I’m participating on a panel about Charles Ives this week, which is giving me a chance to organize my thoughts about this crucial American composer.

17 tracks from the 20th-century American jazz canon that might relate to Charles Ives

Sun Ra, “Springtime in Chicago” from Super-Sonic Jazz (1956) A kind of “society” or “sweet” band tune with uncomfortable decoration. Many of the Ives 114 Songs are also sweet tunes with uncomfortable decoration. In this case, the topic is not yet quotation: Sun Ra wrote his original saccharine piece, all of the 114 Songs are original as well. Still, the works take on something far more esoteric in the final discombobulated arrangements.

George Russell, “You Are My Sunshine” from The Outer View (1962) This substantial arrangement of a famous melody includes the Ives tropes of polytonality and simultaneous tempi. Against the madness, Sheila Jordan sings the tune fairly “straight.”

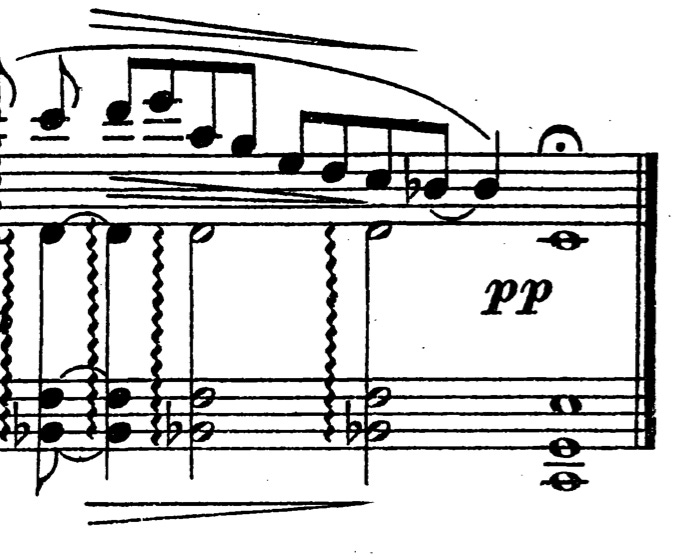

Albert Ayler, “The Truth is Marching In” from The Greenwich Village Concerts (1966) Ayler’s ensemble includes trumpet, violin, and cello. The churchy sound seems very primitive, like a Salvation Army band, the kind of band Ives references in “General William Booth Enters Into Heaven.” In a 1970 interview with Swing Journal, Ayler talks about Ives being one the most “beautiful” of composers, and is excited that a recent concert of Ives required not one but two conductors.

Keith Jarrett, “Moving Soon” from Somewhere Before (1968) Jarrett told me, “I went through a long Charles Ives phase, and gained a lot from him. The first time hearing him is revelatory, of course.”

There’s a mixture of harsh atonality and hymn in the head of “Moving Soon,” and that’s like Ives, but truthfully I hear little of Ives in most of Jarrett’s output. However, the pianist has repeatedly cited Ives as an inspiration to get away from it all, live outside the scene, and work on his music in seclusion.

Update, after the panel: We listened to “The Alcotts” played by Ives, and I suddenly felt that the final cadence — the lydian melody on B-flat resolving to C — was totally “just like Keith Jarrett.”

In discussion, it turned out that Paul Motian gave Bill Frisell the sheet music to “The Alcotts” and asked Bill to learn it on guitar. That didn’t happen, but perhaps there is some sort of Jarrett/Motian/”Alcotts” lineage which is more than a notion.

Charlie Haden/Carla Bley, “Circus ’68 ’69” followed by “We Shall Overcome” from Liberation Music Orchestra (1969) Chaotic layering of genres resolves into grand melody statement. In the liner notes, Haden describes a thoroughly Ivesian scenario:

The idea for "Circus '68, '69" came to me one night while watching the Democratic National Convention on television in the summer of 1968. After the minority plank on Vietnam was defeated in a vote taken on the convention floor, the California and New York delegates spontaneously began to sing “We Shall Overcome” in protest. Unable to gain control of the floor, the rostrum instructed the convention orchestra to drown out the singing. "You're a grand old flag" and "Happy days are here again,” could then be heard trying to stifle “We Shall Overcome.” To me, this told the story, in music, of what was happening in our country politically. Thus, in "Circus" we divided the orchestra into two separate bands in an attempt to recreate what happened on the convention floor.

Ornette Coleman, ”Broken Shadows” from Crisis (1969) A big tune is heard over and over again as the horns and drums go wild. What is more Ivesian than that? As a bonus, the drummer is the very young and unprofessional Denardo Coleman, who gives the music the “enthusiastic amateur” quality so prized by Ives.

