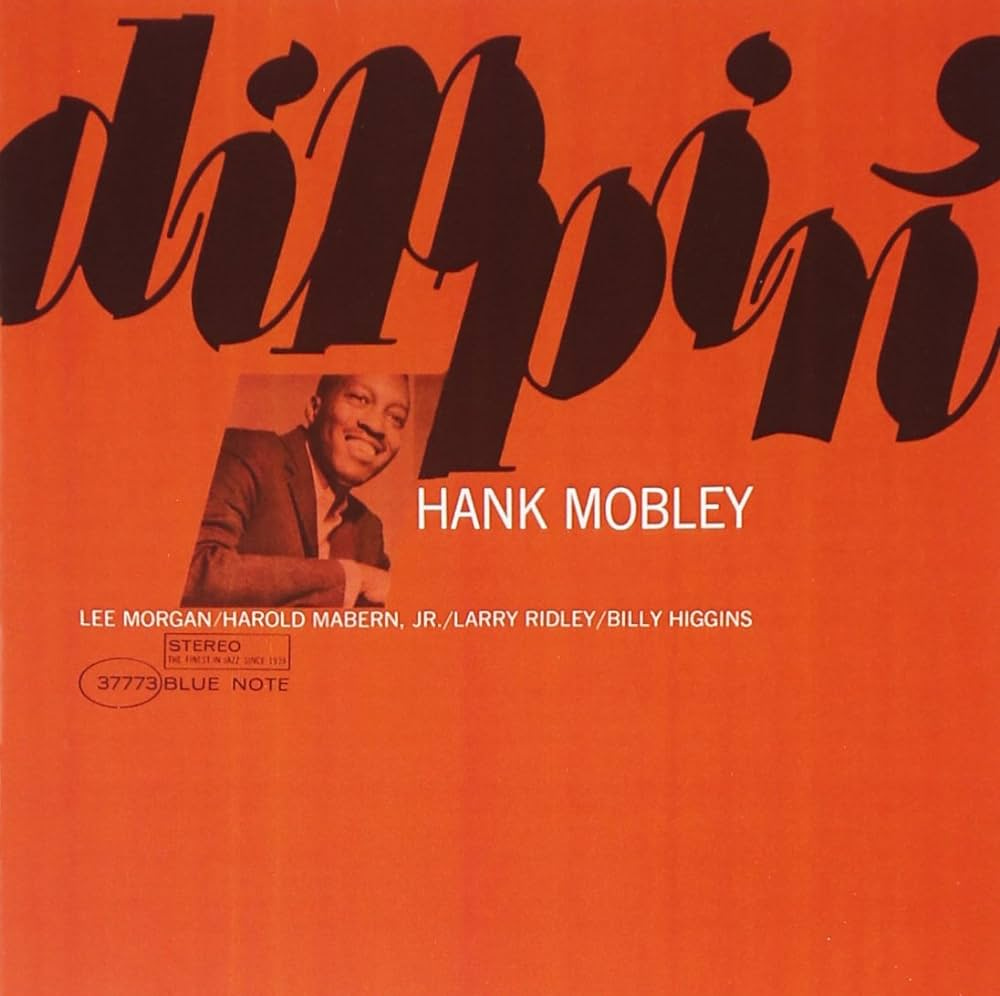

There were nine Morgan sessions with Hank Mobley. Morgan and Mobley are together for two of the other famous jazz Bossa Novas, “Recado Bossa Nova" on Mobley’s Dippin’ (recorded June 1965) and “Ceora” on Morgan’s Cornbread (recorded September 1965).

“Recado Bossa Nova" was composed by Djalma Ferreira with lyrics by Luiz Antonio. The original organ-heavy version from Ferreira in 1959 is not that syncopated, and frankly sounds more like bachelor pad music than anything else. (Not that there’s anything wrong with bachelor pad music.) The vocal hit in America was as “The Gift” on Eydie Gormé’s smash Blame It On the Bossa Nova, a version that is basically a chanteuse with lounge Bossa Nova accompaniment. (Not that there’s anything wrong with a chanteuse with lounge Bossa Nova accompaniment.)

