The discography divides neatly into periods sorted by record label: Blue Note, Prestige, Riverside, Columbia, and Black Lion.

A few specialty items not on one of these labels are also indispensable.

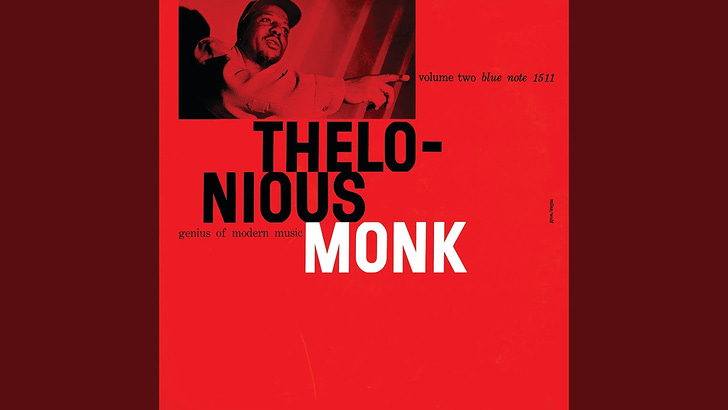

BLUE NOTE (1947, 1951-1952)

Lorraine Gordon, the late owner of the Village Vanguard, fell in love with Thelonious Monk’s music in the late 1940s and encouraged her husband, Alfred Lion of Blue Note records, to give Monk his first record deal. Lorraine appreciated how there was a palpable connection to the swing era in Monk’s modern sound; she also gave Monk the sobriquet, “The High Priest.”

Monk’s first short studio tracks as a leader include at least one bonafide masterpiece, a surreal arrangement of the old chestnut “Carolina Moon.”

However, the early Blue Notes generally have the weakest performances in the Monk canon. While not all the horn players are that good, everybody gets solo time. Some of the hardest Monk tunes like “Skippy” and “Hornin’ In” are from this era, and several of them would never return in Monk’s book. A couple of tracks with the piano in the midst of horns like a concerto such as “‘Round Midnight” and “Thelonious” remain compelling and unique to the first era. Standards with marvelous Art Blakey include “April in Paris” and “Nice Work if You Can Get It,” where Monk shows off a lot of chops.

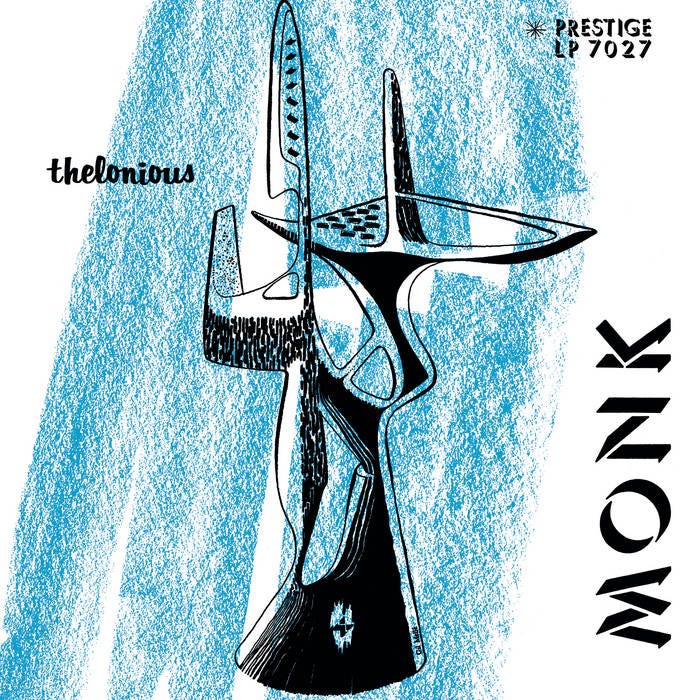

PRESTIGE (1952-1954)

Not quite LPs yet, the Prestige tracks produced by Bob Weinstock were 78s or collected on 10-inch before varied repackaging. The issues remain a bit confusing.

A particular favorite is 12-inch LP Trio with Gary Mapp and either Max Roach or Art Blakey in late 1952 and “Blue Monk” with Percy Heath and Blakey from 1954. Sometimes the piano is really out of tune but that tintinnabulation works just fine for the High Priest, who plays superbly on some of his best compositions and a profound unaccompanied “Just a Gigolo.”