Yusef Lateef, “Hey Jude” from The Gentle Giant (1970) Do not adjust your stereo: the music does a long fade-in. Lateef wails the familiar melody on oboe; the chaotic collection of choir, chimes, guitars, and drums in accompaniment is worthy of Charles Ives.

Weather Report, “Second Sunday in August” from I Sing the Body Electric (1971) Much early Weather Report with a “collective” ethos can be rather Ivesian. I chose Joe Zawinul’s piece “Second Sunday” for the symphonic-sounding timpani.

Charles Mingus, “Adagio ma non Troppo” from Let My Children Hear Music (1972) A full orchestra burps and chortles. The uncompromising mash-up of harmonic languages from romantic to dissonant is somewhat like Ives, as is the manner in which diverse instruments chatter on vamps.

Steve Lacy and Roswell Rudd, “Robes” from Trickles (1976) Sensational record of bluesy free improvisation. What gives “Robes” true Ivesian transcendence is a slow chimes part overdubbed by Rudd.

Anthony Braxton, “22-M (Opus 58)” from Creative Orchestra Music 1976 (1976) The AACM-school produced many march-type pieces where John Philip Sousa goes awry. Braxton’s take from his important big band record is definitive; at the time it was also a real shock. Trivia: playing bass drum on this track is Frederic Rzewski, the noted composer-pianist whose use of mash-up and quotation can be seen as belonging to the Ives tradition.

Carla Bley, “Spangled Banner Minor and Other Patriotic Songs” from European Tour 1977 (1977) Sophisticated collection of quotations, marches and mash-ups. Possibly the most Ivesian of all these selections, also because Bley also has a surreal but steady hand on the tiller for a substantial duration.

Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays, "As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls" from As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls (1980) This long suite celebrating Americana starts with crowd noise that the keyboard has to surmount, a theatrical effect that is in the Ives tradition. Lyle Mays said of this album: “One of the devices that film makers have available to them is the juxtaposition of opposite elements to achieve more nuanced and complex results.” This Mays quote also perfectly describes what we mean when we call something “Ivesian."

Later, for the First Circle tour, the Pat Metheny Group would enter the stage playing “Forward March” like an amateur marching band.

The Art Ensemble of Chicago with Roscoe Mitchell, “Walking in the Moonlight” from The Third Decade (1984) This sentimental ballad was written by the father of Roscoe Mitchell. While Ives surely would have appreciated the sentimental ballad on its own, there’s a truly Ivesian bonus: the horns are (intentionally) out of tune to the point that they recall the Three Quarter-Tone Pieces. An “a-wooga” bike horn goes off once in a while, Ives would have liked that as well.

Peter Erskine with Kenny Werner, “In Your Own Sweet Way” from Sweet Soul (1991) All sorts of the greatest jazz masters like Charlie Parker, Dexter Gordon and Sonny Rollins use quotation, but rarely do their quotations take over the texture of the music. On this track, pianist Werner peppers his solo with a steady stream of familiar melodies, some which are frankly ridiculous (like the James Bond theme). The result is about as close to Ives’s Symphony no. 3 as a straight-ahead piano trio could get.

Bill Frisell, two excerpts from “The ‘Saint-Gaudens’ In Boston Common” from Have a Little Faith (1992) The guitarist literally plays Ives on an album that surveys American music from Aaron Copland to Sonny Rollins to Madonna. The first short excerpt is just an unfriendly hello, dense and evocative, while the second longer excerpt takes Ives’s bluesy bass line in E for a creative improvisation from clarinetist Don Byron.

John Zorn with Naked City, “The Cage” from Grand Guignol (1992) After a free intro, the band does the song reasonably straight with Bob Dorough supplying the vocal.

—-

Widening the frame, all sorts of European jazz might have Ives references, from Django Bates to the ICP orchestra.

In 21st-century America, both Kneebody and Matt Moran’s Sideshow have done albums of Ives songs with Theo Bleckmann; Jamie Baum has written a substantial Ives Suite for septet; Bill Carrothers’s concept albums concerning war like Armistice 1918 are obviously indebted to Charles Ives.

My esteemed fellow “Charles Ives and Jazz” panelists include Jack Cooper, who arranged a full album of Ives for jazz orchestra on Mists and Eric Hofbauer, who amplified Three Places in New England for Prehistoric Jazz, Vol. 3.

There must be many more.

Ethan, these connections are wonderfully observed and will freshen my ears for a new listening excursion. I’m not concerned about direct historical connections since at my age I’ve absorbed enough of them and try to experience all of my music in the moment, where connections are immediate. Well done as usual, and thanks!

What is the conference that features this panel?