Zoot Sims recorded Al Cohn’s arrangement of “Recado Bossa Nova" on an album of the same name in 1962, and that’s starting to foreshadow the Hank Mobley approach. Still, Mobley’s hard-bop-styled horn chart for Dippin’ nailed the assignment, and that heavily syncopated version with drum breaks has gone into repertoire as the way to play “Recado Bossa Nova." Killer track. (When I first got Dippin’ in high school, I listened to “Recado Bossa Nova" over and over.)

Billy Higgins offers something distinctive and powerful on “Recado Bossa Nova." At the top of the tune, he is playing a backbeat with a cross-stick alongside “timbale” tom fills. Amazing drumming! When I digitally slowed down the track to transcribe the melody, it turned out there was still a hint of a swung eighth-note in Higgins’s ride cymbal. Higgins didn’t change his strut no matter the genre: Swing, backbeat, bossa, the boogaloo of “The Sidewinder,” anything else. This is the highest level of mastery.

Due credit to Harold Mabern and Larry Ridley as well, they are all at this party together. Indeed, Mabern’s energetic and charismatic comping seems to have more Brazilian patterning than Higgins’s drumming.

Ridley and Higgins return for “Ceora” but Herbie Hancock is in the piano chair. Something about classic Bossa Nova seems to be relaxed, like water gently falling in the rain forest in the late afternoon. Well, Herbie Hancock gets it right, there’s no doubt about that. The opening piano chorus (and everything else Hancock plays on “Ceora”) is definitive. Compare Hancock with Tyner and Mabern in their solo choruses above; I’d describe the approach of Tyner and Mabern as more Cuban. (Mabern even plays some literal Cuban quotes in his “Recado Bossa Nova” solo.) Hancock is more Brazilian. Indeed, “Ceora” may be the most truly Brazilian feeling of the four tracks under consideration, especially since Billy Higgins returns to something like what Pete La Roca plays on "Blue Bossa" and "Recorda-Me," namely eighth-note brushes and clave cross-stick.

I learned “Ceora” as a teenager when in session with celebrated educator David Baker. Baker had his student combo at the Jamey Aebersold camp in Elmhurst read “Ceora” down in the original key in A-flat — before making us all play it up a half-step in A. That was a truly great lesson.

Recently one of my students at NEC brought in “Ceora,” and of course I made him play though it in A major. (Thanks, David Baker.) While working on the piece with my student was I struck by how deep Morgan’s composition really is: A motive is teased out through many keys, and the concluding few bars exhibit true melodic inspiration.

Naturally, the way Morgan and Mobley play the melodies of both “Recado Bossa Nova" and “Ceora” together is a masterclass in unison phrasing.

Whether Cuban, Brazilian, or anything else, it seems like many of the even-eighth note feels that were added to swinging jazz came straight from the dance floor and hit radio. It was a very impure situation, where commerce and art rubbed along in an agreeable fashion.

The rock shuffle might have had a similar process.

Jazz swings, obviously, but the swinging shuffle is a bit more of a specialized technique. The original shuffle was probably boogie woogie piano and droning blues guitar, followed by an evolution from the big band swing era (including Duke Ellington train evocations) into rhythm and blues. People like Louis Jordan, Lucky Millinder and Lionel Hampton are in this conversation, and the shuffle is all over the Chess blues records out of Chicago in the ‘50s. This style stayed in the jazz lexicon especially thanks to the work of Art Blakey and his Jazz Messengers on famous pieces like “Moanin’” by Bobby Timmons or “Blues March” by Benny Golson. (It’s impossible to imagine a Jazz Messengers gig without a shuffle in the set list.)

In the ‘60s, the British Invasion brought the “rock shuffle” into the mix. The English cats heard the Chess records and did their own thing. I can’t tell you exactly what’s different, but I know it when I hear it. “Revolution” by the Beatles is a famous rock shuffle.

Miles Davis hired Art Blakey for some exquisite records, but Miles Davis is not associated with the Jazz Messengers shuffle. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine Miles sitting in on “Moanin’” or “Blues March.”