Percy Heath turns the time around in his bass solo on “Blue Monk.” Monk ignores the mistake, keeps counting accurately, and wrong-foots the rhythm section on the head out. A small detail that says something about something but I have no idea what. Max Roach on “Bemsha Swing” is impossibly great: Among other details, he bangs a top cymbal exactly once. But who is playing out-of-tempo claves on “Bye-ya?”

Bassist Gary Mapp is on no other recordings. Apparently he was a policeman first and bassist second, and occasionally he plays exceptionally wrong notes. But, warts and all, the final product is simply transcendent.

Other Prestige albums feature more experienced soloists than those heard on the Blue Notes. Sonny Rollins is superlative on his chorus during “Let’s Call This.” There’s a picture of Rollins with Monk and Roy Haynes at the Five Spot a few years later. If only one of those nights had been recorded!

Julius Watkins gets a star turn on french horn, that’s fun. The tracks with Frank Foster and Ray Copeland are also good, especially “Hackensack” with unruly Curly Russell and Art Blakey.

The most famous Prestige session is Christmas Eve 1954 with Miles Davis and Milt Jackson. If you haven’t dealt with that piece of jazz lore and legend, stop reading this page and go listen to the two takes of “Bag’s Groove.” Monk doesn’t comp behind Miles’s perfect melodic blues over dancing Percy Heath and Kenny Clarke. After bringing in the avant heat behind effusive Milt Jackson, Monk gets his own astonishing choruses. “Spring Swing” and two takes of “The Man I Love” are also essential.

RIVERSIDE (1955—1961)

Monk recorded extensively for Orrin Keepnews, who eventually produced a major box set, The Complete Riverside Recordings.

Keepnews’s notes to the set are informative but also distractingly egotistical. Still, in terms of sheer number of hours of superb and diverse music, the Riverside era triumphs. This notably strong sequence starts with two special projects suggested by Keepnews.

Plays Duke Ellington. Monk plays Ellington must be about the first and still one of the best examples of a concept album. The gait between Monk, Pettiford, and Clarke is spectacular. Monk’s touch is more delicate than usual here, and Clarke whispers along on brushes. Each track is beautiful in its own way, I’m always struck by something new.

The Unique Thelonious Monk. Perhaps not as rarefied as the Duke album but still essential. The opening “Liza” is Monk at his most explosive. “Just You, Just Me” has a nifty arrangement. “Tea for Two” is harmonized with the progression from “Skippy.” The full-arm black key cluster after white key chords on “You Are Too Beautiful” is pure Thelonious.

Brilliant Corners. A famous session that is a bit rough around the edges. Sonny Rollins is masterful but the rest of the band has trouble nailing every detail. The addition of celeste on “Pannonica” and tympani on “Bemsha Swing” is confusing, while the many edits on the title track are distractingly obvious. Not sure if the rhythm section of Pettiford and Roach are on always on the same page for the very long “Ba-lue Bolivar Ba-lues-Are.” There’s one undisputed highlight, a solo piano “I Surrender Dear.”

Thelonious Himself. “I Should Care” is quite deconstructed, while the blues “Functional” was compared to James P. Johnson by Monk himself. Eventually, John Coltrane and Wilbur Ware show up for a rhapsodic rendition of “Monk’s Mood.” Monk’s connection to European classical music should not be overemphasized, but this rubato, drummerless, cadenza-filled “Monk’s Mood” seems to be a response to modernist European chamber music. (Tellingly, when Monk played Carnegie Hall with Coltrane, he began the set with this arrangement.)

Monk’s Music. The blank-faced hymn “Abide with Me” confirms Monk’s relationship to both church music and four-part chorale writing. It also satisfies Keepnews’s request for a “new Monk tune,” for the piece is by the 19th-century Englishman William Henry Monk and found in the Book of Common Prayer. (The four horns read the four parts from the hymnal.)

Coleman Hawkins was an early Monk supporter, and a quartet “Ruby My Dear” shows how well he understood the romantic side of the composer. After Hawkins died, Monk played this recording “Ruby My Dear” over and over for days.

Wilbur Ware, one of very greatest bassists by any standard, barely plays a single correct note on “Ruby My Dear.” In general Ware and Art Blakey seem a bit perplexed by the music on the date. The full band performances are very long and filled with mistakes, “Epistrophy” is particularly hard to listen to. However, certain details are fascinating, like Ware’s smart harmonic analysis of “Well, You Needn’t” (he adds an E-flat chord to the fourth bar of the A sections) and Blakey’s blurring of tempo on “Crepuscule with Nellie.”

Mulligan Meets Monk. Gerry Mulligan was a great connector in this era, recording meetings with all sorts of cool cats from Johnny Hodges to Paul Desmond. (Both of those discs are beautiful.) Mulligan Meets Monk is the only Monk album where a horn player offers counterpoint on the melodies and backgrounds to the piano solos. Sometimes it just seems like noodling, but other times it works fairly well, especially the nice breathy baritone half-notes and mild syncopations during Monk’s improvisations. Mulligan is swinging and Ware and Shadow Wilson are in their element. Overall quite strong, but the one-off quartets with Gigi Gryce or Clark Terry have even more to offer.

Thelonious in Action and Misterioso. This is the second Five Spot quartet, Johnny Griffin took Coltrane’s place. Griffin is one of the great virtuoso pleasures of jazz, but he’s not perfect for Monk. Coltrane could also play a million fast notes but they somehow sat inside Monk’s piano comping. Griffin is just blazing away on top. Roy Haynes is the real star of the these live performances, although he should be louder in the mix. Ahmed Abdul-Malik’s own albums are a surprisingly successful blend of East meets West, but for me he plays better at Carnegie Hall with old-school swinger Shadow Wilson than at the Five Spot with burning Roy Haynes. Still, these two albums are undeniable jazz classics, and for many were a gateway into digging the High Priest. I’m complaining about Griffin but he’s still a hell of thing here, especially when eating up rhythm changes on “Rhythm-a-ning.”

Clark Terry: In Orbit. Two Riverside stars meet in this provocative and engaging album. It would be one thing if Terry had played a bunch of Monk tunes or repertoire specially tailored for the date. Instead the set list is essentially what Terry would play with anybody. The highlight is “Let’s Cool One” with phenomenal Philly Joe Jones.

The Thelonious Monk Orchestra at Town Hall. The debut of magnificent Charlie Rouse in the Monk band! It’s not that Rouse plays all that “motivic” or “abstract”: He doesn’t. Charlie Rouse is a straight-ahead master. Full stop. But Rouse’s non-avant lines somehow interface correctly with Monk’s wild comping and general aesthetic.

On the full band pieces, Hall Overton transcribed Monk’s voicings accurately, orchestrated the piano solo on “Little Rootie Tootie,” but doesn’t do much else. It’s a classic record with a few star soloists getting a rare chance to sing out with Monk — Pepper Adams sounds wonderful on “Rootie Tootie” — but the later gig Big Band and Quartet in Concert has a little more of Overton’s own interesting imagination in evidence.

Five by Monk by Five. Sam Jones and Art Taylor are heard both at Town Hall and this quintet date. They are excellent but not as perfect for Monk as the future rhythm sections with less famous players: John Ore, Butch Warren, Larry Gales, Frankie Dunlop, Ben Riley. It’s a thrill to hear Thad Jones with Monk but — in perhaps a minority opinion — this quintet date doesn’t fully gel into an outstandingly memorable confluence of energies. All the pieces are quite long. There is no obvious narrative drama in most of Monk’s small ensemble music, it stays pretty much the same dynamic at all times, so when there is more than one horn the pieces have the potential to extend to unwelcome lengths. The coolest track might be the fastest, “Jackie-ing,” which is so beautiful and so strange and puts Thad Jones’s imagination into high gear.

Alone in San Francisco. This might be Monk’s nicest piano in an American studio recording. “Pannonica” gets for me the definitive reading, ruminative and swinging, with wonderful swirling arpeggios in the in final bridge. Another key track is Irving Berlin’s “Remember,” which begins with Monk playing the melody in the left hand under intentionally awkward chords. Then he swings out. This “Remember” was recorded four months before the classic version that opens Hank Mobley’s Soul Station.

Thelonious Monk at the Blackhawk. West Coast lions Harold Land and Joe Gordon sit in with Monk’s quartet. This live date has a nice vibe, although the crowd noise is extremely loud. It is Billy Higgins’s only recorded session with Monk. The phrase “lift the bandstand” is attributed to Monk, but for me no one can “lift” a group quite like Higgins. The drummer and the pianist radiate pure joy together.