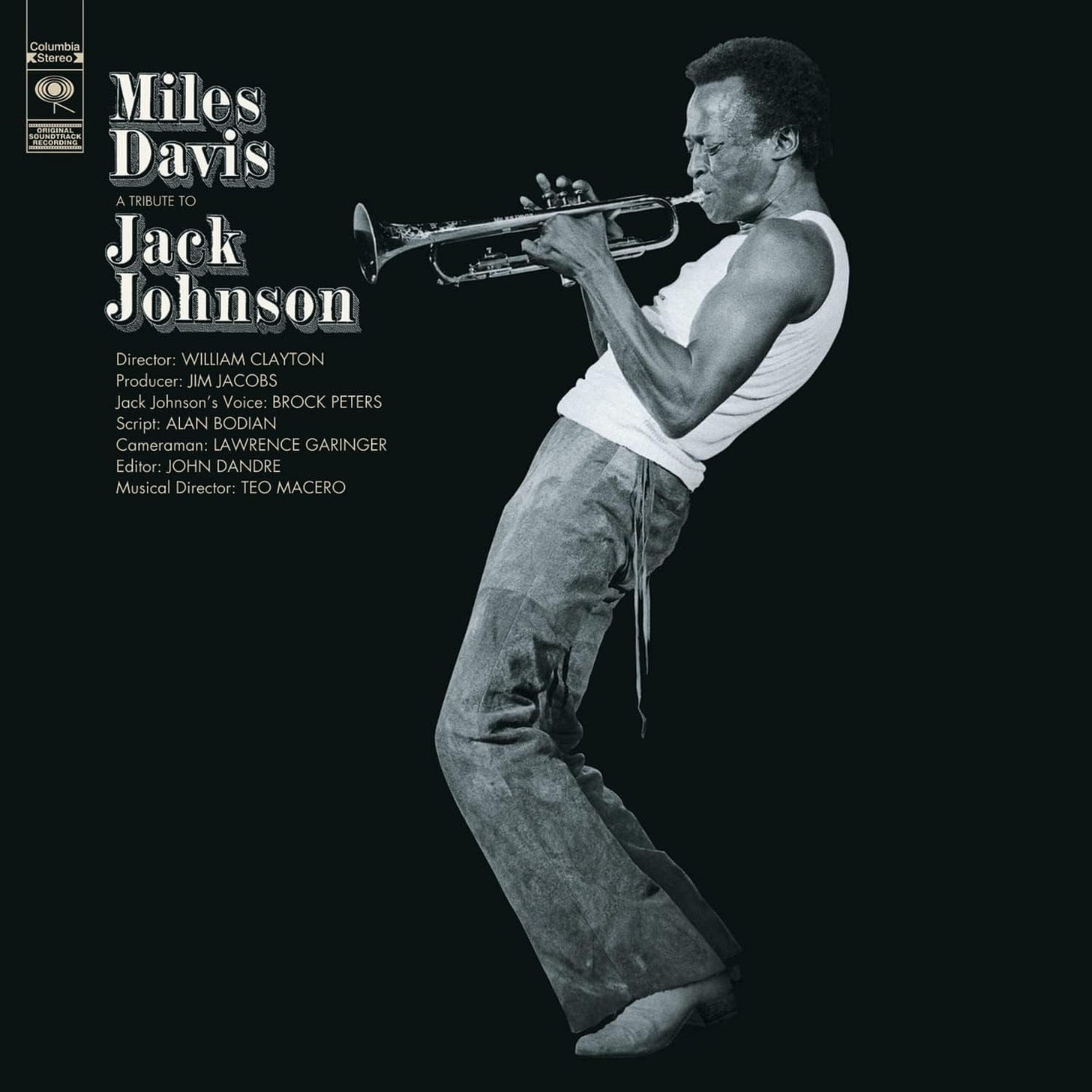

The first full on Miles Davis shuffle on record was tracked in 1970, “Right Off” on Tribute to Jack Johnson. Billy Cobham is playing a rock shuffle on this track, and he’s playing the hell out of it, too. Michael Henderson is on electric bass and there’s even a British guitarist, John McLaughlin. It’s a serious vibe from this rhythm team and right out of the gate, Miles lets loose with one of his most electrifying and technically fearsome trumpet solos.

Coda: Tony Williams

One of the people with their ear closest to the ground on these topics was Tony Williams.