John Ore is good too. Along with Butch Warren and Larry Gales, Ore is one of three excellent but comparatively unheralded Monk ’60s bassists who “got it.” Swing hard, don’t forget the pitches but don’t worry too much about them either. Just a little elegant, but not too much.

Two Hours of Thelonious (or Monk in France and Monk in Italy). Rouse and Ore were perfect. The group just needed a steady drummer, and they found him in Frankie Dunlop. Before Monk, Dunlop played with Maynard Ferguson, afterwards with Lionel Hampton.

For Modern Drummer, Dunlop talked about Monk and big band music (especially Jimmie Lunceford) in one of the most interesting interviews ever done by a Monk sideman. (The best parts of this interview can be found at Todd Bishop’s site.)

I remember one Monday night in the wintertime, Clark Terry had his big band up at The Baron. Monk ran out of the club and saw me. He said, "Hey Frank, I want you to sit in and play with Clark. Go in and swing one. Man, you can make that band swing like it's supposed to." Then Monk went back in and went up to the bandstand. He said, "Hey Clark!" Clark knew Monk. Clark said, "For those of you who are not aware, that's Thelonious Monk—The High Priest of Bop—over there hollering at me. What do you want?'' Monk said, "I was just outside talking to Jimmy Lunceford and his band. They want to sit in and play one. Is that alright with you?" That was the way Monk would give you a message. He was comical, but he had a message. He said very little, but what he did say made sense. It would make you laugh. He didn't want you to feel bad. He thought you'd get the message if he told you in a humorous way. He never even fired anyone. He used to say to me, "Frank, as long as you're swingin', man, I don't care what you do. You know what? On intermission, you can go out and kill a cat if you want to, as long as you swing when you come back and hit the stand with your drums." His point was that the main thing was to concentrate, swing, and play your instrument. He was giving Clark Terry a message that night at The Baron. He was saying, "Look, I've been listening to you guys up there. I've been in this place for a whole hour, and you cats aren't doing anything for my ears tonight. You cats aren't really making it."

There was something else that Dunlop had besides swing. Something a little surreal in the language. It’s not totally slick and level-headed. There’s a hint of clunky and disorganized, like a little kid beating on pots and pans.

Rouse isn’t so clunky but he’s not afraid of clunk, either. Ore clunks away beautifully. These are Monk musicians!

Orrin Keepnews is rather dismissive of these two European gigs in the big booklet that accompanies the Riverside box simply because he had nothing to do with producing them. However, these live quartets offer perfect jazz: modernist, bluesy, soulful, weird, and so damn swinging. The quartet is a “thing,” an organism that radiates correctly and naturally. The group is also audibly excited to be in Europe playing in superb concert halls to packed audiences that love and respect their music.

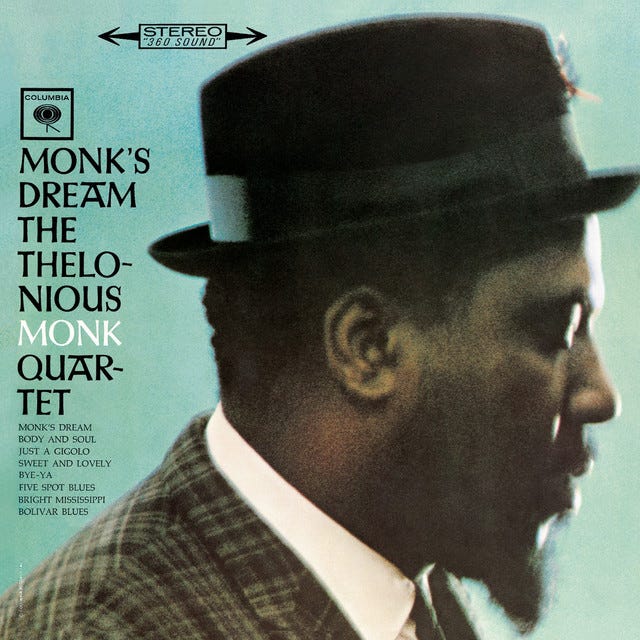

COLUMBIA (1962-1968)

Conventional wisdom says Monk’s big breakthrough to a major label also was time of retrenchment and ennui. Even though Monk’s quartet with Rouse was one of the great groups of all time, I concur, at least in terms of the studio records. There’s nothing really wrong about any of them, except perhaps occasionally the tracks run long with too many solos. Any one of them is still a good introduction into Monk, and they served that function beautifully.