Tony was all of 17 on Kenny Dorham’s Una Mas, playing a nice Bossa Nova with sticks.

Several tracks with Miles Davis and Tony Williams were vastly influential on how these rhythms were interpreted by the jazz world at large: On “Eighty One” from E.S.P. there’s something of a Bossa feel, and Herbie Hancock said he found the rhythm of “Maiden Voyage” on that take of “Eighty One.” (“Maiden Voyage” is not a Bossa, of course, but it is unthinkable without a Brazilian influence.)

“Freedom Jazz Dance” from Miles Smiles is unique, with a drum part that embraces rock ‘n roll know-how. However the place to hear Tony play a proper rock shuffle is “Going Far” on The Joy Of Flying.

When Tony tracked Jobim’s “Wave” with McCoy Tyner and Ron Carter on Supertrios, the drum part was a full roar of untrammeled creativity.

Thanks to Vinnie Sperrazza, Mark Stryker, and Darcy James Argue for help with this post. On Twitter, Peter LeCasse reminded me of Dorham’s “Una Mas.”

Thank you for mentioning and transcribing "Recado Bossa Nova". A killer track indeed. Not to get overly subjective, but as a listener even with the helpful and accurate articulation and phrasing markings in the transcription it seems easier to process the information while counting in 2/4.. As most Brazillian composers and players write and count Sambas and Bossa Novas (and certainly choros) in 2/4 it makes sense that the composer of this song most likely originally wrote it in 2/4. The first track on the record, Hank Mobley's composition, "The Dip" does "make more sense" to count in 4 (it's still a "swingin Bossa Nova" but there is enough of a pop and r&b sensibility that seem to place it safely in 4/4). Whatever the case (2 and/or 4), the cats on this record are swinging at 1000% and obviously well understood the undulating message of this exiting new music.

May I continue to make a case for the merits of 2/4 for anyone still reading:

2 is a very natural rhythmic unit biologically (2 legs, 2 halves of the body.)

2 is a great point of departure for understanding the feeling of Brazilian music and rhythms. There is often an intuitive (albeit ever-precise) anticipation of 1 and a more grounded landing (usually heard w/ the bass drum) roundly on 2 that give the music that soulful feeling of "lift".

2/4 and its inherent sixteenth note units of syncopation characteristic of Bossa Nova, Samba, and Choro probably make it easier and more precise for the intellectual center to process and comprehend that information in the long run. A vocabulary of "forks" (sixteenth and eighths in sequence) and ties develop into a language that creates more coherent pictures than you might get notating this music in 4/4. The extra "line" on the eight note somehow "anchors" the rhythms on the page, it really "ties the room together" and there's still plenty of space for triplets to create beautiful phrases and undulations.

I don't know, sometimes you say to a "jazzer": "okay, you want to play a Bossa Nova, that means we're in 2/4 now." -- and you get a blank stare even in 2024, eight decades later (--Bossa Nova originated in the 40s as a kind of slower samba with a sophisticated harmonic structure). The great early 60s recording of "Getz/Gilberto" is an absolute masterpiece, and there's so much Brazillian music like this that is well notated and readily available (e.g., jobim.org has thousands of original scores that provide alot of horizontal and vertical answers for us... The mid-century piano arrangements alone are works of art!)

In conclusion, thank you, Rhythmic Crusade accomplished.

Great article! In his own liner notes to Double Rainbow, Henderson provides some of the history of "Recorda-Me":

"The first tune I ever wrote, as a teenager, was the tune that I later titled 'Recorda-Me.' This was before the bossa nova was introduced to North America by Stan Getz and Charlie Byrd. My tune had a kind of generic Latin beat to it, without being any specific rhythm, like a pachanga or a bolero or a samba. But when I first heard this 'bossa nova' (above the gunshots, because I was in military training at the time), it caused me to go back to 'Recorda-Me', not to rewrite it - but to change the rhythm of the melody line, in order to fit the bossa nova pulse. So Jobim had a profound effect on even the way that I proceeded with melodies that I already had going on in my brain. I'll be forever indebted to him for that, and I had the chance to tell him so in 1993, when I was in Rio to take part in a tribute to him."