It’s only when you compare the studio quartets to the live documents that the studio documents seem lackluster. Perhaps part of the problem is simply that the albums weren’t produced very well. Teo Macero is a crucial figure in jazz history, and Monk liked him enough to write the song, “Teo.” But the pianos aren’t always in tune and the sonorities aren’t always so well blended together. Compare a Monk record of this era to a Macero-produced Miles Davis album of the era: The Miles records generally sound much better, even though the engineers, studios, and pianos are the same.

The best Riverside records were partly the result of Keepnews staying in the ring with Monk, taking the blows, returning with a jab, and finally getting it done. For the first few years at Columbia, Macero just let Monk be. Monk seemed to like that better, but the catalog doesn’t show that Macero’s “hands off” approach automatically made better records. However, when Macero suddenly took the reins for the last record, the Oliver Nelson big-band Monk’s Blues, he ended up producing the one Monk album almost nobody likes. (Robin D.G. Kelley’s biography is highly informative about Monk’s final year or two at Columbia.)

Of the quartet studio records, Monk’s Dream still seems to be the freshest, with Dunlop’s drums exploding out of the speakers on the opening track.

There are good things on everything else from the Columbia studio quartet catalog, perhaps especially the standards, and the final Underground has a bevy of beautiful new tunes.

There are two non-quartet Columbia discs that rank as essential.

Big Band and Quartet in Concert. Overton is back as arranger and lets himself extend out into Monk’s world a bit more, although almost everything the horns plays is still based on a Monk piano part. Butch Warren is even better than John Ore, an eager swinger that creates a perfect “roar” downstairs with Dunlop. The new tune is “Oska T.,” which swirls obsessively in A-flat. It’s 1963, modal jazz was clearly here to stay, so Monk made sure to have a personal take on a long number based on one chord. Since there were no recordings of this tune yet, the creative backgrounds might indeed be entirely Overton’s invention. Martin Williams wrote up watching a rehearsal for DownBeat in an article that has some insight into the Overton-Monk dynamic. (At one point Overton auditions chords for Monk, Monk doesn’t say anything.) Main soloists Rouse, Thad Jones, and Phil Woods deliver the goods throughout the whole gig. For me this set is superior to Town Hall in almost every way.

Solo Monk. Monk touched on stride in his solo work before but “Dinah” couldn’t be more explicit. “Dinah’s” lyrics refer to “Carolina” – could that be another nod to James P. Johnson and Johnson’s famous stride test piece “Carolina Shout?” Great version of “Ask Me Now.” The whole album is thoughtful and loving, although if you put a gun to my head I might rank it the least of the five solo albums overall.

Although not released until after Monk stopped performing, two of the Columbia live quartets are two of my favorites.

Live in Tokyo. With Rouse, Warren, and Dunlop in a far foreign land. This is my favorite Monk working band in a well-recorded situation. One for repeat listening. “Straight No Chaser” my god. It’s just a bebop blues, but it is also a whole universe of stylish aesthetic choice.

Live at the It Club. The next rhythm team of Larry Gales and Ben Riley was also really great. Maybe more than anybody since Wilbur Ware, Gales could jump in and “comment” on Monk during the piano solos, for example on “Rhythm-a-ning.” Ben Riley was a deep swinger who would go on to be the most popular and frequently recorded musician of those who had a “mostly Monk” association during the ’60s. At the It Club, Gales and Riley were new to the gig but sound well up on what the music needed. Slightly out of tune piano, tough tenor, big swing, a rare “Gallop’s Gallop,” terrific date.

BLACK LION (1971)

Gerald Early’s essay “Thelonious Monk: Gothic Provincial” argues that Monk more or less declined after the 1940’s, and declares the reason for this decline to be institutional racism. In his biography of Monk, Robin D.G. Kelley suggests something similar, that Monk just got tired of the fight.

Whatever the case, there was a stunning last act during the Giants of Jazz tour in 1971. Monk recorded about two dozen trio and solo tracks in London for producer Alan Bates. The sound is bright, even glossy. This “European” engineering shouldn’t be so attractive but it works. If I put on my critic hat, I’m compelled to note that Al McKibbon is no John Ore, Butch Warren, or Larry Gales. Frankly I wish Monk and Art Blakey had recorded a few tracks duo. But when I take off that critic hat I’m just happy that any of this happened at all.

Occasionally you can hear Monk remembering how a song goes or getting lost in a detail. But, especially in the solo set, the tracks gain momentum as they go along. “My Melancholy Baby” is devastating.

THE REST OF MONK ON RECORD

Someone needs to collect all the 1941 Jerry Newman recordings from Minton’s for a well-produced set. For now, the two CDs Thelonious Monk: After Hours at Minton’s (Definitive) and Don Byas: Midnight at Minton’s (High Note) seem to have most of the tracks with Monk.

The music from Minton’s is fabulous listening. Herbie Nichols said he would rather listen to Monk play “Boston” than anybody else. “Boston” is easy stride-type oom-pah accompaniment divided between the hands. You hear “Boston” all over the Minton’s stuff, and sometimes Monk walks bass lines, too. It’s all very swinging. of course. It was the dawn of the new avant-garde music, bebop, but they were still swinging!

(In the Town Hall rehearsal tapes at Eugene Smith’s loft, there’s a duo of Phil Woods and Monk playing “Lady, be Good.” Monk plays full out rhythm guitar quarter notes, kind of like Erroll Garner, with a big accent on two and four. Very swinging.)

Monk’s first commercial recording was four tracks with Coleman Hawkins in 1944. These are really enjoyable, and Monk sounds like Monk.

Did Hawkins “get” Monk more than Charlie Parker or Dizzy Gillespie? Live tracks with Dizzy’s big band in the 1940’s have few obvious Monk moments, and Bird struggles with “Well You Needn’t” on a truncated live track. The 1950 studio Norman Granz session with Bird, Diz, Monk, Curly Russell, and Buddy Rich is an essential library item — but Monk barely gets to solo.

Much later, the 1971 “Giants of Jazz” package tour of Gillespie, Sonny Stitt and Kai Winding with Monk doesn’t coalesce into memorable music. Monk doesn’t solo much and frequently lays out.

A couple of bootleg solo tracks were recorded at Timme Rosenkrantz’s apartment in November 1946 and made available on Timmie’s Treasures. On a long “These Foolish Things” Monk is Monk, but not quite as resolutely idiosyncratic as he would become later. Indeed, the gorgeous improvised melodies in the middle recall the relaxed lyricism of Lester Young.

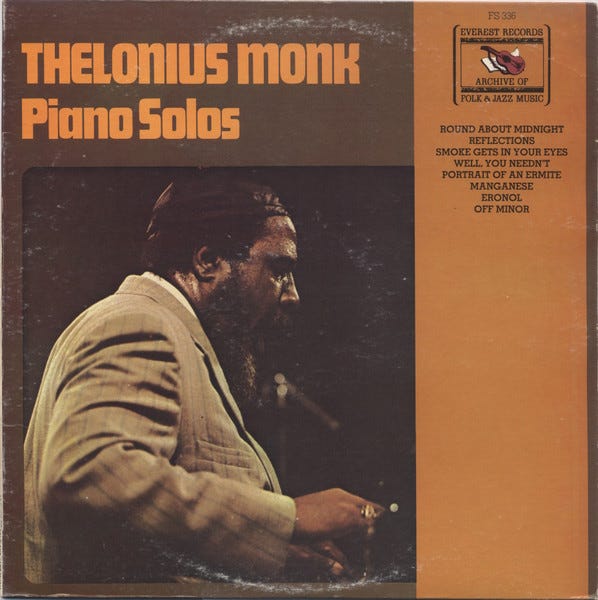

On his first trip overseas in 1954, Monk casually made an immortal masterpiece in a Parisian studio. Originally for Vogue, it has been issued under many names and labels. Mostly superb originals plus a magnificent “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.”

Gigi Gryce knew what he was doing when he brought Monk, Percy Heath, and Art Blakey together for half an LP on Signal in 1955. The three Monk tunes, “Shuffle Boil,” “Brake’s Sake,” and “Gallop’s Gallop,” might rank as finest Monk groupthink from a studio ensemble that wasn’t a working band.

Newport ’55 has three tracks with Miles, Zoot, Mulligan, Percy, and Connie Kay, including a famous “‘Round Midnight” that helped Miles begin his trek to superstardom.

(It is rather stunning to hear Miles play ‘Round Midnight” with the correct changes!)

Even better are four tracks from Newport ’58 with Henry Grimes and Roy Haynes. Grimes is very young but he throws down hard, with aggressive accompaniment and a strikingly brilliant solo on “Well, You Needn’t.” Haynes crackles and pops like always.

There are only three studio tracks of what by all accounts was one of the most exciting groups in history: the Five Spot quartet with Coltrane, Ware, and Wilson. “Trinkle Tinkle” is famous, but “Nutty” is where one just begins to sense what Ware might have brought to this group when it all was radiating correctly from tip to toe. (Coltrane talks about Ware quite a bit in his interviews.)

There are also two live dates with Coltrane that surfaced only recently. A Five Spot session with Abdul-Malik and tremendous Roy Haynes offers a Coltrane nearing the end of his tenure and playing with enchanting melodic freedom, but the fidelity is so atrocious that I hardly ever return to it. A much more enjoyable session was the much-heralded late night session at Carnegie Hall with Abdul-Malik and Shadow Wilson. There was so much hoopla about this date in the jazz press that I was slightly disappointed when I first got it. However, the fault was mine; now it just knocks me out, and is surely the best place to hear Coltrane’s fury (his “sheets of sound”) intertwine with Monk’s comping. A perfect match. Wilson is nice and loud in the mix.

In 1957 Sonny Rollins invited Monk and quintessential Blue Note artist Horace Silver to duo on a long “Misterioso” at Van Gelder’s. It’s a wonderful document but I’m not sure if Horace’s familiar and funky kind of statement comes off so well compared to Monk. On the quartet “Reflections” the intro is unlike anything else, and the whole performance has a deep emotional core.

On video there’s a fabulous “Blue Monk” with Abdul-Malik and Osie Johnson for the 1958 television show The Sound of Jazz. Count Basie is there, sitting right next to the piano.

Monk’ only association with Atlantic was on Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers with Thelonious Monk in 1958. Many adore this album, but I’ve always thought it lacked something. It is interesting to hear Monk play a slow minor blues by Johnny Griffin, “Purple Shades.”

The Monk estate put out a two-CD set of Monk practicing “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” on The Transformer. Listening to it in a straightforward fashion is like experiencing abstract European modernism.

A quartet of Rouse, Sam Jones, and Art Taylor can be heard in a good set at Newport ’59. The easiest Monk tunes and an unhampered festival setting bring out the best in the band. That quartet is sort of joined by Barney Wilen on the recently released movie soundtrack for Les liaisons dangereuses, a 2-CD set that is primarily of academic interest. (At one point Monk struggles to teach Art Taylor a drum part to “Light Blue.”)

Non-standard issues from the 1960s include a joyous set at the Village Gate with Rouse, Ore, and Dunlop, which might have the fastest Monk-led “Rhythm-a-ning” on record. After Rouse left the band he was replaced by Paul Jeffrey. Through Mike Kanan I heard Leroy Williams play a wonderful 1970 tape of Jeffrey, Wilbur Ware, and Leroy himself at a club in North Carolina. Jeffrey held it down and played great with Monk for about five years: big sound, melodic ideas, swinging hard. Players like Clifford Jordan and Sonny Rollins are somewhere not too far away from Jeffery’s conception.

There’s a lot of Monk captured in the 1960’s on video, both solo and quartet. A short all-Ellington concert with a fiercely striding “Satin Doll” is a minor miracle. All these beautiful videos are among the best ways to appreciate the whole Monk.

Back to the LPs: Does it make sense to make a top three? Probably not, but there’s never time to listen to everything. Here’s what I would take to that hypothetical desert island:

Trio (Prestige, 1952 and 1954, with Gary Mapp, Percy Heath, Roach and Blakey)

Solo (Paris, 1954)

Live in Tokyo (1963 with Rouse, Warren, Dunlop)

Much appreciated. It’s helpful in pointing out some things I’ve overlooked. I have loved almost everything I’ve ever heard (although I certainly haven’t heard everything), but agree that ‘Thelonious Monk Trio” is at or near the summit of a very high mountain.

Somewhat related, I just saw Sullivan Fortner play Monk at SFJAZZ in the small room there. Superb!!! Really brought out the stride in several numbers. It was a great performance. He brought me totally into Monk’s world, without playing everything like Monk did. The rhythms were there but the interpretations were fresh and utterly inspiring. All Monk except one Bud Powell tune, plus Cherokee. What a great musician and artist Sullivan is proving to be.

THANK YOU